Direct Instruction, Explicit Teaching, Mastery Learning and Good Teaching

Our starting point in addressing teaching and learning is to acknowledge that there are a multitude of teaching strategies in use, and as Silcox and MacNeill (2021, p. 111) noted, teachers should utilise teaching strategies from their repertoire of strategies that best fit the learning task. This task is not dissimilar to Tiger Woods's selection of the appropriate club from the 14 golf sticks in his golf bag during a tournament. While the explicit teaching strategies are ranked as very efficient in teaching for the mastery of essential knowledge and skills, definitional issues often cloud teachers' understandings of these pedagogic tasks.

With the misinformation surrounding Direct Instruction (DI) and Explicit Direct Instruction (EDI), mixed with a constellation of near synonyms, Teacher Directed Mastery Learning (TDML) now exists in a world of confusion that aids those who cannot recognise the pedagogic efficacy of these strategies. A colleague remarked that Explicit Instruction is now in a position similar to the lay persons' use of the term the flu, which covers the common cold, a sniffle, sinus problems and pneumonia. Explicit instruction has probably existed since groups of people learned to communicate.

"Don't roll in that fire if you are going to sleep because…."

"Always light the fires at night when the lions are close to the camp because…."

Direct instruction underwrites important information necessary for individuals' health and safety. In the modern world, military pedagogy is a prime example of this, where the learning content can be a matter of life and death. The military argues that if the soldiers have not learned the essential lesson content, then the teacher has failed in his/her task (see Johns & MacNeill, 2020).

This aphorism is expanded by Jean Stockard (2021), who noted:

‘It is important to note that the onus for learning is not on the student, but on the instruction. If students do not learn it is because the instruction has not been appropriate. That is, the instruction has to be effective. In addition, instruction must be efficient. It should be designed so that time isn’t wasted, so that students learn as much as they can in the shortest amount of time. And the development of the programs needs to be research-based.’

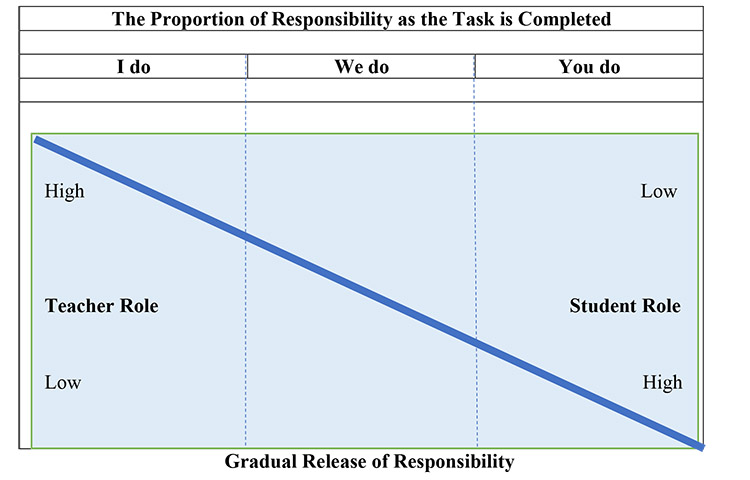

Gradual Release of Responsibility Learning (I do, We do, You do)

This is what the "I do- We do- You do" approach looks like: The teacher explicitly models how to use a protractor in maths. Then, the teacher shows the students how to align the protractor on a printed example, and checks for understanding. Next, students work together in small groups to practise aligning the protractor, while the teacher does over-the-shoulder checking. Finally, students work independently on five printed examples, and the teacher moves around checking for understanding.

While this three-part development of instruction has probably existed since families taught their children the essential survival skills in pre-historic times, the modern mythology is now attributing this instructional approach to Pearson and Gallagher (1983) who developed the landmark framework of the gradual release of responsibility (GRR),

Pearson and Gallagher (1983, p. 337) studied the murky situation of reading comprehension that existed at that time, and they developed this description of the teaching, role and the gradual release of responsibility in the teaching act:

Figure 1 The Gradual Release of Responsibility (adapted from Pearson & Gallagher, 1983)

Interestingly, the Pearson and Gallagher (1983) link this to what Rosenshine called "guided practice".

Situated Learning: Apprenticeships

Lave and Wenger (1996), in their examination of Communities of Practice, specifically studied apprenticeships and they developed the concept of situated learning, which has implications for the study of early applications of explicit teaching and learning. It is interesting to consider school learning as a situated "apprenticeship" for meaningful citizenship, in which a mixture of explicit and social learning takes place. However, that is another story.

