Changing the grammar of schooling post-COVID-19

Tyack and Cuban (1995) note that the ‘grammar’ for schools has changed barely a jot since Charles Dickens’ depiction of the M'Choakumchild School in Hard Times. This situation has continued well into the 21st Century. Then, a watershed moment occurs in the COVID-19 pandemic which completely changes schooling and brings a situation demanding educational change.

It has been estimated 1.5 billion students have experienced school closures due to COVID-19. Across the globe, online learning at home due to COVID-19 has become widespread. There are long-term implications for education in terms of pedagogy, curriculum, learning and assessment. In a very short time in-person schools have suddenly become a variety of different structures without any time for planning and reflection.

When students stay home

The process of students being taught remotely by teachers while the students remain at home is known internationally as distance education. Implementing an effective distance education structure for every student in a very short time is a major on-going problem and significant challenges have emerged in Australia and around the world as teachers look to find better ways to support student learning through synchronous and asynchronous learning across a range of distance learning platforms. A central difficulty is to develop a learning platform that supports an online community that has an emphasis on meaningful, authentic and interactive experiences which contribute to improved learning and student well-being.

Online learning has a range of potential positives, if these virtues can be refined and implemented in a practical manner. There are still many challenges to overcome in a bid to have teachers and parents collaborate on evidence-based solutions to difficult practicable problems. One central problem is the parent acting as teacher, because teacher expertise is seldom going to be matched by parents in a distance education setting. Teachers know how to create the conditions which motivate and invite student involvement; schools can be inviting places with positive interactions and relationships with other students; and teachers can leverage student-to-student interactions to increase student motivation and engagement. In contrast, at home a student and parent can feel a sense of isolation and it is difficult to replicate the personal interactions that occur when students are physically together when learning.

Students behave differently at school than at home. Hence the roles involved must be understood differently too. There is little research in how to make distance education by the parent as teacher more effective.

Coping with social isolation with online learning

An important consideration for teachers is the potential social isolation caused by COVID-19. Conditions for a student at home are different than a school environment. The social environment at home is the family unit, while in school it is the student’s peers. Research shows children and adolescents generally attend school because of a decisive reason—their peers. This social framework falls away with home schooling. Any successful distance education program for large groups of students must address this fundamental issue and must address social isolation when planning for and delivering online learning.

The three Rs: seeking the core of distance education

The three Rs of rules, regulation and routines persist because these give shape, form and predictability to students, teachers and parents to provide schooling and conform to the accepted grammar of schooling. The compulsory aspects of attending school such as the rituals, norms, timetables, mores and values, have provided a consistent and predictable environment, which has helped students develop focused commitment which, in turn, has made schools ‘work’. What is the replacement for this structure in distance education?

A significant consideration is the system theory of Niklas Luhmann (1984) that posited that love is the centre of the family, whereas education is at the centre of the school.

| Home | Schooling |

| Family authority | School authority |

| Family as social environment | School as social environment |

| High degree of voluntariness | High level of commitment |

| High degree of spontaneity | High level of rules and rituals |

| Love in the centre | Learning in the centre |

Home schooling brings two different institutions together and teachers developing distance education processes and material must be aware of the resulting challenges. Regardless of how we describe it - online learning home-schooling, distance education, learning at home or remote learning - there are two social structures that do not have much in common but are now forced together: the family and the school.

So, what are the characteristics of these two systems? And, what are the issues to tackle if we want to make the practice of online learning work?

The Rule of Threes

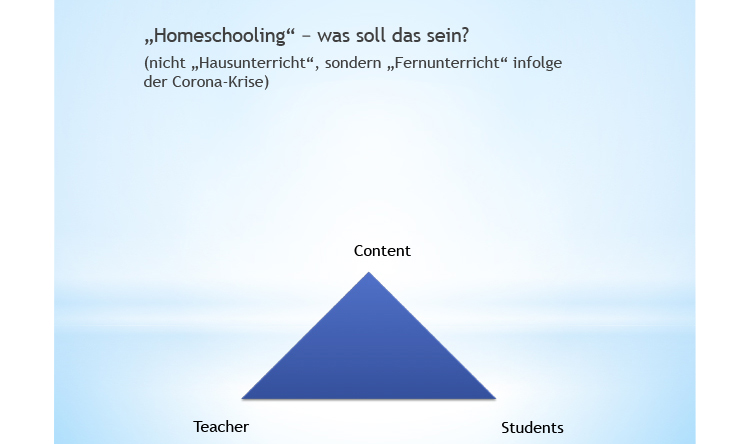

Just like rules, regulation and routines in school, another important concept that comes in threes is the heart of a school’s instructional core. The successful three-way interaction between Teacher, Content and Students is the fundamental operation of an effective school.

