3 Keys to Improving School Climate: How 1 ensures the other 2 succeed

School climate and social-emotional skills are on the front burner of school initiatives, as we strive to address the growing mental health issues of our youth. How many different school climate, SEL and mental health initiatives is your school implementing at the moment? If you’re like most weary educators, your answer is probably “too many.” Positive school climate programs and projects are worthwhile and require considerable time and effort. Yet, many of these initiatives are producing minimal gains. To ensure what you are doing is making a difference, it’s helpful to examine our goals, the initiatives we choose and consider how they intersect. To keep things simple, I suggest focusing on 3 key elements which help us accomplish 3 distinct but interdependent school climate goals. If these are achieved, you likely will be able to let go of many other overlapping initiatives.

Three Key Elements:

- Model, teach and practice social and emotional skills with all

- Help adults to develop intentionally positive communication

- Replace control-oriented, punitive and exclusionary discipline practices with collaborative, humane solutions.

When the whole staff works together to understand the purpose of these initiatives, it becomes quite easy to identify what might need to change in our school. The most important characteristic for any person, place, policy, program or process in a supportive school is whether they are perceived by our stakeholders as “doing school with me” or “doing school to me.” That seems to make the difference between something people will eagerly support and something people object to and avoid doing.

As a first step, let’s examine what each of these school climate elements means. If you polled every adult that works in your school, you’ll likely get a wide variety of answers. Let’s begin with what I have found to be the least understood:

1 Model, teach and practice social and emotional learning skills with students

The term “SEL” is often attached to anything and everything that schools try to do that is positive. The reason not much is accomplished, is that SEL is not that. SEL refers to teaching social and emotional SKILLS in a sequential, developmental order, every year, to every student, in every grade. Just like learning to read and write, there are specific behavioral skills that help us deal positively with the social and emotional challenges in our daily lives. So, an SEL activity is not about “preaching” about qualities of character nor telling inspiring stories.

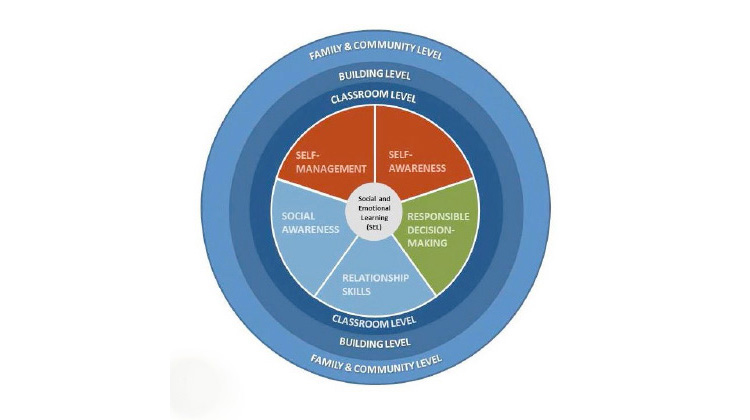

Rather, SEL means modeling, teaching, practicing and applying specific behaviors that will help us reflect on and choose beneficial words and actions, which leads us to develop those desirable qualities of character. Most importantly, SEL does not point out what people are doing wrong. It is a strength-based approach that helps children see their own and other’s unique strengths and value. It begins with developing a positive self-concept by learning to recognize our natural strengths, identify our emotions, develop a sense of self-confidence, etc. These self-awareness skills are followed by self-management, social awareness, relationship, and then, decision- making skills. (See CASEL SEL Competency Chart in this Dropbox folder: http://bit.ly/3KeysSC2020).

Each SEL skill builds upon the one that came before, so the order in which they are introduced matters greatly. For example, we are not really ready to make good decisions until we have developed the personal and social skills that come before. So, starting the school year with an assembly program about not bullying others or doing drugs has little impact.

