Adaptive Teaching: Finessing Great Teaching Practices

In every lesson, skills and environmental factors dictate that students will learn and achieve at different rates. Traditionally, teachers modify their instruction for students, and groups of students, to ensure that every student is engaged in learning at the appropriate level. Differentiated instruction became a key area of teacher accountability. Over time, the dutiful rituals of differentiated instruction developed lives of their own, and they were seen as external accountability measures imposed on teachers that were checked by school administrators. PISA/OECD is proposing a different way to finesse, and re-invigorate differentiation.

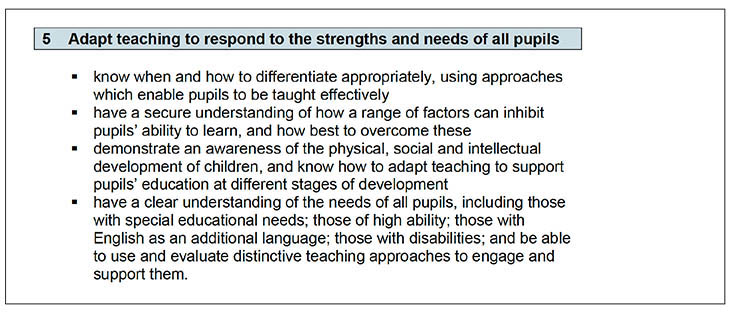

Subsequently, the United Kingdom Department for Education (2021, p. 11-12) has included a section on adaptive teaching in its Teachers’ Standards that opens with the imperative instruction - The teacher must -

Differentiated Instruction and Adaptive Teaching

Differentiated instruction has been in classrooms since the modern models of teaching emerged in the post-Industrial Age, particularly where one-teacher schools catered for students of all ages. Carol Ann Tomlinson (1999), an acknowledged guru of differentiated instruction, made the point of teachers addressing individual students’ needs: “In differentiated classrooms, teachers provide specific ways for each individual to learn as deeply as possible and as quickly as possible, without assuming one student’s road map for learning is identical to anyone else’s (p. 2).” In terms of logistics, this emphasis on individualisation of instruction places a heavy instructional burden on classroom teachers.

At the present time, in Australia, there is an expectation that instruction will be differentiated. Individual Education Programs (IEPs) are seen as the major tool for formal differentiation, however, herein lies the problem. This static, pre-planned, term-based exercise of writing IEPs is not situationally responsive to students’ day-to-day educational needs, and does not respond in a contextual sense to issues that arise spontaneously. Prospero (2022) noted:

'Adaptive teaching involves teaching the same lesson objectives to all students whilst providing scaffolds to support all students in making progress. Adaptive teachers will have a deep understanding of the needs of their students. They will have a range of strategies at their disposal that can be used in a range of ways throughout a single lesson, including:

- Questioning, purposeful interventions, fostering quality discussions.

- Planned learning activities that are appropriate for the whole class.

- The ability to learn from and collaborate with other educators' (Prospero, 2022).

The current push to adaptive teaching has come from PISA (2019), which responded to data generated by the analyses of the 2018 PISA results. The PISA (2019) analysis found that students described some of the characteristics of adaptive teaching as:

“The teacher adapts the lesson to [my] class’s needs and knowledge”; “The teacher provides individual help when a student has difficulties understanding a topic or task”; and “The teacher changes the structure of the lesson on a topic that most students find difficult to understand”.

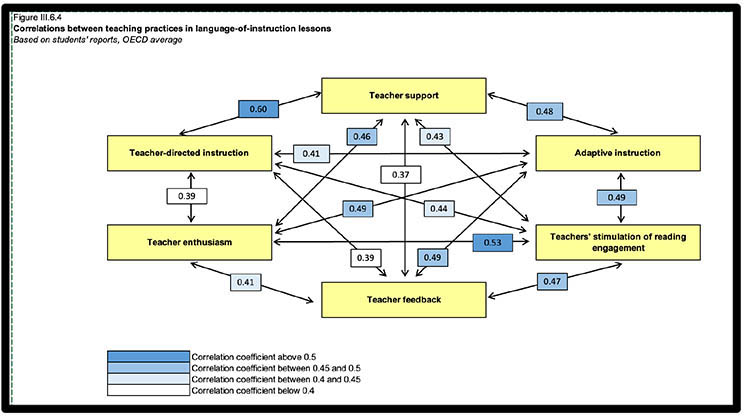

In Figure 1 (below) adaptive instruction sits within the instructional constellation of teaching practices in the PISA 2018 analysis.

Figure 1 Correlations Between teaching Practices PISA 2018 Analysis.

