Enhancing Clarkson Community High School's Performance Culture in 2019

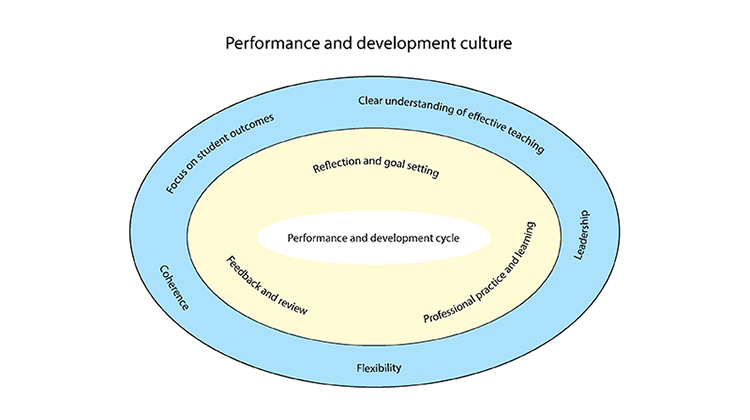

The question of how to move a teacher from their current level of effectiveness to a higher level of effectiveness is a challenging question and there is not one simple solution. Australian schools have generally been stronger on the development part than the appraisal part; however, an effective approach to performance building must balance both. At Clarkson CHS, we support teachers’ classroom performance through tailored feedback and provide targeted professional support that addresses each individual teacher’s needs. Enhancing Clarkson Community High School’s Performance Culture in 2019 explores how we can continue to build an authentic performance culture through harnessing achievement data analysis, engaging with peer observation processes and truly listening to the student voice. The article also attends to the important role leadership traits play when building or enhancing a performance culture. Throughout the paper, I make consistent reference to the Australian Teacher Performance and Development Framework (the Framework) Figure 1 which provides a convenient outline of the critical factors for creating a performance and development culture in schools.

What is a performance culture?

An authentic performance culture sees all teachers take collective responsibility for high quality teaching and sustained poor performance by any individual teacher is addressed ethically and professionally. This involves creating a set of norms where there is enough trust, ownership and openness for all teachers to consider how their teaching might be improved. School leaders can sharpen the focus on teacher performance through acquiring skills to create a performance culture throughout the school.

The National College for Teaching and Leadership in the UK explains the dominant factor in securing consistent and sustainable high- performance culture is the personal performance of the middle leader and her or his focus on the performance of the team and the individuals in that team. Modelling high performance seems to be one of the most compelling and credible leadership approaches available to any leader. There seems little doubt that the language and behaviour of middle leaders are also significant variables in creating a high-performance culture.

A basket of methods

There are multiple ways to create an environment for professional growth and for the assessment of individual teacher’s effectiveness. Different sources of evidence have been identified and preferenced in schools but essentially no method is without flaws. Each of the evidence sources on its own provides only partial information about how well a teacher is teaching. Various combinations used in a system designed in collaboration with teachers and modified in the course of implementation, can provide a sound basis for providing feedback on a teacher’s classroom performance.

The Grattan Institute’s (2012) report acknowledges that each method provides incomplete information about how well a teacher is teaching.

The report lists the following sources of evidence for teacher appraisal:

- Student performance data

2. Peer classroom observations

3. Line manager classroom observations - Student feedback

5. Teacher self-assessment

6. Parent feedback

7. External classroom observation - 360-degree feedback

Evaluating our impact at Clarkson

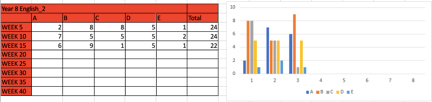

At the core of a high-performance culture is a process about how teachers will be involved in evaluating their own teaching and the impact it is having on their students. The Framework’s first factor that contributes to a performance and development culture is the focus on student outcomes. Kane (2013) notes that, ‘If we want students to learn more, teachers must become students of their own teaching’. Highly Accomplished teachers work with colleagues to use data from student assessments to evaluate learning and teaching, identify interventions and modify teaching practice (AITSL Standards 2017). The CCHS English and HaSS Learning Area engage with a school-wide five-week data review process to capture timely information about student progress. In Term One, I created a single ‘anywhere’ Microsoft OneDrive excel data document for team members to examine their classes’ progress and the grade composition of other classes. My Year 8_2 English class data from the OneDrive document (Figure 2), represents an example of how I and the team can reflect on student performance collectively.