In SEL lessons, life’s challenges are discussed, and proactive skills to address them are practiced and applied in other settings, in order to develop that behavioral skill. There is no preaching about how you “should” behave. For example, to help students ask for what they need without creating a defensive reaction, they learn to state their feelings, why the action of another is causing the feeling (without using words that blame or judge), and then suggest an alternative, helpful behavior. This skill is practiced using scenarios in class and at home.

An SEL program is optimistic, caring, and respectful as it builds trusting, dependable relationships in our classrooms between the teacher and his or her students, as well as between the students. Strong programs have family connection activities to help parents understand the skills and encourage them to model and practice them with their children and other family members. This improves communication and relationships at home.

If you apply this definition of SEL to the experiences you are currently providing, you can determine which ones are teaching and practicing specific competencies and which are pretty much preaching about what we wish for or expect from our students. It’s not that qualities of character are less important. Quite the contrary, providing students with specific social and emotional skills helps them to develop these qualities of character.

2 Help adults to develop intentionally positive communication skills

When we examine the 27 SEL competencies that we wish to teach our children, it becomes apparent that many of these positive behaviors are not modeled consistently by our school adults. Actually, we should not be surprised. Most of us have never been taught these skills directly. Some of us were lucky enough to have grown up in caring families and classrooms where adults consistently modeled some of these positive behaviors, yet they likely were never labeled for us. We simply copied the models we observed – the good and the not so good.

Most classroom teachers and school leaders will admit that intentionally positive, empathic communication skills were never discussed in any higher education degree program they completed. We have left our teachers and school leaders to fend for themselves to find ways of communicating that work for them. The result is a lot of inconsistent behavior by the adults in our schools. As pressures mount we are often triggered by strong emotions ourselves, and then react literally without thinking, instead of calming down first, in order to respond more thoughtfully. Few school adults have learned about what makes people choose their behaviors or more importantly, that everything we say and do messages others that we believe they are able, valuable and responsible, or that they are not. Some educators believe students will choose beneficial behaviors when they have the skills to do so. Others believe some students purposely defy rules and expectations, so punitive consequences must be in place and used consistently.

Dan Siegel’s valuable work in explaining interpersonal neurobiology to teachers, parents and children sheds new light on why people do what they do. His simple Hand Model of the Brain videos and books for parents and educators (see Dropbox Folder) help people of all ages understand how strong emotional triggers make it impossible for us to access the thinking part of our brain (prefrontal cortex) when we feel threatened. He encourages us to recognize that when a person won’t respond appropriately, it might likely be because at that moment, they actually can’t and need time to let the emotion subside before they can reflect thoughtfully on what happened.

Adults as well as children can be triggered by a frustrating or threatening situation. At that moment, the amygdala (the downstairs or primal part of the brain) takes over to protect us and as the emotions escalate, it literally disengages from the prefrontal cortex (upstairs or thinking part of our brain) making it impossible to make a beneficial choice. Dan Siegel calls this “flipping our lid.” Until we calm down, the upstairs part of our brain is not able to message the downstairs part of our brain, so we literally react without thinking and choose to fight, flee or freeze.

Mindful and empathic communication skills are an essential part of developing trusting, respectful relationships with others. You don’t have to be a psychologist to develop these skills. When we learn how to listen for feelings and needs, strive to understand the perspective of others and then express our own needs without blame or judgment, our communication skills become the most powerful change agent in our school.

Likely, your school has not yet developed a “communication code” for its staff. This is possible when people begin to use positive communication skills and find success with them. We work on taking the perspective of others and realize that we are not in charge of the meaning of the messages we communicate. The person receiving our message is responsible for giving it meaning, so we need to carefully examine their verbal and non-verbal clues to determine how it was received. We consider their needs and not just our own, when we communicate empathically.

It is unreasonable to expect everyone to suddenly change the way they communicate. However, when we explore new ways together, staff members (and parents) discover that they don’t need controls to “get someone to do something.” Their needs and the needs of those they work with are met respectfully – simply because we’ve learned how to listen for the other person’s feelings and needs, and reflect on our own. We discover a new way of interacting with others and our personal and professional relationships improve. I’ve noticed that when someone has success applying these skills to challenges in their personal lives, they are eager to use it consistently in their professional lives. (See Positive Communication resources to learn more.)

