Controlling behaviours: Gaslighting strategies that are developed at a school age

Introduction

The three-act play, ‘Gas Light’, is a murder mystery set in the late 1800s, in London. In this play, the brow-beaten wife sees a ghostly intervention in the dimming in her room's gaslight. She doesn't realise that her murderous husband, is convincing her that she is going mad, so he can recover some hidden rubies.

The term Gaslighting, in its original form, was related to the psychological abuse that was applied in a marital or intimate relationship, as portrayed in the play and the subsequent movie. Gaslighting has now become a buzz word that is broadly applied to psychological abuse in any relationship, and it is now being picked up in movies, television reality shows, sporting associations and in American politics. In the 2016 film, ‘The Girl on the Train’, the confused Rachel, is manipulated by her ex-husband who convinces her that her memories are incorrect. These patterns of power abuse have been termed coercive control by Stark (2007) to describe gender-based oppression in abusive relationships.

In the Australian television version of the show, Married at First Sight (MAFS 2021), the relationship expert, John Aitken, remarks to a male participant: “That behaviour is gaslighting, it is toxic and is something that needs to stop.” For many viewers this was the first time that they had heard the term applied to a specific form of abuse. In American politics, the term was being broadly applied to a range of ex-president Trump's actions.

Gaslighting can also be considered a sociological phenomenon specifically in a school context. Paige Sweet (2019) asserts the sociological nature of gaslighting is based in the social inequalities that are exploited by the abuser and develops the theory that although gaslighting involves psychological dynamics it is ‘the social characteristics that actually give gaslighting its power’ (p. 851).

What is interesting is that gaslighting strategies do not simply appear in adulthood, because they are learned during children's school years in all of the social contexts in which they participate. In schools, students are socialised into a broader community than they experience in their homes, and at this time they learn important inter-personal skills and values. When their relationships become challenging or go awry, the gaslighting behaviours of control and manipulation are often exhibited, but they are seen as bullying by busy school staff.

While there are variations in the use of gaslighting, Anthony Watts (2020) identified 11 warning signs of gaslighting strategies:

- They tell blatant lies

- They deny they ever said something, even though you have proof

- They use what is near and dear to you as ammunition

- They wear you down over time

- Their actions do not match their words

- They throw in positive reinforcement to confuse you

- They know confusion weakens people

- They project (accuse you of misdemeanours)

- They try to align people against you

- They tell you or others that you are crazy

- They tell you everyone else is a liar.

These strategies are applied in a context where there is a controlling, relational power imbalance, which underwrites the potential damage of all these strategies.

Gaslighting and psychological abuse

Erin Hightower (2017, p. v) in her doctoral research noted that gaslighting is a form of subtle abuse: ‘This study reveals gaslighting as a subtle and covert type of emotional and psychological abuse. Gaslighting involves a varying cluster of manipulations used to undermine an intended target person’s reality and mental stability.’ She reported one of Calef and Weinshel's examples where a man created fear in his family by driving in a fast and erratic manner while portraying a calm, nonchalant demeanour:

‘His calm nonchalant ignoring of fear and terror, while telling his family they overreact and denying their experience is all subtle. He regularly created a sense of panic and fear, which is overt, then dismissed, denied, and diminished their experiences, which is subtle. He used ridicule and denial, overt and subtle respectively, never physically harming any of them, which is also a subtle tactic especially when coupled with fear, and the gaslighted wife considered herself the sick one.’ (p. 95)

It is incorrect to view all gaslighting as subtle and covert as illustrated in the original play, the gaslighter (Mr Manningham) was by no means subtle or covert. In fact, Mr Manningham's overt acts began as covert and subtle and ended up as blatant bullying.

Controlling behaviours and gaslighting

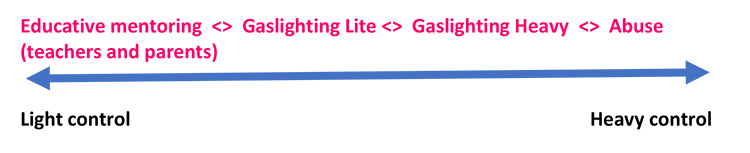

Gaslighting fits within the domain of controlling behaviours, and controlling behaviours can be used for good or damaging purposes. In Figure 1 (below) gaslighting is just one strategy for controlling another person, or group of people. And, it is hypothesized that gradations of control can be seen in the modelling of gaslighting strategies depending on the gaslighter's ultimate intent. The end point of the controlling behaviours continuum is always defined as abuse for independent adults and children.

Figure 1: Controlling Behaviours and Gaslighting

Cindy Lamothe (2019) developed what she believed were the 12 indicators of controlling personalities which show high correlation with Watts's gaslighting list (above):

- They make you think everything’s your fault

- They criticize you all the time

- They don’t want you to see the people you love

- They keep score

- They gaslight you

- They create drama

- They intimidate you

- They’re moody

- They don’t take ‘no’ for an answer

- They’re unreasonably jealous

- They try to change you

- They may show abusive behaviour.

Gaslighting in Lamothe's list is but one example of controlling behaviour.

What do we see at school?

Children develop social behaviours from watching adult interactions and relationships in their homes and the wider world; but they also grow these inter-personal relationships in their own lives. Power laden relationships between students are a feature in the school context and it is possible to identify full-blown gaslighting, and the precursors of gaslighting in the actions of school students.

