Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) and Trauma Informed Schools

The true scale of the impact of trauma on the students in our schools is sadly under-estimated, and, in reality, the school staff members often only ever see the tip of the iceberg because many traumatised students have often been taught never to reveal what happens in homes and family situations. In the United States and Britain a new wave of awareness of childhood trauma is sweeping through schools in the shape of the Trauma Informed Schools movement, and we can expect that Australia will follow this trend.

Awareness of childhood trauma is often discussed by school staff who are concerned about the impact on their students. In 1998, Felitti, et al. had coined the term Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) to describe these traumatic experiences traumatised children had faced. Furthermore, these authors found that

‘(b)ecause adverse childhood experiences are common and they have strong long-term associations with adult health risk behaviors, health status, and diseases, increased attention to primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention strategies is needed’ (p. 254). To help quantify the ACE data Felitti, et al. (1998) developed the ACE survey and the data for Adverse Childhood Experiences survey revealed the dimensions of this issue, with the American data (Sacks, Murphey & Moore, 2014, p. 1) claiming that 46% of American children have experienced an ACE.

The eight ACEs that were measured in Felitti’s original research included:

1 Lived with a parent or guardian who got divorced or separated

2 Lived with a parent or guardian who died

3 Lived with a parent or guardian who served time in jail or prison

4 Lived with anyone who was mentally ill or suicidal, or severely depressed for more than a couple of weeks

5 Lived with anyone who had a problem with alcohol or drugs

6 Witnessed a parent, guardian, or other adult in the household behaving violently toward another (e.g., slapping, hitting, kicking, punching, or beating each other up)

7 Was ever the victim of violence or witnessed any violence in his or her neighborhood

8 Experienced economic hardship ‘somewhat often’ or ‘very often’ (i.e., the family found it hard to cover costs of food and housing). (Sacks, Murphey & Moore, 2014, p. 2).

Romero, Robertson and Warner (2018, p. 3) viewed ACE as an equal opportunity occurrence with some 60% of one research sample indicating that they had directly or indirectly been exposed to ACE. However, the interface between ACE and trauma is pertinent in the school environment because of its impact on students’ learning.

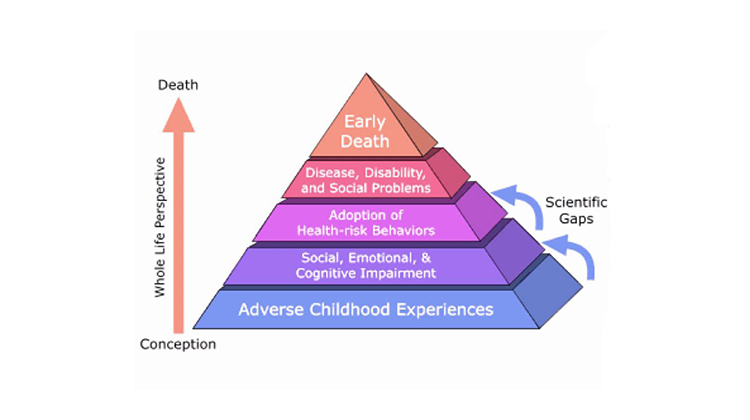

It is important to acknowledge that the ACE instrument was developed by medical doctors examining aspects of preventative medicine. The prestigious CDC Centres (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States) developed the ACE Pyramid from this research (Figure 1), which is designed to show the linkage between ACE and the quality of life and death (2014). Teachers too often hypothesise about the impact of ACE on students’ education and their future lives.

Figure 1. The ACE Pyramid. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014)

In education, there is now a growing body of research in relation to the effect of trauma on students’ learning. The ACE construct will help schools to better understand their students, and then shape Individual Education Programs (IEPs) and Trauma Informed School cultures to support their students’ learning.

ACE survey

The Kaiser ACE survey has 10 items that fall within the three categories of abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction (Table 1).

| Abuse | Neglect | Household Dysfunction |

| 1 (physical) | 4 (physical) | 6 ( Divorce) |

| 2 (emotional) | 5 (physical/emotional) | 7 (Mum treated violently) |

| 3 (sexual) | 8 (substance abuse) | |

| 9 (Mental illness) | ||

| 10 (incarcerated relative) |

Table 1. Summary of Kaiser ACE Survey

|

Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) Survey (Philadelphia revision) |

|

1 Emotional Abuse |

|

2 Physical Abuse |

|

3 Sexual Abuse |

|

4 Emotional Neglect |

|

5 Physical Neglect |

|

6 Domestic Violence |

|

7 Household Substance Abuse |

|

8 Parental Separation Not asked in this revision. |

|

9 Incarcerated Household Member |

|

Expanded ACE |

| 10 Witness violence How often, if ever, did you see or hear someone being beaten up, stabbed, or shot in real life? Many times, a few times, once, never Not asked Felt Discrimination |

|

11 Felt Discrimination |

| 12 Adverse Neighborhood experience Did you feel safe in your neighborhood? All of the time, most of the time, some of the time, none of the time Did you feel people in your neighborhood looked out for each other, stood up for each other, and could be trusted? All of the time, most, some, none of the time |

|

13 Bullied |

|

14 Lived in foster care |

Table 2. Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) Survey (Philadelphia revision, Cronholm et al. 2015)

However, more recent development of ACE that was trialled in Pennsylvania by Cronholm, et al. (2015) further developed the original ACE scale to measure a wider socio-demographic sample. The authors claimed the extended instrument picked up an extra 13.9% of the sample who would not have been identified in the earlier Kaiser ACE survey.

