Collective Teacher Efficacy: I Am Because You Are

In education, where the principal’s role is now recognised as a critical factor in schools’ achievements, schools have rarely stopped to look at the specialisation and strategies of profession coaching. In comparison to professional coaching in sport, in-school staff coaching generally presents as an amateur hour effort from well-meaning people who are still at the level of having to convince the players to make an effort.

In the last 125 years we have seen the football coaching position evolve from the best player being anointed captain-coach. Such examples include Aleck Sloan 1898, 1899, Fitzroy; Dick Wardill 1900, Melbourne; Tod Collins 1901, Essendon; Lardie Tulloch 1902, 1903, Collinwood. Furthermore, the mighty Kevin Murray who spent most of his later life as captain-coach for East Perth in the 1960s and 1970s was one of the last to carry out this dual role. While football remained an amateur sport, the coaching and on-ground captaining often remained a composite role, not unlike the role of the present-day principal. Gradually, as the game developed, there came a realisation that specialisation was a more efficacious alternative, and the captain and coaching roles had to be divided.

The final iteration of this division was the realisation that coaches come with a specific set of skills and knowledge, and teams could not afford to be left in a vulnerable state because the coach had a weakness in relation to a specific play. As one example, to address this need for specialisation, the senior coaching structure at Melbourne Football Club currently includes a senior coach; an assistant coach; a general manager, backline and forward coaches; and three associated coaches.

That is, eight coaches for a team that has fewer members than that of the staff of a mid-sized high school. In the AFL context there is a driving expectation of success, and coaches’ professional lives are short if the team does not have success - this is not the case with school leaders. For footballers, collective efficacy is a concept that is applied when team members combine to achieve the goal that is in front of their minds every day of the football season - winning the Grand Final.

In a comparative sense, the concept of collective efficacy in education has been the poor relation when compared with what we see in high profile sports, where big money, future endorsements and reputations hang on the results. There are a lot of variables that influence collective team efficacy, but the key factors of vision, and team cohesion, which Carron, Brawley, and Widmeyer (1998) defined as ‘a dynamic process which is reflected in the tendency for a group to stick together and remain united in the pursuit of its instrumental objectives and/or for the satisfaction of member affective needs’ (p. 213) remain as the mainstay. For this cohesion to endure there must be measures of success, which then excites the efficacy factor.

Efficacy: The Starting Point

The early research on school-based efficacy is now over four decades old. The pioneering work of Amor et al. (1976, p. 23) examined minority students’ reading ability in Los Angeles, and they found that ‘The more efficacious the teachers felt, the more their students advanced in reading achievement.’ The key factor in leadership and students’ learning therefore came back to high levels of self-efficacy. Self-efficacy however, is a belief in one’s own ability, rather than their actual ability, to perform a task or achieve a goal (Leithwood & Jantzi, 2008, p. 497). The essential work of schools is socio-cognitive learning, and as Goddard, Hoy and Hoy (2004, p. 3) observed there are three levels of efficacy beliefs in schools.

The first level of efficacy beliefs related to the students of which there is a growing corpus of research showing the importance of students’ self-efficacy to their learning. The second level examines teachers’ self-efficacy (Tschannen-Moran, Hoy, & Hoy, 1998). The third level is that of teachers’ collective efficacy (Donohoo, 2017; Goddard, Hoy, & Hoy, 2004).

Reeves (2008, p.4) noted that ‘The data from our studies suggests that where there is a high degree of teacher and leadership efficacy, the gains in student achievement are more than three times greater than when teachers and leaders assume that their impact on achievement is minimal’ suggesting that self-efficacy is of vital importance at the three levels in education. Similarly, the effect of the development of self-efficacy on students’ self-image and learning cannot be ignored as Gettingen’s (1999) cross-cultural, education studies in pre-unification Germany identified.

Bandura’s Model of Self-efficacy

Bandura (1977, p. 191; 1999, pp. 3-4) hypothesised that personal efficacy is based on four factors:

‘In the proposed model, expectations of personal efficacy are derived from four principal sources of information: performance accomplishments, vicarious experience, verbal persuasion, and physiological states. The more dependable the experiential sources, the greater are the changes in perceived self-efficacy.’