3 Replace control-oriented, punitive and exclusionary discipline practices with collaborative, humane solutions

During recent years, the response to children choosing challenging, disruptive or hurtful behaviors has been to identify long lists of escalating consequences, punishments or exclusionary practices like detention, time-out, and in-school or out of school suspensions. These approaches are intended to teach someone a lesson, remove them from the environment they disrupted, and protect the others in the school. A collaborative and optimistic approach to addressing inappropriate behavior starts with the premise that people want to be accepted, connect and do better – if only they knew how. They don’t have these skills, so they’ve learned to use what works for them to defend their feelings or avoid things they can’t do well. Often, their brains become “wired” to react strongly to emotional triggers that they have not yet learned to manage.

So, helping school adults to respond with curiosity and thoughtfulness when a student, parent or colleague says or does something that upsets them, is one of the most useful SEL skills we can use in our personal and professional relationships. When a school develops a collaborative, proactive approach to inappropriate behavior, we see skillful adults whose first response is to be curious. They notice a difficulty that someone is experiencing and instead of pointing out the inappropriate behavior, they simply express curiosity to collect more information. For example, “Ashley, I’ve noticed you’re having difficulty working with Tom during science labs. Help me understand what’s happening.” Ashley may have thrown the lab report dramatically on the floor and yelled, “You’re useless!” at Tom. However, recounting her behavioral choice is not where we start. (That would elicit a defensive response.) We start instead, with trying to identify what led to the behavior.

The request for more information (“What’s happening?) is followed by listening for and acknowledging the person’s feelings and then trying to connect those feelings to needs that are not being met well. For example, “It sounds like what matters most to you is having Tom complete his part of the work. Do I have that right?” This simple, empathic approach encourages people to tell us more about what triggered their behavior or what they need help with. Then, the listener can express their own concerns about the behavior chosen, and invite Ashely (who now does not feel attacked) to collaborate with them to find a solution that will work for everyone involved. That includes agreeing on a plan to make reparations for harm done to others. This conversation happens in private, between the adult who observed the challenging behavior and the child – not the assistant principal. The student senses the concern and support of the adult and has not been humiliated. A trusting, dependable relationship forms.

The alternative approach of sending students out of class or imposing consequences before understanding the situation, severs relationships between school adults and students and often leads to more isolation, frustration, anger and defiance. When staff learn to notice needs, they can find ways to allow a child to stay in their room or in school, while providing the time or alternate safe place to calm emotions before discussing the event.

When examining our discipline procedures, we can look through a different lens to notice when we are using control-oriented, punitive approaches that are uninformed and usually escalate a conflict. Replacing them with collaborative practices does not condone inappropriate behavior. Instead, it helps us to notice patterns of behavior and explore with the student what skill they might need help with in order to make a different, more beneficial choice. Safe schools recognize that most students who choose challenging behaviors do so because they have lagging skills that they need our help to strengthen. Excluding them at a time of need often makes matters worse. (See Collaborative and Proactive Solutions and Restorative Practices resources).

Which key element do you think ensures the success of the other two?

Let’s consider the three initiatives suggested and decide which one of them might serve best as the foundation for successfully accomplishing the other two.

- Model, teach and practice social and emotional skills with all

- Help adults to develop intentionally positive communication

- Replace control-oriented, punitive and exclusionary discipline practices with collaborative, humane

Which one of these initiatives ensures the success of the other two? If we don’t consider this question, we might find ourselves spending a great deal of time focusing on one of these important goals, struggling with the skills, overloading or alienating staff, and simply not realizing the intended benefits. So, which goal do you think provides a logical foundation for the other two?