Figure 2

Figure 2

This approach has proven to be successful with HaSS teachers approaching their English counterparts and vice versa to ‘face the data’. The formal and informal dialogue to discuss our impact on classroom practice enables us to intervene quicker and collectively find solutions to learning deficits. If there are five more A grades in my English class than the HaSS class with the same students, my HaSS colleague and I need to examine assessment rigour, differentiation practices, moderation and student profiles. Staff at Clarkson CHS employ the 5 Week Data Review to examine their impact and use data, not opinion to communicate practice.

De-privatising practice

School leaders’ subjective assessments of teachers are often effective predictors of student achievement. Jacob and Lefgren (2005) found that ‘...assessments of teachers predict future student achievement significantly better than teacher experience, education, or actual compensation....”. As a Head of Learning Area conducting classroom observations, I need to acknowledge the timing and frequency, level of trust and my own skills in giving feedback. The AISTL website has proved invaluable to support my own skillset. When implementing a process of classroom observations, it is important to consider that teachers will not accept a performance appraisal system that is seen to ‘manage’ them. The lesson learned from the 2014 introduction of a new teacher appraisal scheme in Victorian public schools provides us with a case study for continual reference. ‘Rather than being done with and for teachers, many measures advocated and being hastily and poorly implemented in the quest to improve teaching and learning, are essentially being done to teachers and without their involvement, almost guaranteeing resistance, minimal compliance and inefficiency’ (Stephen Dinham, 2013).

In Implementing a Performance and Development Framework, Jensen and Reichl (2012) note:

‘Appraising others’ performance, being appraised, providing feedback – none of these things are easy. They come naturally to some, but to the majority they are learned skills. To most in the teaching profession they are foreign and intimidating prospects.’ (P.11)

In Term Two, we launched a whole school peer observation initiative to supplement formal line manager classroom observations that take place at the beginning and end of each year. Peer observation involves teachers observing and providing feedback to other teachers. The success of this as a method for providing teachers with information about their teaching depends on the school climate, clarity of purpose, level of trust and a host of other factors relating to the way the system is implemented. Peer observation is an important and effective way of changing the culture of a school from one where staff operate in isolation or in ‘silos’ to a more open and collaborative one. In our recent General Staff Meetings, the peer observation groups shared their de-privatisation stories with other groups to inspire staff to engage further with the process. The project has supported the sharing of practice and built awareness about the impact of my colleagues’ own teaching and developed a clear understanding of effective teaching in order to affect change.

All perspectives are valuable

‘The average student knows effective teaching when he or she experiences it’

(MET 2012, p.1)

Clarkson’s school ethos is underpinned by Invitational Education; a practice to create, maintain and enhance human environments that invite people to realise their potential. Democrative practice underpins the theory to promotes the idea that everyone in an organisation has a perspective that is valuable and needs to be incorporated into schoolwide discourse.

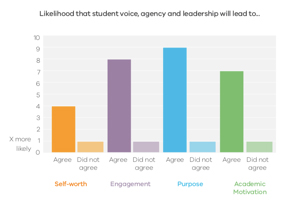

Research findings indicate that student voice, agency and leadership have a positive impact on self-worth, engagement, purpose and academic motivation (Quaglia, 2016), which contribute to improved student learning outcomes (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Figure 3

Clarkson has built a culture where teachers and students work together and student voice is heard and respected. Teachers and school leaders receive valuable feedback that can lead to improved teaching practice and contribute to school improvement. Students feel more positive and connected to their school and see themselves as learners and better understand their learning growth. Our school’s Student Council led by Teacher of Media Jasmita Jeshani and Dr Steve Laing exemplifies democratic behaviors through the collection of evidence about teacher performance and student sentiment toward learning. The MET Project Policy and Practice Summary (2012) confirms student survey results correlate as strongly with predictions about student learning as classroom observations do, and that they prove a more reliable measure than observations alone. The student council should acknowledge that students can report on teachers with a high degree of reliability, however the validity of the survey results depends on the instrument used (Goe, 2007).

Some commentators like Goe claim that student perception surveys are more likely to measure teacher popularity than effectiveness. The evidence, however, suggests that a properly constructed survey instrument can provide valid and reliable information as one part of a suite of measures. The more frequent the surveys, the more useful the information. The age of students also affects how the surveys should be designed. In particular, it is important to note that primary students tend to rate teachers more generously than older students.

Trust and leadership traits

While trust in leadership is significant, we cannot underestimate the evidence about the importance of trust between teachers. If teachers don’t trust their colleagues, the atmosphere required for successful collaborative work will not exist (Harris et al,2013).