(cf. Hattie/Zierer, 2018):

The diagram shows a relationship level between (i) the teacher and the learner, (ii) between the learner and the subject and (iii) between the teacher and the subject. The triangle is activated when lessons take place and the relationship levels between the 'actors' become visible.

Determining where a parent acting as teacher at home fits within the concept is difficult. Is the parent required to be an agent for the message between teacher, content and student? This raises a number of important relationships for the teacher to consider and brings potential benefits and potential pitfalls with distance schooling. Firstly, there are two new relationship levels: (i) the relationship between the teacher and the parents, and (ii) and the relationship between the learner and the parents. Within certain contexts the model can expand to illustrate the relationship between the parents and the material. This is determined by the level of the content and the problems and questions confronting the learner.

Also, not all homes have the same parenting situation and that there is a wide range of carers, siblings and providers who have significant relationships and are engaged in the education of children. With a closer examination of alternatives to mother/father families, a square or other arises because there may be divergent ideas on school and schooling by each parent/caregiver. This dynamic should never be underestimated by teachers. Will the parent/caregiver be an effective teacher/motivator/mentor? Should distance lessons require any input by the parent/caregiver? These are important considerations when teachers create distance education learning activities for students.

Professor John Hattie’s Visible Learning research foregrounds the need to teach students self-regulation in the post-COVID-19 world. Hattie’s hope is we avoid a mere snap back, that we bring-back-better, and that our experience ushers in a new grammar for schools. Visible Learning research provides empirical evidence on which to build-back-better post-COVID-19. Online learning will create a change in the relationship between teachers and parents. Research by Professor Janet Clinton at the Melbourne University Graduate School of Education spells out the need to ensure that schools invite student involvement, that schools are safe, have a first-class communication strategy and that Social Emotional Learning (SEL) is embedded in school curriculum.

Ensuring that we achieve these things in online learning is a significant challenge.

In addition, COVID-19 has created a crisis in child and adolescent mental health accompanied by a not unexpected rise in substance abuse. How we deal with this situation while not in personal contact with students is problematic and it is something that requires greater attention.

In dealing with all of these issues we then face the physical environment for the learner. Some may have their own space and online equipment, while others may be much more deprived and lacking in resources and assistance at home. Equity and access become even more crucial as the gap between rich and poor is widened when students cannot share the common supportive environment of the school. In particular, digital inclusion can be very problematic for low Index of Community Socio-Educational Advantage (ICSEA) schools. Social justice issues, the fact that wealth continues to favour the rich, are exacerbated by increasing social segregation across Australia.

Where to with online learning?

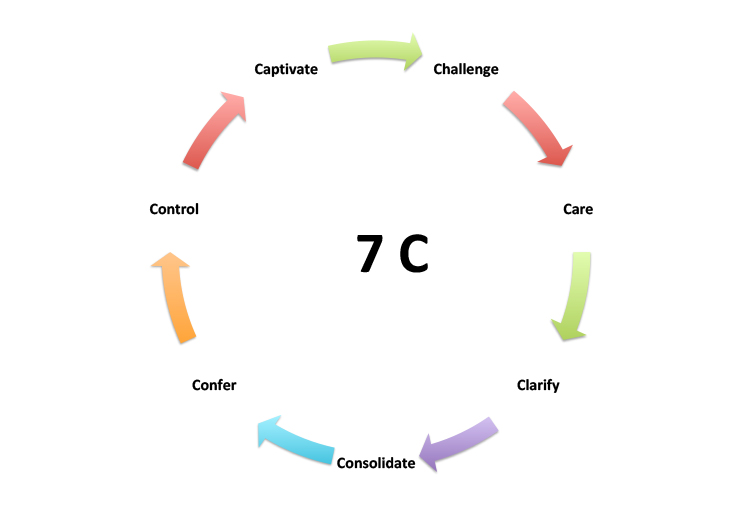

The reality is there is no toolkit to empower parents/caregivers in assisting teachers with distance education and the teachers will always remain just that, the teachers. But there is a toolkit for teachers, because empirical educational research has revealed many findings that can also be helpful in the COVID-19 crisis - for teachers and thus also for learners and parents. The 7 C’s span a network of teaching quality for the classroom and for distance education as inexorably teachers ensure the expected standards. Every C becomes an important point of connection that humanizes the experience of learning and underpins, validates and extends interpersonal experiences at the core of instruction.

