Aporophobia: Poverty is Not a Learning Disability (for discussion)

Children living in poverty have always been a part of the schooling context, and the pernicious effects of poverty cannot be ignored. Acknowledging this situation, it is useful for teachers to reaffirm that poverty is not a learning disability despite students below the poverty line often filling seats within remediation classes. The issue of poverty is a societal issue that schools’ staff can successfully resolve, but its recognition can provide a good starting platform from which to begin informed discussions.

Seldom does educational literature mention, for example, that student achievement outcomes are more honestly a reflection of the economic advantages and disadvantages seen in a wider social context, and that there exists a high correlation between student achievement and the child’s socio-economic background. Important characteristics such as the parents’ occupation or level of education, the family’s income bracket or the location of the students’ post code are often much better predictors of academic success. Experienced educators know that student literacy and numeracy levels are often directly related and influenced by a child’s economic background, and hence the obvious link with aporophobia.

“Aporophobia: Why we reject the poor instead of helping them”

The term aporophobia was coined by the Spanish professor, Adela Cortina, in her analyses of people’s attitude toward the poor, which she saw as a systemic rejection towards poverty and people without resources. Cortina (2022, p. 6) further explained:

'It is the poor person, the aporos, who is an irritation, even to his own family. The poor relative is considered a source of shame it is best not to bring to light, while it is a pleasure to boast of a triumphant relation well situated in the academy, politics, art, or business. It is a phobia towards the poor that leads us to reject individuals, races, or ethnic groups that in general lack resources and therefore cannot - or appear unable to - offer anything.'

Poverty can mean different things to different people, however, Cortina (2022) examined poverty as a consequential lack of freedom. In her modelling for addressing the poverty issue she put forward two steps:

- The first step in eliminating poverty is addressing these needs and freeing oneself from them (p. 108); and

- In broader terms she says “… we must consider those who lack freedom, who lack the capacity to bring into their chosen life plans or control of their lives in any substantive way (p. 108).

These steps are predicated on poverty being eradicable.

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority Reifying the Poverty: Intelligence Equation

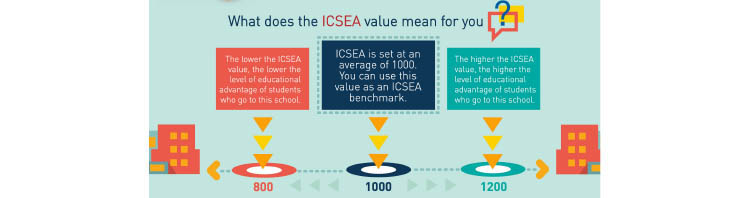

Poverty has a major impact on individuals’ lives, and as teachers we know that it influences students’ academic trajectories and opportunities. ACARA, and others, appear to formally condition the population to equate poverty with lack of educational capacity within their ICSEA-type algorithm. Those teachers with backgrounds in scientific methodology know that correlation does not mean causation, but for the majority of readers of the NAPLAN data, what these data clearly show is that the schools from the high SEI/ICSEA (Index of Community Socio-educational Advantage) areas generally outscore the results for schools in the low SEI/ICSEA areas. Therefore, a judgmental interpretation will be - the rich always do better at schooling than the poor.

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) employs the ICSEA algorithm to determine like-schools comparisons. ACARA (2014) claimed:

'ICSEA was developed to enable comparisons of NAPLAN results between schools on the My School website. By comparing performance in schools working with students with similar socio-educational advantage, it is claimed to be able to identify the difference similarly ranked schools are making to the students attending a particular school. The index also enables schools seeking to improve their students’ performance to learn from other schools with similar students.'

The input factors in the ICSEA algorithm include parents’ education, parents’ occupation, Indigeneity, and geographic location. The specific weightings of these factors are not made available.

Figure 1 ACARA’s Visual Explanation of ICSEA as a Factor of “Educational Advantage”

Based on the four input factors of parents’ education, parents’ occupation, Indigeneity, and geographic location, Figure 1 shows the linkage between parent’s educational achievements and occupations as a part of the four factors that generate lower levels of educational “advantage”, whatever that may be. The advantage concept is deliberately obscurantist, and this can result in a classic example of blaming the victims. At the present time, while the school median scores used for comparisons in NAPLAN testing have been removed, the ICSEA rankings clearly set out comparative socio-economic rankings for parents, and real estate agents who sell houses around the high achieving schools.

Poverty Affecting School-Based Learning

The promise of educational success is predicated on a student’s ability to delay long-term gratification. This is problematic for poverty affected students and as Horacio Sanchez (2021) noted: “The higher your stress or emotional instability, the lower the ability to delay gratification. Cognitive load reduces the ability to devise and maintain long range plans” (p. 69). Further complicating the educational success algorithm is the mass of personal-familial issues that affect a poverty strickened student’s academic performance: resources (book, pens); middle-class language proficiency; school uniforms (clothes, shoes); homework support (lighting, computer, desk, chair, and quietness); money for incursions and excursions; and a stable home background (food, sleep, own clothes, own bed); familial support for education (value education, trust of the school, and school attendance encouragement).

Education is broader than what happens in classrooms, and as Joe Bageant (2010) recounted that as a dirt-poor, displaced farmer’s child he had to attend middle school in a larger town, where, because of his appearance:

‘… many of us were put in what was openly called ‘the dumbbell room,’ a special classroom for the sub-intelligent and back-country kids…. Here I was in the dumbbell room with the so-called retards, fist fighters, and drooling crayon eaters. The usual stated reason was ‘behavioral problems’’ (p. 160).