Case studies 1: Dating

In the origins of the term gaslighting, many authors believed that the practice of gaslighting was confined to "intimate" relationships, as seen in the eponymous play and movie. However, the application of the term is now more broadly applied. In an excellent study of controlling behaviours in American secondary students' dating experiences Elias-Lambert, Black and Chigbu (2014, p. 841) found:

‘Over three-fourths of the participants perpetrated and were victimized by controlling behaviors in their dating relationships. Youth used emotional/verbal and dominance/isolation forms of controlling behaviors. More youth were victimized by dominance/isolation controlling behaviors than emotional/verbal controlling behaviors. Gender and age differences emerged when evaluating the type of controlling behaviors youth used.’

While the term gaslighting does not appear in this article, the precursor behaviours on the control continuum are clearly identifiable. The examples of emotional/verbal controlling in this research are closely related to less focussed examples of gaslighting.

Case study 2: Queen bees and wannabees

As students progress through the pre-pubescent stage of development social relationships outside the family circle become more important, and students start to learn their social roles. In our (Harley & MacNeill, 2017) article ‘Queen bees, wannabees, relational aggression, and inappropriate socialisation’ the Queen Bee actively and covertly controlled the primary school members of the group in relation to aspects of their appearance and their thoughts, and also their roles within the group. Putting aside the gender tag on a Queen Bee role for a minute, it is not a great leap of faith to see the portability of the inappropriate social roles from the school ground to adult gaslighting and social controlling.

Case study 3

Sociologist Paige Sweet, (2019) studies domestic abuse and asserts that gaslighting is deeply rooted in “societal structure and social inequalities and that women are more likely to experience gaslighting due to these inequalities” (p. 870). Crucial to the context of schools, Sweet identifies key social mechanisms which gaslighting tactics create ‘surreality’. These include, ‘associating victims’ thoughts, speech, and actions with feminized irrationality, exploiting intersecting inequalities related to race and nationality, and using victims’ lack of institutional credibility against them’ (p. 870).

There can be little argument on the impact of abusive relationships and gaslighting on the victims. Rodriguez, G (2020) lists the myriad of vulnerable mental health issues that experiencing gaslighting can lead to such as ‘anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress, poor self-esteem, co-dependency.’

Educators and parents have a responsibility to their children to educate students about mental health and healthy interpersonal relationships. Gaslighting in student relationships offers an opportunity to shine a light on gaslighting tactics and work towards redressing under-recognised forms of power at play.

What can we do?

From a school perspective, we need to address the dyadic aspects of all gas lighting algorithms. The gas lighters need specific programs to address this type of bullying, and the gaslightees need specific help in developing more assertive strategies to deal with this problem that is not going to go away. While many gaslighting precursor strategies go unrecognised in primary schools, they are more prevalent in secondary schools where individuals start to develop personal relationships with others outside their family circles.

Elias-Lambert, Black and Chigbu (2014) in their American study stressed the importance of seeking help in relation to controlling behaviours in dating/ close types of relationships and they found that ‘The large majority of youth (89%) in this study were willing to seek help from others when confronted with controlling behaviours’ (p. 858). As we saw in Harley and MacNeill's (2017) article, the case-by-case attention to counselling with the other involved students developed an educational solution for all parties.

In the big picture however, there is clearly a need for educational guidance in this area of social and psychological development so that the danger signs of controlling behaviours and gaslighting can be recognised by students.

Recognising that someone is gaslighting you is an important first step. The three-pronged graphic known as the Y chart is an excellent strategy to capture student voice and ownership in characterising what gaslighting ‘looks like, sounds like and feels like.’ This strategy brings the often-covert gaslighting strategies to the surface and describes expectations and strategies that can be put into place by potential victims.

In high-risk occupations, the employees are taught IAs (Immediate Actions) and other drills, such as Dr ABCD in life saving, which are intended to save lives. We would argue that Year 5 and Year 6 students need to be exposed to a range of complex situations that they will experience in life (including domestic violence), and learn drills that will address the situations.

References

Elias-Lambert, N., Black, B.M., & Chigbu, K.U. (2014). Controlling behaviors in middle school youth’s dating relationships: Reactions and help-seeking behaviors. Journal of Early Adolescence, 34(7), 841-865.

Harley, V., & MacNeill, N. (2017, November). Queen bees, wannabees, relational aggression, and inappropriate socialisation. Australian Educational Leader, 39(4), 26-28.

Hightower, E. (2017). An exploratory study of personality factors related to psychological abuse and gaslighting. Unpublished doctoral thesis. William James College: Florida.

Lamothe, C. (2019, November 21). 12 signs of a controlling personality. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/controlling-people

Press, Sweet, P. (2019). The Sociology of Gaslighting. American Sociological Review, 84(5) 851–875.

Rodriguez, G. (2020). Gaslighting: How to Recognize it and What to Say When it Happens. https://www.thepsychologygroup.com. The Psychology Group: Fort Lauderdale, TX.

Stark, Evan. (2007). Coercive Control: How Men Entrap Women in Personal Life. New York: Oxford University.

Watts, A. (2020, March 14). The 11 gaslighting characteristics of the climate debate. Psychology Today. Chico: United States.

Photo by cottonbro from Pexels