- Challenge: Learning must neither be too easy nor too difficult. Both cases significantly reduce learning success. Instead, it comes down to the challenge of learning. So teachers have to be aware of challenging goals in distance learning. Blooms taxonomy with the steps remember-understand-apply-analyse-evaluate-create is a helpful toolkit for finding the perfect match between learning goals and student achievement.

- Control: Research on learning success repeatedly confirms how important classroom management is. It is a guarantee that learning will run smoothly and without distractions. Typical classroom management is no longer possible in distance learning, but there are strategies that can be transferred to distance learning. So teachers have to be aware of setting up a clear timetable and observing rules and rituals in distance learning.

- Care: Learning requires an atmosphere of confidence and trust. Without positive relationships between the learner and the teacher, but also between the learners among themselves, many efforts remain ineffective. So teachers have to be aware of encouragement, motivational attention and support in distance learning..

- Confer: Learning is a social process. Even in phases of distance learning, students are alone at first glance. A second look shows that the video, the book, the worksheet and much more is the work of a person opposite and therefore has a social character. So teachers have to be aware of encouraging and granting student judgements and using cooperative and collaborative methods in distance learning.

- Captivate: Learning is not possible without motivation. Research has shown that there are different forms of motivation: On the one hand, there is an extrinsic motivation that is quite effective, but also very short-lasting. On the other hand, an intrinsic motivation that is just as effective, but has the advantage that it has a lasting effect. In times of distance learning, it is challenging for teachers to generate and maintain this intrinsic motivation. So teachers have to be aware of developing and maintaining fascination for the subject. An important pillar here can be the context that currently concerns children and young people. During the COVID-19 crisis, learners started to think about similar questions to what adults did. Why shouldn’t this be taken up and linked to school learning content? Current questions have an intrinsic motivation and are ideally suited to talk to the learners.

- Clarify: The clearer learners are about the goals they should achieve, and the clearer the learners are made aware of what learning success should be, the more successfully they can learn. So teachers have to be aware of transparency, diverse explanations and approaches.

- Consolidate: Research results show, determining whether learners have achieved the goals is essential. Not only teachers need this information to be able to plan the next lesson, it is also important for learners to recognize what they have achieved and what they have to work on next. So teachers have to be aware of giving and receiving feedback more than ever. They do not have the everyday observations in the classroom, the conversations in the school playground and in front of the classrooms.

We can foresee that for reasons related to socio-economic situation or lack of prior personal learning some parents/caregivers may be uncomfortable or ineffective in mentoring and assisting students. In this situation the use of structured activities requiring remembering, understanding and applying information will require little input apart from support and encouragement. The ‘playing field’ is relatively level, assuming online access for activities that require only remembering, understanding and applying. Most of these activities will have an individual focus and can be done by the student alone, with support by the parent/caregiver.

Providing the opportunity for students to work online with their peers to analyse, evaluate and create is going to be the biggest challenge of an online environment. It is achievable, but there will be a seismic shift in schooling to take the teacher out of the classroom and online into each student’s home. There are challenges, but also exciting opportunities that reflect the reality of many students who spend much of their entertainment time in an online world.

Pedagogy is more important than technology as the basic understandings of teaching and learning always remain decisive and are manifested in the principles of reflective learning—the ‘grammar’ of teaching. It is universal and—indeed fundamental, that schools must invite student involvement, whether that be in-person teaching or distance education.

References

https://www.dese.gov.au/document/professor-janet-clinton-centre-program-evaluation- melbourne-graduate-school-education

Hattie, John / Zierer, Klaus (2018): 10 Mindframes for Visible Learning. Roudlegde.

Hattie, John / Zierer, Klaus (2019): Visible Learning Insights. Routledge.

Jahng, Namsook / Krug, Don / Zhang, Zuochen: Student Achievement in Online Distance Education Compared to Face-to-Face Education. https://www.eurodl.org/materials/contrib/2007/Jahng_Krug_Zhang.htm (10.05.2020)

Luhmann, Niklas (1984): Soziale Systeme. Grundriss einer allgemeinen Theorie. Frankfurt am Main

MET (2010): Learning about Teaching. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Tyack, D. B., & Cuban, L. (1995). Tinkering towards utopia: A century of public school reform, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press

Zierer, Klaus (2019): Putting learning before technology. Routledge: London.

Photo by Jimmy Chan from Pexels