ACE Awareness and Trauma

Informed Schools

The original research that developed the concept of Abusive Childhood Experiences is now over two decades old. But what we can now see is that schools and school systems are becoming more aware of the ACE research and survey as they address student trauma. ACE Response (2019) stated that:

‘Teachers, school administrators, parents, and others within and beyond the education sector are teaming up to create healthy and supportive school environments that promote the academic success of all students. Schools like Cherokee Point Elementary School in San Diego, California and Lincoln High School in Walla Walla, Washington are applying trauma-informed methods to help make their kids feel safe, connected, and ready to learn.’

Tamara Fyke (2018) confirmed that the new interest in ACE is a result of mental health and resilience development in schools, and the growth of the trauma informed school movement in the United States.

Schools in Britain are now increasingly using the ACE survey and Lauren Smith (2018) reported that ‘… references to adverse childhood experiences have increased tenfold at a steady pace, suggesting a significant growth in discourse around the concept.’

Transmitted trauma and ACE

While the American ACE research mainly concentrates on direct, violent acts, in contrast, transmitted trauma is often overlooked in busy schools because its causes are often historic, and it is deeply embedded in family narratives. In Australian schools the transmission of trauma on Jewish families that survived the Holocaust is well acknowledged, but it often falls outside the domain of responsibility for school psychologists in public schools. Less understood is the raw transmission of Indigenous trauma. The Stolen Generation is reasonably well documented, but the embedded trauma for children in some communities is overwhelmingly traumatic and it requires multi-agency action. Atkinson’s (2008) research of Aboriginal families showed:

‘… that the normalisation of family violence and the high prevalence of grief, loss and substance misuse were as much symptoms as causes of traumatic stress. One of the most alarming aspects of Atkinson’s study was the consistency of identifying as being victims of particularly severe child sexual abuse from early ages. This abuse, which often began in early childhood (victim) and continued until maturity, triggered the later acting out (perpetrator) on members of extended family and others. Atkinson’s research also identified a substantial lack of services that effectively supported victims of abuse and interrupted its intergenerational progression. Atkinson concluded that the link between childhood trauma and adult offending was mediated by the presence of unresolved trauma and undiagnosed PTSD’ (Atkinson, Nelson & Atkinson, 2010, p. 137).

The influx of refugees into Australia from areas of conflict has also given another dimension to the trauma issues in our schools.

Conclusion

Schools are expected to be safe places for students, and we transmit that value daily by dealing fairly with students and addressing issues such as bullying in a timely manner. Trauma continues to be the elephant in the room for school staff, and the ramifications of this issue are so complex that school staff often act as first responders, and then coordinate their school’s responses to other lead agencies.

The ACE research is vital because it links schooling, students’ health, and their adult health and quality of life prospects. For Australian schools this is really important, and we can view the brilliant TED Talks that support our awareness building:

https://www.ted.com/talks/nadine_burke_harris_how_childhood_trauma_affects_health_across_a_lifetime

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ccKFkcfXx-c

It is timely to remember that in schools we receive information about students, but don’t actively investigate this area because other agencies have jurisdiction. Our guide for action in this domain is always: listen and then ask for help from authorised agencies.

The Adverse Childhood Experiences survey is not a clinical or precise instrument because it is a summary, or an overview that is designed to quantify the range of adverse childhood experiences. When the ACE data is made available to schools its use can be a key part of amelioration actions as schools develop plans to build Trauma Informed Schools, which is the way of the future.

References

ACE Response (2019). ACEs in Education. Retrieved from http://www.aceresponse.org/give_your_support/ACEs-in-Education_25_68_sb.htm

Atkinson, J., Nelson, J., & Atkinson, C. (2010). Trauma, transgenerational transfer and effects on community wellbeing. In N. Purdie, P. Dudgeon, & R. Walker (Eds), Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Canberra, ACT, pp. 135-144. Retrieved from https://www.aipro.info/wp/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Trauma_transgenerational_transfer.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2014). The ACE pyramid. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy/pyramid.html

Felitti, V. (Producer) (2010). The Relationship of adverse childhood experiences to adult health status. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Me07G3Erbw8.

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 14(4), 245–258.

Fyke, T. (2018, January 25). Addressing adverse childhood experiences in school. ASCD Express, 13(10). Retrieved from http://www.ascd.org/ascd-express/vol13/1310-fyke.aspx

Romero, V.E., Robertson, R., & Warner, A. (2018). Building resilience in students impacted by Adverse Childhood Experiences: A whole staff approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Sacks, V., Murphey, D., & Moore, K. (2014, July). Adverse childhood

experiences: National and state-level prevalence (Research

Brief), Child Trends. Bethesda, MD: Childtrends.org. Retrieved from https:// childtrends-ciw49tixgw5lbab.stackpathdns.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Brief-adverse-childhood-experiences_FINAL.pdf