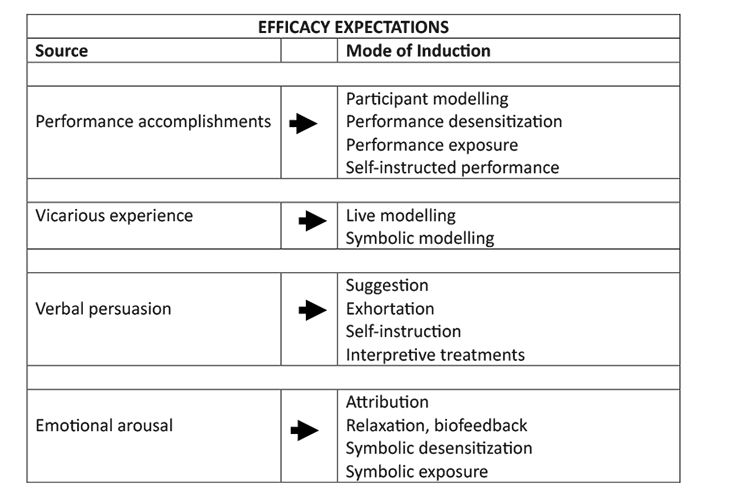

Self-efficacy is a complex mix of personal beliefs about one’s abilities. On that, Helterbran (2007, p. 12) observed, ‘Self-efficacy, the perceived belief in one’s abilities to organize and execute a learning task, also involves issues of competence and control’. Bandura’s (1977, p. 195) examination of the four sources of efficacy expectations can be seen in Table 1 (below).

Table 1 Bandura’s Four Sources of Efficacy Expectations.

Developing Bandura’s (1977, p. 195) four input model of self-efficacy, Betz (2007, p. 409) observed, ‘It is these learning experiences - performance accomplishments, vicarious learning, social persuasion, and physiological arousal - that therefore should guide the development of efficacy-theory-based interventions’.

Self-efficacy is of critical importance in the development of human agency, and Bandura (1982) found:

‘Perceived self-efficacy helps to account for such diverse phenomena as changes in coping behavior produced by different modes of influence, level of physiological stress reactions, self-regulation of refractory behavior, resignation and despondency to failure experiences, self-debilitating effects of proxy control and illusory inefficaciousness, achievement strivings, growth of intrinsic interest, and career pursuits.’ (p. 122).

Importantly, students’ self-efficacy is a key determinant in occupational choice: ‘Children's perceived efficacy rather than their actual academic achievement is the key determinant of their perceived occupational self-efficacy and preferred choice of work-life’ (Bandura, Barbaranelli, Caprara, & Pastorelli, 2001, p. 187).

Moving from Self-efficacy to Collective Teacher Efficacy (CTE)

The era of the singular hero-leader has finished (Senge, 2000; West-Burnham, 2009). Organisational theory now acknowledges the need for collective leadership, and consequently, as Watson, Chemers and Preiser (2001) quoting Bandura, observed that in regard to efficacy, ‘Collective efficacy represents a group’s shared belief in its conjoint capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce given levels of attainments’. Bandura (1999, p. 34) warned that some writers have equated self-efficacy with individualism. This is not the case, and he noted that, ‘a high sense of personal efficacy contributes just as importantly to group directedness as to self-directedness’ (p. 34). In education, several studies have documented a strong link between perceived collective efficacy and differences in student achievement among schools (Bandura, 1993; Goddard, 2001; Goddard et al., 2004):

‘Bandura demonstrated that the effect of perceived collective efficacy on student achievement was stronger than the direct link between SES and student achievement. Similarly, Goddard and his colleagues (2004) have shown that, even after controlling for students’ prior achievement, race/ethnicity, SES, and gender, collective efficacy beliefs have stronger effects on student achievement than student race or SES. Teachers’ beliefs about the collective capability of their faculty vary greatly among schools and are strongly linked to student achievement’ (Goddard et al., 2004, p. 7).

In examining cross-cultural perspectives on self and collective efficacy, Gettingen (1999) compared East and West Germany, before unification. In East Germany, students submitted to teacher and peer evaluations in front of the class collective, and also in “learning conferences” in which the student underwent public evaluation (pp. 158-159). In contrast, students in West Germany were protected by privacy considerations. On re-unification, as a group, the less able East Germans suffered the greatest loss of self-efficacy because they had been protected in the authoritarian, East German state. Gettingen (1999) reported that, ‘Earley found that the assessed level of self-efficacy was a highly valid predictor of performance for both types of work conditions (i.e., individualistic vs. collectivistic) for both types of people (i.e., individualistic vs. collectivistic). This latter finding further supports the assumption that self-efficacy’s effect on performance is universal’ (p. 171).

Rachelle Eells (2011) in her doctoral research, refocussed attention on collective teacher efficacy (CTE), which she redefined as, ‘… an emergent group level property referring to the perception of teachers in a school the faculty as a whole will have a positive effect on the students’ (Goddard, Hoy, & Woolfolk-Hoy, 2000). All of the research worked around the intra-school development of CTE, but we believe that this concept has strong inter-school possibilities that have not yet been recognised.