Background: The Pedagogic Wars

The pedagogic wars are still alive and well as some schools promote research backed pedagogic decisions that are often contrasted to the euphemistically named approaches (balanced learning, whole-child development, learn through play) decisions influenced by unstated ego-investment, ideology, and often not knowing any better.

It is interesting that this war gets very personal and classroom teachers are often in conflict with the dark forces that dismiss scientific measurement. Megan Watkins (2007) observed that teacher directed learning to many Australian teachers, "is something akin to ‘abusive pedagogy’ that stifles students’ learning" (p. 303).

Bearing this situation in mind, let's clarify these linked concepts.

Unravelling the Threads

Explicit teaching is founded on four beliefs:

- The teacher knows more than the student

- It is the teacher's job to teach the student skills for a fulfilling life in society

- Some teaching is essential for the student's safety

- If the student fails to learn, then the teacher has failed to teach.

(a) Direct Instruction. Direct Instruction (DI) was developed by Dr Siegfried "Zig" Engelmann in the 1960s and it combines well-crafted explicit instruction pedagogy, again this is scripted. The only DI program that we use in both of our schools, are Spelling Mastery and EMM/JEMM (Rhonda Farkota's Elementary Maths Mastery), which have proved to be very effective.

(b) Explicit Direct Instruction. Explicit Direct Instruction (EDI) was developed by John Hollingsworth and Dr Silvia Ybarra in the early 2000s. It is based on educational theory, brain research, direct instruction and classroom observations. It combines a set of instructional practices to produce what they describe as “well-crafted and well-delivered lessons” This instructional framework involves the development of highly detailed and scripted lessons that follow a predetermined sequence. It is explicit in that it breaks the lesson down to its smallest chunks but it is direct in that it follows a script. Sitting within this are a number of structures that they have developed, these include:

- Engagement norms and,

- Lesson Delivery (TAPPLE)

The EDI Dataworks program is what underpins Noel Pearson “Good to Great Program”.

(c) direct instruction (lower case). The term direct instruction (lowercase) was used by Dr Barak Rosenshine in his 1976 teacher effectiveness research to describe a set of teaching practices found to be significantly related to increasing student achievement. Many programs have been developed based on key pedagogic principles and techniques of the DI program, often collectively referred to as direct instruction or explicit instruction. At West Beechboro Primary the school uses Rosenshine’s principles of an effective lesson, essentially breaking the actual teaching down into its smallest chunks. Sitting within this is the "I do", "We do", "You do" that was pulled from Pearson and Gallagher (1983) and further refined while working with John Fleming and what he espoused in ‘Towards a moving school (2007). As well as the concepts of surface learning and deep learning that were taken from Hattie’s Visible Learning.

While there are many versions of Rosenshine's (1987) principles of direct instruction, this list is focussed on classroom teaching:

- Begin a lesson with a short statement of goals

- Begin with a short review of previous, prerequisite learning

- Present new material in small steps with student practice after each step

- Give clear and detailed instructions and explanations

- Provide a high level of active practice for all students

- Guide students during initial practice

- Ask a large number of questions, check for student understanding, and obtain responses from all students

- Provide systematic feedback and corrections

- Obtain a student success rate of 80 percent or higher during initial practice

- Provide explicit instruction for seatwork exercises, and, where possible, monitor and help students during seat-work

- Provide for spaced review and testing.

Importantly, Rosenshine (1983, p. 337) stated that … "Overlearning basic skills is also necessary for higher cognitive processing", and, this underwrites our beliefs in Daily Reviews.

It was these principles that Dr Lorraine Hammond utilised, along elements of both Explicit Instruction, Explicit Direct Instruction and Direct Instruction, to support the Kimberley Schools Project, a collaboration between the Department of Education, Catholic Education Western Australia, the Association of Independent Schools Western Australia and the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development in improving literacy outcomes for students within this region. This work, also supported by Emeritus Professor Bill Louden, established a common pedagogical framework for all schools involved in the project. Louden stated that “This lower-variation approach to teaching reflects the kind of thinking summarised in Rosenshine’s (2012) research-based principles of instruction” (2018, p. 10).

(d) Instructional Theory into Practice (ITIP). Madeline Hunter developed a model of explicit teaching that consisted of seven components:

1 Objectives

2 Standards

3 Anticipatory set

4 Teaching (input, modelling, checking for understanding)

5 Guided practice/monitoring

6 Closure

7 Independent practice

Madeline Hunter's work is now considered of historical interest, but one quote worth remembering is: "Practice does not make perfect- it makes permanent" (Hunter, 2004, p. 97), which fits perfectly with Rosenshine's concept of over-learning.