[From PISA (2019). PISA 2018 results, p. 104]

[From PISA (2019). PISA 2018 results, p. 104]

We acknowledge that there are some formal requirements to use IEPs in reporting students’ progress to external agencies. However, we think that IEPs and Adaptive Learning complement each other. Smart and measurable IEP goals should result in a conscious daily, informal, reflective process, (“What do I need to do to help this student achieve this particular goal?”) and they should guide a teacher’s strategic understandings, and not facilitate separatist group work with an education assistant. With Adaptive Learning, teachers use their current knowledge and skill of students to determine the ‘on the spot’ teaching that moves the student closer to the broader, reportable IEP goal.

Adaptive Teaching: Knowing What to Look For

In every activity there are levels of knowing. For example, families watching the Olympic diving competition all have opinions on what looks like a gold medal dive, and often something like the amount of splash becomes the main criterion of excellence. Likewise, the stay-at-home family that goes to a fancy restaurant for a special occasion thinks that the best wine on the wine list is the most expensive! Judging expertise comes with knowledgeable practice and expert feedback. We argue that a group of teachers watching a video of a teacher teaching will all see different things, and it often takes expert practitioners (educational cognoscenti) to pick the unobtrusive actions that constitute adaptive teaching practices. This, to a degree, links to the arguments that Boyd, Harris and MacNeill (2022) explored in the “Curse of Knowledge: Do you know what I know?”

Firstly, adaptive teaching does not reside as the sole domain of the classroom teacher. Every adult in the class has an adaptive teaching role, which is what we often see in the Early Childhood Education classes, and, it is the quality of the education assistants’ pedagogic interactions that help define adaptive teaching and learning in classrooms.

Secondly, as the Department for Education UK (2021) Teaching Standard 5 indicates the quality of adaptive teaching and learning starts with the teacher-student relationships, and knowledge. The standard has an imperative quality: The teacher must - …. Therefore, adaptive teaching is not something that teachers can ignore.

Thirdly, Julie Wharton (2023), writing in the Times Educational Supplement, noted: “Some may argue that adaptive teaching is the same as differentiation, but there is a crucial difference: adaptive teaching starts with the whole class, whereas differentiation focuses on individuals.” But, the essence of adaptive teaching, according to Wharton, lies with the micro-adjustment that great teachers can make on the run:

'Once the lesson is underway, adaptation in the moment is key to maximising learning. Teachers who know their class well will quickly pick up on dips in concentration or notice when pupils seem unsure. Quick, ongoing formative assessment and good communication with the additional adults in the room allow for small adjustments to be made to the task, enabling a pupil to achieve success. For example, a teacher might use questioning to activate prior knowledge, or allow children time to talk and problem-solve. They may decide to elicit a pupil’s response in a different way, if they can see that a pupil is struggling to communicate their ideas.'

The depth of these micro-adjustments to lessons and interactions may not be recognised by many external observers who are unaware of the history, or context, of each relationship.

In summary, the differences between differentiation and adaptive teaching are clear (see Table 1, below), but they are often not easy to discern for external observers. For example, the teacher in an adaptive teaching lesson may walk past a student and give his work a cursory glance. To the casual observer this is taken at face value for the struggling student however, the body language and slight nod of the head is recognised by the student as an acknowledgement of success with the concept.

One important point to note on the influence of E.D. Hirsch, and focussing on the whole class. Is that differentiated instruction in primary schools saw students with the most needs often being assigned to work with education assistants, separated from the main class. This was problematic on two counts. First, the physical isolation from the class, and second; the failure to mix with more successful students.

It is important to note that the British model of adaptive teaching has specific requirements, and should not be confused with some minor attempts at changing teachers’ pedagogy that do not meet the eight characteristics listed in Table 1. A teacher may claim that changing the desk alignment in a class is an example of adaptive teaching, but that does not fit this adaptive teaching lens, which is tightly focussed on the teaching act.

Table 1 An Analysis of the Difference Between Differentiation and Adaptive Teaching (Huntington Research School, 2023).

| Differentiation | Adaptive teaching |

| Must, should could learning objectives | Focussed support for young people |

| Capped expectations for those who need the most support | Tweaks to lessons |

| Individualised learning plans | Targeted catch up |

| An array of pre-planned resources | One lesson for all students |

| Mini lessons for different groups of learners | Judging in the moment whether students are coping |

| There is a ceiling to progress and learning | Emergent needs are catered for by tweaking the lessons |