Most teachers will initially choose “modeling, teaching and practicing SEL skills with all students” as their foundation. Their rationale is that it would be helpful for all students to learn these skills. While this is a really great goal, it often falls short of its intended benefits. The reason is that if we don’t help all of our school adults to model these skills in their interactions with all adults and students, we are sending a confusing, double standard message to our students. Even a primary age student can tell if their teacher is not managing their emotions well or reacting by blaming, judging or humiliating a child. If we teach students these skills, they need to be surrounded by examples of adults modeling these skills. This includes all adults in the building. That creates the safest, most consistent environment you can provide and ensures that your SEL lessons will realize their intended goal.

Some enthusiastic school leaders try to begin with instituting new collaborative and proactive discipline practices. The problem with this is that it's a totally uphill battle with staff members who feel most comfortable maintaining strict expectations and assigning consistent consequences. They don’t yet have the skills needed to engage students in non-judgmental conversations, collect information to discover what caused the behavior and then explore solutions. They often allow themselves to be triggered by inappropriate behavior and react emotionally. They too are acting without thinking. When we ask them to stop using what was working for them before they feel competent using new strategies, they likely will object to and argue against the initiative. Here again, the staff does not yet have the skills they need to let go of the punitive consequences they rely on to control the behavior of others. They need time to experience success with these new “doing with” approaches first.

Making adult communication skills the foundation of your school climate plan

When staff members are involved in learning about, discussing and even experimenting with the goals behind these three initiatives, they likely will come to an agreement that developing their own communication skills would serve as the best foundation to accomplish all three goals. We are all stressed and triggered by the pressures and frustrations in our lives. Having a few simple techniques to notice when we have been emotionally triggered, taking a moment to calm ourselves, and replacing a reaction with a thoughtful and curious response helps us to identify our own needs, as well as collect enough information to identify the needs of others. Without the opportunity to understand and practice these communication skills, the other two school improvement initiatives will quickly run into road blocks, resistance or regretfully get “shelved”. Positive communication skills help school adults to model SEL skills and let go of punitive approaches to changing student behavior. And, as an added bonus, relationships with colleagues, parents and our own family members improve as well.

There are many simple ways to explore positive communication skills. Suggested resources include learning about Invitational Theory and Practice, Mindful or Non-Violent Communication skills and Empathic Communication. Many of these strategies are also incorporated in formal evidence-based programs of SEL lessons, Ross Greene’s Collaborative and Proactive Solutions, and Restorative Practices. These three formal programs are wonderful, but they depend on positive adult communication skills being the norm.

After 17 years of exploring what transforms school climate, I’ve come to the realization that less is more. I recommend that schools not start by trying to implement a full-scale rollout of any of these comprehensive, formal programs. They are certainly a priority and worthwhile doing, but that can follow just a little later. Instead, set the stage for success by learning about and encouraging intentionally positive communication strategies with staff. Invite them to put the usual consequences aside and experiment with a collaborative approach to meet their needs, as well as discover their students’ needs. Offer to partner with them and assist with a difficult conversation or situation. Read, practice and learn together. Share success stories with others. You’ll discover that these simple changes in how we choose to communicate will help us all to become more perceptive, as we start by being curious. Then,

- listen for and acknowledge the feelings and needs of others,

- share our own feelings without blame or judgment, and

- invite collaboration to discover beneficial solutions

Developing dependable relationships and respectful schools is that simple.

Casel’s Five SEL Competencies

Self-Awareness

Self-Awareness

- Identifying emotions

- Accurate self-perception

- Recognizing strengths

- Sense of self-confidence

- Self-efficacy

Self-Management

- Impulse control

- Stress management

- Self-discipline

- Self-motivation

- Goal setting

- Organizational skills

Social Awareness

- Perspective-taking

- Empathy

- Appreciating diversity

- Respect for others

Relationship Skills

- Communication

- Social engagement

- Building relationships

- Working cooperatively

- Resolving conflicts

- Helping/Seeking help

Responsible Decision Making

- Problem identification

- Situation analysis

- Problem-solving

- Evaluation

- Reflection

- Ethical responsibility

2013 Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning