Bored or Burned out? Re-imagining School Facilities to better Support Teachers and Students

Introduction

In the Amazon Jungle, the Sahara Desert, and the Himalayan foothills, the K-12 classrooms I have visited are all similar. In the United States and Europe, an identical model prevails. With little variation, a dynamic teaching wall, a passive inspirational wall, a window wall, a matrix of desks or tables, and a single teacher guiding the proceedings is a globally accepted norm. Schools are largely monocultures of these identical spaces.

Sure, there are exceptions. Gyms, libraries, cafeterias, science labs, art rooms, wood shops, metal shops, makerspaces, and other specialized venues devoted to skill building offer alternatives. However, in public school, across divergent cultures, students spend much of their time in a standard classroom. Teachers everywhere are expected to unilaterally bring those rooms and those students to life by force of their personality and some limited resources.

Nonetheless, high teacher attrition and low student engagement in the United States begs the question: what more can be done to improve public schools? Consider the following approach to the K-12 school that I believe will better serve teachers and students.

Foundation: Peak Experience

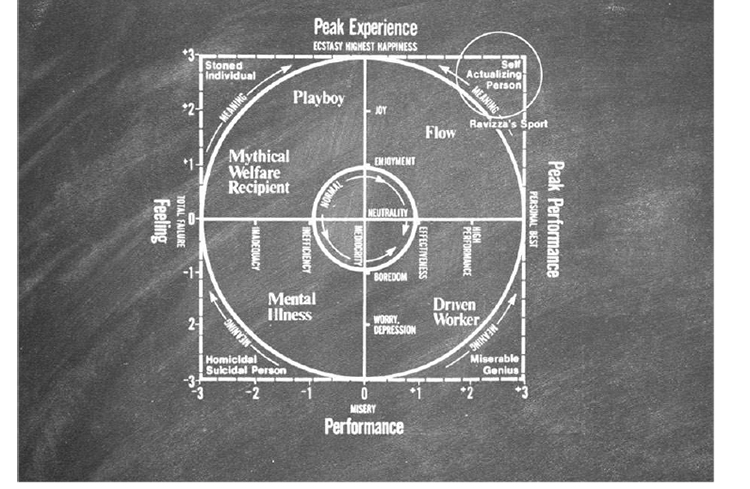

I found inspiration in the work of Dr. Gayle Privette (1985), who posited that only peak performance matched by peak experience could open the gates to flow and self-actualization.

The invitation to work hard will only resonate if students are rewarded with a sense of empowerment and joy. Performance without joy yields a miserable workforce. Joy without effort eliminates the satisfaction of accomplishment.

Figure 1: Plotting Feeling against Performance (Privette, 1985), highlight (top-right) by the author.

Schools certainly demand peak performance from their students. When, however, do they take consistent responsibility for the quality of their students’ emotional experience? Social Emotional Learning (SEL) (CASEL, 2020) seems more focused on socialization than self- actualization. Emotional and Cognitive Aspects of Learning (ECOLE) (Glaser-Zikuda et al., 2005) and Fear Envy Anger Sympathy Pleasure (FEASP) (Astleitner, 2000) do not emphasize accomplishment, joy, flow or self-actualization, and do not reference the Physical Learning Environment (PLE) as a variable, so entrenched is the idea of a classroom.

Meanwhile, teacher attrition in the United States at 8% per year and up to 20% per year in high-minority, high-poverty schools continues to erode instructional quality. Up to 50% of starting teachers leave the profession within 5 years of starting, leaving before their accrued experience truly makes an impact (Ingersoll et al., 2018). Furthermore, student engagement plummets to as low as 33% in high school (CalSCHLS, 2021; Gallup, 2016).

Catalyst: Communities of Practice

What drives teacher burn-out and attrition? Offering teachers their own classroom promises agency and autonomy; however, the resulting isolation proves counter-productive, especially for young teachers early in their career. “Egg-crate isolation” (Lortie, 1975) contributes to teacher attrition (Arnup & Bowles, 2016; Carlson & Thomas, 2006; Haynes et al., 2014; Ingersoll et al., 2018; Ostovar-Nameghi & Sheikhahmadi, 2016).

Brown and Settoducato (2019) quoted one teacher as follows:

'Teaching can be incredibly isolating... We write learning outcomes alone, design activities alone, and teach behind a closed door. We reflect, review assessments, and enter statistics alone. How can we build communities of practice when our work is often done in isolation?' (p. 10).

Additional factors include the lack of “school culture and collegial relationships, time for collaboration, and decision making input” (Sutcher et al., 2016, p. 52). One teacher’s blog (Kruse, n.d.) also implicates monotony, boredom, stasis, and confinement in teacher burn-out.

I propose to shift the creativity teachers bring to their own classrooms into a more communal realm by imagining schools that physically embody communities of practice (CoP). Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner (2015) defined CoP as 'groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly' (p. 2). Members of a CoP share a domain (some specific area of interest), they share a practice (activities directed towards specific goals), and they define themselves as a community (identification with the group).

Practically, this means moving teacher desks out of private classrooms and into communal workrooms (I call them hives) with like-minded peers. These hives offer teachers a semi-private professional workstation, collaboration tables, whiteboards, project rooms, and ample storage, with access to refreshments and the outdoors. Here, true mentorship between new and experienced teachers receives more than ad hoc support. Here, teaching materials are efficiently shared. Here, starting teachers receive the support, build the community, develop the expertise, and assume the identity of a professional, without which they leave the profession.

Grouping like-minded teachers may be useful but it is no panacea. Lortie (1975), in his expansive exploration of teacher sociology, notes:

'Unless beginning teachers undergo training experiences which offset their individualistic and traditional experiences, the occupation will be staffed by people who have little concern with building a shared technical culture.' (p. 67).

Indeed, convincing teachers that giving up private domains for shared accommodations is a net win may be challenging. Those hives better be good.

Belenardo (2001) specified six dimensions of a sense of community: “shared values, commitment, belonging, caring, interdependence, and regular contact” (p. 34). This resonates strongly with the Wenger-Traynors regarding CoP, emphasizing the psychosocial quality of the arrangement. It highlights the importance of grouping like-minded professionals.

Laurence et al. (2013) identified architectural privacy as a key bulwark against burnout: 'When people experience their work environment to be low on privacy, it enhances the pressure on them to divide their mental attention between pursuing work assignments and handling the distractions, interferences, and feelings of being monitored that are associated with low experience of privacy. This need to divide attention between work and non-work related issues is likely to tax people’s mental ability, resulting in increased emotional exhaustion over time.' (p. 145).

Laurence et al. note, however, that personalizing personal space mitigated the effect of privacy concerns. I know this to be the case from decades of collaboration in architectural studios: the opportunity for self-expression in a shared space energizes a shared mission with camaraderie.

A. S. Neill (1960), the founder with his wife, Frau Doktor L. A. Neustatter, of the iconic Summerhill, identified freedom as fundamental to communal well-being:

'In most schools where I have taught, the staff room was a little hell of intrigue, hate and jealousy. Our staff room is a happy place. The spites so often seen elsewhere are absent. Under freedom, adults acquire the same happiness and good will that the pupils acquire. Sometimes, a new member of our staff will react to freedom very much as children react: he may go unshaved, stay abed too long of mornings, even break school laws. Luckily, the living out of complexes takes a much shorter time for adults than for children.' (p. 25).

In summary, congregating like-minded teachers is a potentially powerful strategy to address teacher attrition. It offers a sense of community, more opportunities for collaboration and mentorship, and a reinforced professional identity. With particular attention to privacy, agency, and self-expression, it offers teachers support they lack sequestered in private classrooms.

Hypothesis: Differentiated Classrooms

Ambassador Fellow with the US Department of Education Megan Power (2019) wrote: “The role of a teacher today is shifting. No longer is the focus of good teaching mainly on delivering content. Rather, a good modern teacher is a designer of experiences” (para. 17). Could the physical learning environment find a higher purpose by supporting teachers, not just with their own development and identity, but in presenting powerful learning experiences?

When teachers are congregated in hives with like-minded peers, classrooms are liberated from conformity. They may be differentiated to more powerfully support teachers in presenting impactful learning experiences. This is the exciting corollary to addressing teacher attrition with physical Communities of Practice: not only are teachers better supported, but students may now benefit from a far more visceral variety of activities in school. Woodman (2016) has already shown that spatial flexibility is an unfulfilled promise: teachers do not rearrange classrooms to offer a diversity of learning experiences. A variety of permanent classroom layouts offers a more reliable way to diversify pedagogy and engage students.

What might these classrooms become in order to better engage students? What can the environment even offer education? The physical environment contributes the conditions (affordances, avoidances, arrangements, allusions, ambiance) for the following learning experiences:

Immersion: to engage all the senses in a supportive environment as biology may be taught out in the wilderness.

Inquiry: to support the quest for information, ideas, opportunities or possibilities.

Inspiration: to offer problems in need of solutions, situations begging improvement, ideas seeking development, and desires inviting fulfillment. To tantalize with possible futures.

Instruction: to efficiently convey a curriculum.

Interaction: to arrange individuals synergistically, with particular attention to critical, empathic, and generative listening.

Introspection: to reinforce creativity, self-awareness, and strength of will with contemplation.

Invention: to tinker, experiment, play, deconstruct, reconstruct, and fabricate in order to reinforce the habits of original thought and effort.

Consider also:

Itinerant elements: elements that move, energizing with surprise, change, and the new.

Intersections: spaces with multiple functions to save cost and enhance meaning.

Context: the space outside of a school building: wilderness, park, field, garden, and community.

Instead of trying tepidly to do it all, spaces that specialize will more powerfully engage students. They would help teachers to deliver more visceral, more memorable learning experiences.

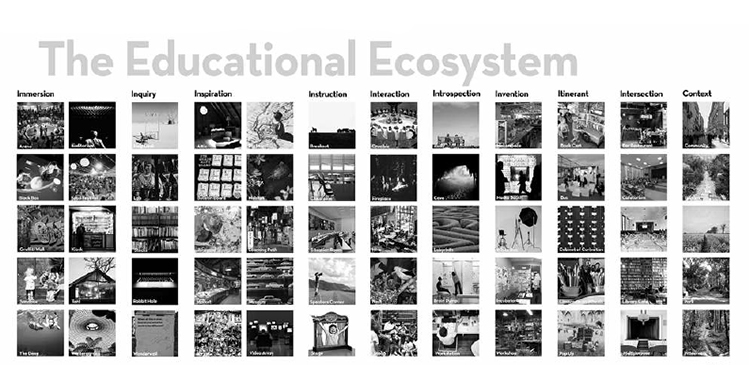

Starting with the spatially-reinforced learning experiences identified above, The Educational Ecosystem offers archetypes for what existing school spaces can become.

Figure 2: Archetypes of the Educational Ecosystem.

When four history teachers or four fifth-grade teachers move their desks to a hive, their four classrooms can each be uniquely configured to offer four completely different learning experiences. The opportunity to engage students is thereby enhanced, as is the chance to make learning more visceral and sticky. See here for a detailed explanation of each archetype.

School typologies abound: Lancaster’s 500 student classrooms, Bendix and Neufert’s Waldschule, the one-room schools of the American Expansion, Montessori’s and Steiner’s domestic workshops, School Construction Systems Development’s open-plan schools, Educational Facilities Lab’s thematic suites, Alexander’s (1977) Pattern Language, Rusch’s Mobile Open Classroom (MOBOC), Moore and Lackney’s (1994) 27 patterns, the “houses” of the (1996) School of Environmental Studies, Thornburg’s (2004) “primordial learning spaces”, Fisher’s (2005) typology of settings, Fielding and Nair’s (2005) 20 learning modalities and 25 design patterns, Dovey and Fisher’s (2014) “teaching/learning clusters”, the Learning Studios model of (2018) Canyon View High School, the community in Illich’s (1970) “deschooling” and Holt’s (1977) “unschooling”, Outward Bound’s Wilderness, and the spacelessness of Massive Open Online Courses, Kahn Academy, and edX are all examples. The Ecosystem proposed here embraces and learns from all of these models.