| Identifying students in the moment who may need more scaffolding | |

| Starting points planned so all can be successful |

Case Study

The following observation of an Early Childhood Teacher teaching Foundation students to read and spell words illustrates the importance of Adaptive Teaching when catering for a range of student abilities. The teacher began by task analysis, that is reviewing the precursor skills required to read and spell bank, left, sand, lamp, bump, vest, soft, belt, lend, milk and spit. Beginning with a slide featuring single letter-sounds that all students recited with the teacher at pace, she then called on individual children to identify sounds, starting by asking more able individual students to say the sound of each letter as she touched it before asking some less able individual students who benefited from hearing the answer from their more able peers. Phoneme segmentation, or breaking words into sounds is an essential precursor for decoding (reading) and encoding (spelling words) so students were partnered and stood up to ‘clap out’ the letter-sounds one phoneme at a time. For the word bank, students clapped out b-a-n-k and other words as the teacher joined in with a student demonstrate what was required. Once the students sat back down three pairs stood up and demonstrated they could clap out a different word. In this instance, after three words already practised by the students were demonstrated, the teacher chose an able pair and asked them to clap out g-r-ou-n-d, a longer word. This movement activity served to maintain the attention of the students who enjoyed working with a partner as well as challenging the more able students. Bringing together the first two tasks, the teacher then modelled how to decode bank, left, sand, lamp, bump, vest, soft, belt, lend, milk, spit and the students repeated after her. Handing out whiteboards the teacher demonstrated how to spell bank, left, sand, lamp into sounds and students wrote these on their boards. In the top right-hand corner of the whiteboard the teacher had a ‘genius’ box with the required letters that the teacher referred to for weaker students pointing to each letter as she demonstrated how to spell a word. The more able students did not require any prompting. Finally, after checking the students could spell the words the teacher had a final screen split into three sections. The teacher then asked the more able students to use two of the following pictures (milk, soft, lend, list) in a ‘Who, what it did’ sentence structure. The middle ability group were asked to write bank, left, milk on their white boards using pictures on the screen as a prompt. Finally, the least able students saw pictures of bank and vest with a partially spelt word (b_n_) and vest (_e_t) and in the same amount of time allocated to their peers were required to spell these words on their whiteboards.

The instructional sequence took 10 minutes to deliver, and students responded over 45 times either saying, sounds, reading words or spelling words. Mostly, students responded all together with specific opportunities to show the teacher what they had learned at the end of the lesson.

Discussion

All school leaders know great teaching when they see it. It represents the combination of a complex algorithm that integrates many active variables. That “WOW” moment of recognition is something that we treasure, and when we see this occurring, we ask ourselves, ‘how are these variables being manipulated and utilised to create these wow moments?”.

What draws us to Adaptive Teaching is that it is based on an expert understanding of each student’s levels of learning, a sensitive understanding of students’ body language, and reactions. Teachers working in the adaptive paradigm know their audiences, they are perceptive enough to engage the students’ zones of proximal development in scaffolding lesson developments as they move through the learning sequence. For us, by matching our pedagogic practices against the key expectations of adaptive teaching, assures us that our teachers were developing the finessing skills that accompany expert teaching.

It is important to recognise that Daniel Muijs (2023) has sounded a timely warning about the implementation of adaptive teaching in schools:

'So, whenever we decide to introduce adaptive teaching, it is worth ensuring that we don’t just impose it without the support and development needed. It’s also important that we don’t assume that adaptive teaching is something we need to emphasise for novice teachers. For them, the classroom is a complex enough place without the additional demands of adaptive approaches. In summary: adaptive teaching can work, but we have got to make sure it’s not introduced unthinkingly or without the necessary support.'

We believe that this Adaptive Teaching will make a real difference to students’ learning, and alleviate the labelling problems associated with some applications of differentiated instruction.

References

Boyd, R., Harris, M., & MacNeill, N. (2022). The curse of knowledge: Do you know what I know? Education Today. https://www.educationtoday.com.au/news-detail/The-Curse-of-Knowledge-5523

Huntington Research School (2023, January 24). Adaptive teaching: What the Core Content Framework for ITTs can help us understand about the shift from differentiation to adaptive teaching. https://researchschool.org.uk/huntington/news/adaptive-teaching

Muijs, D. (2023, May 4). Is it time to ditch differentiation? The Times Educational Supplement. https://www.tes.com/magazine/teaching-learning/general/adaptive-teaching-ditch-differentiation-teachers

PISA (2019). PISA 2018 results: What school life means for students’ lives. Paris: PISA. https://www.oecd.org/publications/pisa-2018-results-volume-iii-acd78851-en.htm

Prospero (2022, November 9). Differentiation v. adaptive teaching. https://www.prosperoteaching.com/blog/2022/11/differentiation-vs-adaptive-teaching

Tomlinson, C.A. (1999). The differentiated classroom: Responding to the needs of all learners. ASCD.

United Kingdom Department for Education (2021). Teachers’ Standards. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1040274/Teachers__Standards_Dec_2021.pdf

Wharton, J. (2023, March 3). How to get adaptive teaching right. Times Education Supplement.