Hattie (2012) believes that trust is essential to the effective implementation of the 138 ‘influences’ on learning and explains that ‘professional discussions (amongst teachers) must be conducted in an atmosphere of trust more than an atmosphere of accountability’.

He gives particular attention to the association of trust and willingness to make errors and treat them as opportunities to learn. He believes that to get better teachers need to be comfortable about making errors and trust is essential for this.

‘...In order for us to build the high-performance culture, leadership must cultivate the environment for trust.’

Leaders who demonstrate personal integrity, commitment and honesty are reported to develop stronger and more trusting relationships with teachers. (Brewster & Railsback, 2003). Their view is that school leaders working in a culture of trust empower teachers and draw out the best in them.

Successful school leaders improve student outcomes in their school through who they are – their values, virtues, dispositions, attributes and competencies – as well as what they do in terms of the strategies they select and the ways in which they adapt their leadership practices to their unique context. The AITSL publications Australian Professional Standard for Principals and the Leadership Profiles (2014) and Leading for impact: Australian guidelines for school leadership development (2017) refer to the following attributes under the leadership requirement category Personal qualities, social and interpersonal skills:

- Emotional intelligence

- Empathy

- Resilience

- Personal wellbeing

- Self-management

- Self-awareness

- Trustworthiness

- Environmental awareness

- Social awareness

- Cognitive capacity

- Openness to feedback

In order for our school to enhance our performance culture, our leaders must exhibit attributes that will enhance levels of trust across the school. The Principal Performance and Improvement Tool has building productive relationships as one of the six key leadership practices of effective principals. The literature suggests we can strengthen school culture by listening to staff concerns; encouraging staff to show initiative; expressing interest and care for staff; having honest two-way conversations; showing respect for all members of the community; and being ‘out and about’ in the school and at school events.

Conclusion

Excellent workplaces make sure that every individual receives continuous feedback on their performance and areas for improvement, both positive and negative. These workplaces also prioritise data over opinion.

As we strive to implement an exemplary performance and development culture across our school, it is particularly important that school and team leaders are trained in how to appraise and provide feedback and to have difficult performance conversations where that is required.

When we establish a peer observation culture, school leaders need to work with staff to agree on protocols and procedures and involve staff in the planning process. School leaders must support staff to provide improvement focused feedback that is based on evidence and early career teachers to learn from more experienced teachers.

Young people who find their own voice in supportive school environments are more likely to develop a confident voice, a capacity to act in the world, and a willingness to lead others. By empowering students, we enhance student engagement and enrich their participation in the classroom, school and community. We help students to ‘own’ their learning and development, and create a positive climate for learning (Amplify, 2018).

Finally, in order to enhance our performance and development processes at Clarkson where teachers access continuous feedback, we must consider the school climate.

The leadership and culture at the school level determines whether we adherence to policies and run processes to improve outcomes. Hattie (2012) reinforces the notion, “Without a level of trust, teachers will ‘close ranks’, ‘put up shutters’ and retreat to the old and tried methods behind a closed classroom door”.

Leaders at Clarkson CHS have an obligation to empower teachers and draw out the best of them. Their personal integrity, commitment and honesty establish stronger and more trusting relationships amongst teachers and sustain a school climate where excellence can flourish.

References

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (2017) Leading for impact: Australian guidelines for school leadership development.

Department of Education and Training Melbourne (2018), Amplify: Empowering students through voice, agency and leadership

Dinham S. (2011) Teaching and learning, leadership and professional learning for school improvement. Presentation 17803, University of Melbourne.

Hattie, J. (2012) Visible learning for teachers, Routledge, London and New York.

Harris J., Caldwell B., & Longmuir F. (2013) Literature review: A culture of trust enhances performance. Australian Institute of Teaching and School Leadership, Melbourne, Victoria.

Jensen B. and Reichl J. (2012) Implementing a performance and development framework, Grattan Institute, Melbourne, Victoria.

Kane T. (2013) Measures of Effective Teaching Project Releases Final Research Report. Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Jacob, Brian A. and Lars Lefgren (2005). Principals as Agents: Subjective Performance Measurement in Education Working paper.

Marshall G., Cole C. and Zbar V. (2012) Teacher Performance and development in Australia: A mapping and analysis of current practice Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership. Melbourne, Victoria.

MET Project Policy and Practice Summary (2012), Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

www.nationalcollege.org.uk. 2019. Building and sustaining a culture of high performance: the role of the senior leader. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.nationalcollege.org.uk/cm-mc-ewsm-cs-secondary.pdf. [Accessed 13 June 2019].