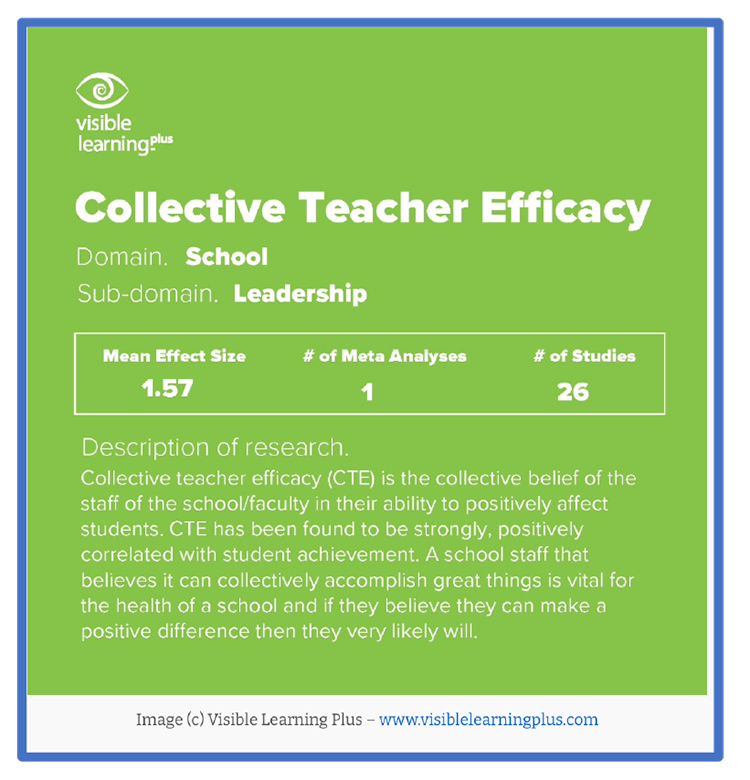

A force majeure in the recognition of CTE, Jenni Donohoo (2017), is acknowledged, and her book ’Collective Efficacy’ that complemented John Hattie’s meta-analytical research refocussed school improvement activities. Hattie’s (2018) updated list of factors that influence student achievement can be seen in Figure 1. It is important to note that CTE topped the Effect Size list (d = 1.57) and self-efficacy (of students) ranked 11th.

Figure 1 Hattie’s (2018) List of Factors related to Student Achievement

Discussion

It is fortunate that educational research can benefit from the spin-off of research into collective efficacy in other organisational structures such as team building in sport and business enterprises. For example, in a team situation Katz-Navon and Erez (2005, p. 439) noted that the change from self-efficacy to a collective efficacy may occur in two stages:

‘… first, individuals shift their reference from the individual to the group level when they evaluate team efficacy. Second, the agreement among all team members elevates the construct itself to the group level. Thus, collective-efficacy reflects the shared beliefs of the group members in their group’s capabilities to mobilize the motivation, cognitive resources, and courses of action needed to produce given levels of attainments on a specific task.’

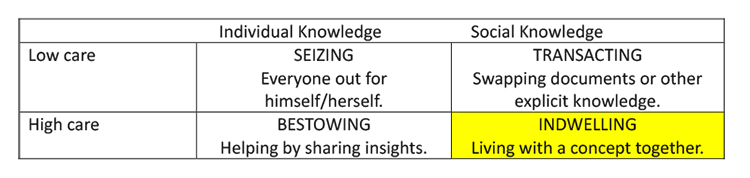

What happens in sporting teams also occurs in school teaching teams, as collective efforts are initiated to address whole-school goals, and nurtured by care. At this point it is worthwhile looking at the knowledge and skill creation in CTE, within the often-unacknowledged culture of purposeful care. Importantly, Von Krogh, Ichijo, & Nonaka (2000) demonstrated the importance of care in knowledge creation, which helps to conceptualise the quality of CTE in schools.

Table 2 Knowledge creation when care is high or low. [Von Krogh, Ichijo, & Nonaka (2000, p. 55].

The point that is being powerfully made, is that the Indwelling level of school culture can show that the CTE culture is embedded in teaching operations.

So, what does the coaching comparison with high-level sport tell us in relation to CTE in schools?

First, the principal cannot be captain-coach, and he/she needs to be the general manager who oversees other coaches.

Second, specific coaching expertise and responsibility needs to be developed in the school staff. Secondary schools already have a structure in place, while primary schools are developing Phase Leaders, or subject leaders. Growing teacher leaders facilitates CTE development.

Third, the vision, goals, and agreement over what good teaching looks like needs to be developed by the whole staff, and playbooks (Boyd, Lehr & MacNeill, 2024) are essential because new staff who are recruited need to know the rules of the game.

Fourth, top of the range data needs to be made available to the teams so that the goals are meaningful, data informed, and the students and parents know they are getting a good educational deal.

A winning AFL team requires a collective effort from all involved - an effort that requires the coach, and the accompanying coaching team, to provide the support and guidance that moves winning beliefs to an actual reality. Collective teacher efficacy needs to be supported and nurtured in the same way within a school context, through the collective efforts of the principal and his/her leadership team in developing each teacher’s skills in such a way that they complement and strengthen the work of their peers. It will be through these inspired, collective endeavours that school communities can ultimately achieve high levels of success, both now and in the future.