(e) Military Instruction (MI). In Johns and MacNeill's (2020) paper, military instruction is explained and it makes the point that for knowledge and skills that are regarded as essential, failure to learn is not an option. The Australian Army text, “Land Warfare Procedures G-7-1-2: The Instructor’s Handbook” (2017) is a manual that clearly sets out lesson planning, lesson delivery, and lesson assessment, and for military instructors EDI means Explain, Demonstrate, and Imitate, which is a variation on: I do; we do; you do. During the lesson the instructor must constantly check for understanding (CFU).

The lesson plan describes what a good lesson would look like in any classroom: Lesson objectives, prior knowledge, motivation, introduction, statement of relevance, body of lesson with teaching points, CFU, explanation, demonstration, imitation, test for learning, give praise, dismiss.

A colleague noted that he learned more about teaching in qualifying as a military instructor than he did in four years at university!

(f) Explicit Instruction: John Fleming. John Fleming sprang to our attention when he turned around Bellfield Primary School, a low SEI/ICSEA school in Melbourne. Fleming was a do-er and thinker, and in turning around Bellfield he realised that what he had done with his staff was transportable to other schools. The four pillars of school improvement that drove the change at Bellfield were:

1 Teacher directed learning

2 Explicit instruction (EI)

3 Moving student learning from short-term to long-term memory

4 Effective relationships between teachers and students (Fleming & Kleinhenz, 2007, p. 48-49).

Fleming was enticed from Bellfield, to Haileybury, and onto an Australia-wide audience for his practical thoughts on teaching and learning, where he has been able to re-skill thousands of teachers and school leaders.

| Characteristics | DI | EDI | di | MI | ITIP | EI |

| Scripted lesson | x | |||||

| Over-learning/Warmups | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Mastery of essential knowledge | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Lesson goals stated | x | x | x | |||

| I do; You do; We do | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Chunking learning/ ZPD | x | x | x | |||

| DI= Engelmann; EDI= Hollingsworth & Ybarra; di= Rosenshine; MI= Military Instruction; EI= Fleming | ||||||

Table 1 Comparison of the Models of Explicit Teaching and Direct Instruction

A better way to go: Clever Learning

At the end of the day there is not an educator reading this discussion document (written while doing students' mid-year reports) who does not want to be able to deliver the most effective and engaging learning experiences for their students. The research shows that the most effective way to teach essential cognitive knowledge and skills is using explicit teaching strategies, however, there are other factors at play in lesson delivery. We believe that teachers should use the most effective strategies that promote students' learning, and this does not mean everything is explicit or direct instruction. As school leaders we need to make certain that multiple factors are in place to ensure student learning, student engagement, success and happiness. That challenge faces us every day and we need to get it right for the students!

References

Ashman, G. (2021). The power of explicit teaching and direct instruction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Fleming, J., & Kleinhenz, E. (2007). Towards a moving school: Developing a professional learning performance culture. Camberwell, Victoria, ACER Press.

Hunter, R. (2004). Madeline Hunter's Mastery Teaching: Increasing instructional effectiveness in Elementary and secondary schools. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Johns, B., & MacNeill, N. (2020, March 27). No Failure Learning in Military Instruction. Education Today. https://www.educationtoday.com.au/news-detail/No-failure-learning-in-military-instruction-4849

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1996). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Louden, B. (2018). Evidence-based approaches to school improvement: The Kimberley Schools Project. https://research.acer.edu.au/research_conference/RC2018/12august/3/

Pearson, P.D., & Gallagher, M.C. (1983). The instruction of reading comprehension. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 8, 317-344.

Rosenshine, B. (1983, March). Teaching functions in instructional programs. The Elementary School Journal, 83(4), 335-351.

Rosenshine, B. (1987, May-June). Explicit teaching and teacher training. Journal of Teacher Education, 38(3), 34-36. https://doi.org/10.1177/002248718703800308

Silcox, S., & MacNeill, N. (2021). Leading school renewal. Abington, Oxford: Routledge.

Stockard, J. (2021). Building a more effective, equitable, and compassionate educational system: The role of Direct Instruction. Perspectives on Behavior Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40614-021-00287-x

Watkins, M. (2007). Disparate bodies: The role of the teacher in contemporary pedagogic practice. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 28(6), 767–781.