While Bageant’s experience was extreme, the physical appearance of poverty still influences interactions in schools, as could be seen in highly effective the Smith Family’s charitable appeals to help children living in poverty.

Poverty Linked Behaviour in Schools

Students from poverty-stricken environments often appear different to many of their fellow students, and they often lack the equipment and resources needed for the schools’ learning programs. Research has shown that being perceptibly different can be problematic in some environments, and as Attree, (2006, p. 59) noted:

'An important theme of the review is the social costs of poverty for children, in particular its effect on friendships and social inclusion. Middleton and others (1994) argue that the constraints on social participation associated with poverty mean that children begin to understand the reality of being ‘different’ at an early age. However, children described the impact of poverty on their lives in different ways.'

The extensive work on poverty by Ruby Payne (1995) has identified behaviours related to poverty. The list of behaviours included: Laughs when disciplined; Argues loudly with the teacher; Angry response; Inappropriate of vulgar comments; Physically fights; Hands always on to someone else; Cannot follow directions; Extremely disorganised; Only completed part of a task; Disrespectful to teacher; Harms other students, verbally or physically; Cheats or steals; and Constantly talks (p. 48). It is interesting to see these behaviours listed, and challenging to see how the behaviours can be changed at the school-level.

There are many causative factors in the aberrant behaviours of students experiencing poverty, and much of the research discusses of post-traumatic stress disorder. However, Kevin Johnston (2019) made a strong point about the difference between PTSD and CPTSD (Complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder), where bullying can be ongoing for children living in poverty:

‘Children living in poverty can stand out from the crowd because of dirty clothes, holes in shoes, unkempt hair, and poor personal hygiene. Bilic (2015) reported that almost all socioeconomic variables that suggest that a family is poor correlate significantly with victimization, and the results from the same study denoted that 34.8% of those living in poverty responded violently toward peers because of their more inferior financial status, and 45.7% were bullied and victimized for being poor’ (p. 85).

As a result of the covert and overt bullying that accompanies being different in schools the children living in poverty often coalesce into protective gangs.

Summer Learning

For many students from what could be described as poverty stricken circumstances, schools provide a safe, stable environment that often provides food and clothing. While most students rejoice at the end of the school year there is a small proportion of students who know that school vacations will be a time of stress.

In the educational sense, an opt-in summer learning program makes good sense, particularly as this would attract a different mix of students, be fully supported, and pick up aspect of learning they may have missed- such as swimming lessons, sport and aspects of the cognitive learning program to allow relearning.

The Oxford Learning (2019) article on summer learning loss provides useful reasons for schools to consider summer learning.

This article sets out important information about summer learning loss, and the need to address that at the start of every school year.

This article sets out important information about summer learning loss, and the need to address that at the start of every school year.

Discussion

For most children living within the poverty cycle, school is not a pleasant place. Rather it is a place where their knowledge, dress, and appearance allow odious, often unstated, comparisons to be made. There are, however, aspects of poverty that can be addressed in children’s education:

- Addressing the food and resourcing issues for all children living in poverty;

- Addressing the safety, cleanliness and dress issues;

- Addressing an attainable future for every student; and

- Growing self-esteem, and achievement in students experiencing poverty.

While the late Bob Hawke had a dream about supporting children living in poverty, support and strategies need to be more focussed to ensure that students get an education that will allow them to participate fully in Australian society, rather than be condemned to living on the fringes from the time they were born.

In schools, we need a concerted Australian effort to banish aporophobia, to break the poverty cycle, and to give every child a fair go. This change is bigger than a school-based collection of strategies, and it requires a commitment to a cultural valuing, such as Ubuntu (MacNeill & Boyd, 2023) in which an individual’s humanity is fostered in a network of relationships - I am because you are; we are because you are; which then can drive the more communal sense of reciprocal care.

References

ACARA (n.d.). What does the ICSEA value mean? Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. https://docs.acara.edu.au/resources/20160418_ACARA_ICSEA.pdf

Attree, P. (2006). The social cost of child poverty: A systematic review of the qualitative evidence. Children and Society, 20, 54-66.

Bageant, J. (2010). Rainbow pie: A redneck memoir. Melbourne: Scribe.

Cortina, A. (2022). Aporophobia: Why we reject the poor instead of helping them. Princeton University Press.

Johnson, K. (2019, October). Chronic poverty: The implication of bullying, trauma and the education of poverty-stricken population. European Journal of Educational Sciences. http://ejes.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/6-oct-6.pdf

MacNeill, N., & Boyd, R. (2023). Ubuntu: Developing new pedagogic relationships in schools. Education Today. https://www.educationtoday.com.au/news-detail/Ubuntu-5866

My School (2016). Guide to understanding 2013 Index of Community Socio-educational Advantage (ICSEA) values. https://docs.acara.edu.au/resources/Guide_to_understanding_2013_ICSEA_values.pdf

Oxford Learning (2019). Summer learning loss Statistics (And Tips to Promote Learning a Summer Long). https://www.oxfordlearning.com/summer-learning-loss-and-how-to-prevent-it/

Payne, R.K. (1995). A framework for understanding poverty. Aha Process Inc.

Sanchez, H. (2021). The poverty problem: How education can promote resilience and counter poverty’s impact on brain development and functioning. Corwin.