References

Amor, D., Conry-Oseguera, P., Cox, M., King, N., McDonnell, L., Pascal, A., et al. (1976). Analysis of the school preferred reading program in selected Los Angeles minority schools. RAND.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191-215.

Bandura, A. (1982, February). Self-efficacy: Mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2), 122-147.

Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of self regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 248-287.

Bandura, A. (1999). Exercise of personal and collective efficacy in changing societies. In A. Bandura (Ed.), Self efficacy in changing societies (pp. 1-45). Cambridge University Press.

Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G.V., & Pastorelli, C. (2001, January). Self-efficacy beliefs as shapers of children's aspirations and career trajectories. Child Development, 72(1), 187-206.

Betz, N.E. (2007, November). Career self-efficacy: Exemplary recent research and emerging directions. Journal of Career Assessment, 15(4), 403-422.

Boyd, R., Lehr, R., & MacNeill, N. (2024). The Instructional Playbook+: A bespoke model for pedagogic improvement in schools. Education Today. https://www.educationtoday.com.au/news-detail/The-Instructional-Pl-6153

Carron, A. V., Brawley, L. R., & Widmeyer, W. N. (1998). The measurement of cohesiveness in sport groups. In J. L. Duda (Ed.), Advances in sport and exercise psychology measurement (pp. 213–226). Fitness Information Technology.

Chemers, M.M., Watson, C.B., & May, S.T. (2000, March). Dispositional affect and leadership effectiveness: A comparison of self-esteem, optimism, and efficacy. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 26(3), 267-277.

Donohoo, J. (2017). Collective efficacy: How educators’ beliefs impact on student learning. Corwin.

Eells, R.J. (2011). Meta-Analysis of the Relationship Between Collective Teacher Efficacy and Student Achievement [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Loyola. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/133

Gettingen, G. (1999). Cross-cultural perspectives on self-efficacy. In A. Bandura (Ed.), Self efficacy in changing societies (pp. 149-176). Cambridge University Press.

Goddard, R. D., Hoy, W. K., & Woolfolk Hoy, A. (2000). Collective teacher efficacy: Its meaning, measure, and impact on student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 37 (2), 479-507.

Goddard, R. D. (2001). Collective efficacy: A neglected construct in the study of schools and student achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(3), 467–476.

Goddard, R.D., Hoy, W.K., & Hoy, A.W. (2004, April). Collective efficacy beliefs: Theoretical developments, empirical evidence, and future directions. Educational Researcher, 33(3), 3–13.

Helterbran, V.R. (2007). Informal learners: Mid-life learners forging a learning philosophy. The Journal of Educational Thought, 41(1), 7-26.

Katz-Navon, T.Y., & Erez, M. (2005, August). When collective and self-efficacy affect team performance: The role of task interdependence. Small Group Research, 36(4), 437-465.

Kruger, M. (2009, April). The Big Five of school leadership competences in the Netherlands. School Leadership and Management, 29(2), 109-127.

Leithwood, K., & Jantzi, D. (2008, October). Linking leadership to student learning: The contributions of leader efficacy. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(4), 496-528.

Leithwood, K., Mascall, B., Strauss, T., Sacks, R. Memon, N., & Yashkina, A. (2007). Distributing leadership to make schools smarter: Taking the ego out of the system. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 6(1), 37–67.

McCormick, M.J. (2001). Leadership effectiveness: Applying Social Cognitive Theory. The Journal of Leadership Studies, 8(1), 22-33.to Leadership

Office of Principal Preparation and Development (n.d.). The Chicago Public Schools: CPS Principal Competencies and Success Factors. http://www.oppdcps.com/downloads/CPS_Principal_Competencies_Success_Factors.pdf

Reeves, D.B. (2008, September). Leadership and learning. Monograph of the Australian Council for Educational Leaders, 43.

Senge, P. (2000). The leadership of profound change. Statistical and Process Controls Press. http://www.spcpress.com/pdf/Senge.pdf

Tschannen-Moran, M., Hoy, A.W., & Hoy, W.K. (1998, Summer). Teacher efficacy: Its meaning and measure. Review of Educational Research, 68(2); 202-248.

Von Krogh, G., Ichijo, K., & Nonaka, I. (2000). Enabling knowledge creation: How to unlock the mystery of tacit knowledge and release the power of innovation. Oxford University Press.

Wahlstrom, K.L., & Louis, K.S. (2008, October). How teachers experience principal leadership: The roles of professional community, trust, efficacy, and shared responsibility. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(4), 458-495.

Watson, C.B., Chemers, M.M., & Preiser, N. (2001, August). Collective efficacy: A multilevel analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 27(8), 1057-1068.