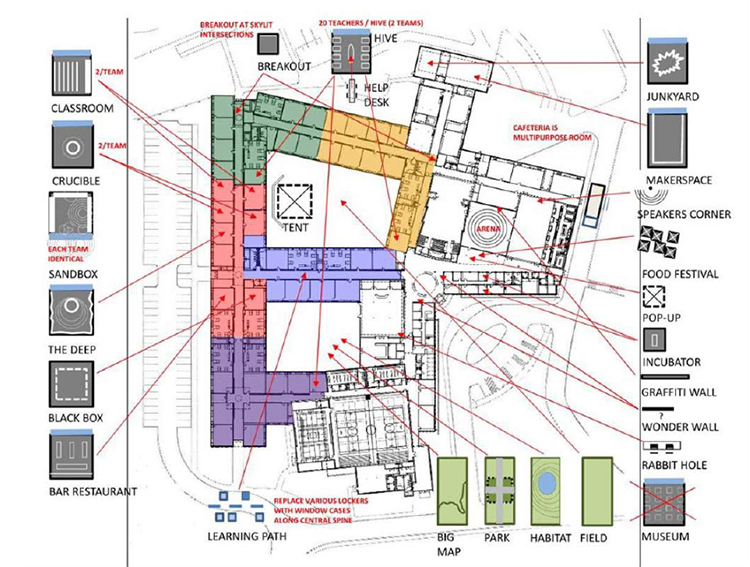

To demonstrate the potential impact, here is a transformation of an American junior high school organized into teams of 250 students, without demolishing walls:

Figure 3: Modifications to an existing school offered by the Educational Ecosystem.

Clearly, some archetypes more easily conform to existing classrooms, some to public spaces, and some to the space outside. This exercise demonstrated that finding space for teacher hives may be challenging. This issue is less salient to a school with empty classrooms, but more poignant to a fully populated school. Several spatial, scheduling, and hybrid strategies emerged to address a lack of space. Most important to the present argument is the visceral, visible enrichment of an existing school through the application of the Educational Ecosystem.

Conclusion

Schools all over the world present as monocultures of identical classrooms with only modest differentiation for unique subjects. In the United States, teacher attrition and student disengagement invite the question: what can be done to make school more supportive and engaging? Research suggests that schools take responsibility for the academic performance but also the emotional experience of their occupants. Proposed here is an approach to enriching the school environment in order to offer teachers the support they need and students the diversity of experiences more likely to keep them engaged. For both new and existing schools, this approach transforms this very expensive asset, their buildings, from a passive container into an activated pedagogic tool.

Roel Krabbendam, B.Arch M.Ed AIA LEED AP, is a registered architect in the State of Arizona, USA, a doctoral candidate at Fielding Graduate University, and the author of the 2018 book school, which explored the relationship between learning experiences and learning environments. He has designed and managed public school facility projects in the United States, Peru, and Algeria. His work may be found at www.futureofschools.com, and he welcomes correspondence at [email protected].

References

Alexander, C., Ishikawa, S., & Silverstein, M. (1977). A pattern language: Towns, buildings, construction. Oxford University Press.

Arnup, J., & T. Bowles. (2016). Should I stay or should I go? Resilience as a protective factor for teachers' intention to leave the profession. Australian Journal of Education, 60(3), 229–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004944116667620

Arroyo-Romano, J., & Benigno, S. (2016). The ethical teacher in a high-stakes testing environment. Journal of Studies in Education, 6(2), 1-19. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318399745_The_Ethical_Teacher_in_a_High- Stakes_Testing_Environment

Astleitner, H. (2000). Designing emotionally sound instruction: The FEASP-approach. Instructional Science, 28(3), 169–198. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1003893915778

Belenardo, S. J. (2001, October). Practices and conditions that lead to a sense of community in middle schools. NASSP Bulletin, 85(627), 33-45. https://journals-sagepub- com.fgul.idm.oclc.org/doi/pdf/10.1177/019263650108562704

Brown, D. N., & Settoducato, L. (2019, Winter/Spring). Caring for your community of practice: Collective responses to burnout. LOEX Quarterly, 45(4), 10-12. https://commons.emich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1346&context=loexquarterly

California School Climate, Health and Learning Survey System. (2021). California Secondary School Climate Report Card 2020-21. https://calschls.org/docs/sample_secondary_hs_scrc_2021.pdf

Carlson, J., & Thomas, G. (2006). Burnout among prison caseworkers and corrections officers. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 43, 19-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J076v43n03_02

CASEL. (2020). Our work. https://casel.org/our-work/

Dovey, K., & Fisher, K. (2014). Designing for adaptation: The school as socio-spatial assemblage. The Journal of Architecture, 19(1), 43–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602 365.2014.88237 6.

Farenga, P. (n. d.). What is deschooling about? Growing Without Schooling. https://www.johnholtgws.com/pats-blog/what-is-deschooling-about

Fisher, K. (2005, March 15). Linking pedagogy and space: Proposed planning principles. Department of Education and Training (Victoria). https://www.education.vic.gov.au/documents/school/principals/infrastructure/pedagogyspace.pdf

Gallup, Inc. (2016). Student poll. https://www.sac.edu/research/PublishingImages/Pages/research- studies/2016%20Gallup%20Student%20Poll%20Snapshot%20Report%20Final.pdf

Gläser-Zikuda, M., Fuß, S., Laukenmann, M., Metz, K., & Randler, C. (2005, October). Promoting students' emotions and achievement-Instructional design and evaluation of the ECOLE-approach. Learning and Instruction, 15(5), 481-495. DOI: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2005.07.013

Haynes, M., Maddock, A., & Goldrick, L. (2014, July). On the path to equity: Improving the effectiveness of beginning teachers. Alliance for Excellent Education.https://all4ed.org/wp- content/uploads/2014/07/PathToEquity.pdf

Illich, I. (1970). Deschooling society. Harrow.

Ingersoll, R. M., Merrill, E., Stuckey, D., & Collins, G. (2018). Seven trends: The transformation of the teaching force–updated October 2018. CPRE Research Reports. https://repository.upenn.edu/cpre_researchreports/108

Kruse, M. (n.d.) 20 plus tips to avoid teacher burnout. [Blog entry]. Reading and Writing Haven. https://www.readingandwritinghaven.com/how-to-beat-teacher-burnout-practical-tips-to-try-today/

Laurence, G. A., Fried, Y., & Slowik, L. H. (2013). “My space”: A moderated mediation model of the effect of architectural and experienced privacy and workspace personalization on emotional exhaustion at work. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 36, 144-152.

Lave, J. (1991). Situating learning in communities of practice. In, L. B. Resnick, J. M. Levine, & S. D. Teasley (Eds.), Perspectives on socially shared cognition (pp. 63-82). American Psychological Association.

Lortie, D. (1975). Schoolteacher: A sociological study. University of Chicago Press.

Moore, G. T., & Lackney, J. A. (1994). Educational facilities for the twenty-first century: Research analysis and design patterns. Center for Architecture and Urban Planning Research, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED375514.pdf

Nair, P., & Fielding, R. (2005). The language of school design: Design patterns for 21st century schools. DesignShare.com.

Neill, A. S. (1962). Summerhill, A radical approach to education. Victor Gollancz Ltd.

Ostovar-Nameghi, S. A., & Sheikhahmadi, M. (2016). From teacher isolation to teacher collaboration: Theoretical perspectives and empirical findings. English Language Teaching, 9(5), 197-205. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1099601.pdf

Power, M. (2019, July 1). Teamwork by design. Educational Leadership, 76(9). https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/teamwork-by-design

Privette, G. (1985). Experience as a component of personality theory. Psychological Reports, 56, 263-266. https://journals-sagepub-com.fgul.idm.oclc.org/doi/epdf/10.2466/pr0.1985.56.1.263

Sutcher, L., Darling-Hammond, L., & Carver-Thomas, D. (2016, September). A coming crisis in teaching? Teacher supply, demand, and shortages in the U.S. Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/coming-crisis-teaching

Thornburg, D. D. (2004, October). Campfires in cyberspace: Primordial metaphors for learning in the 21st century. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 1(10), 1-10. https://homepages.dcc.ufmg.br/~angelo/webquests/metaforas_imagens/Campifires.pdf

Wenger-Trayner, E., & Wenger-Trayner, B. (2015, June). Introduction to communities of practice: A brief overview of the concept and its uses. https://www.wenger-trayner.com/communities-of-practice/

Woodman, K. (2016). Re-placing flexibility. In K. Fisher (Ed.), The translational design of schools (pp.51–79). Sense Publishers.