Evening the Playing Field - Schools as a Network

Schools are often competitive, they compete at sport, compete for staff, high marks for Year 12 exams and smart new buildings are always a source of one upmanship. However, changing that way of thinking and sharing resources and facilities might make a lot of sense.

After all, once the day is done many science labs, art studios and gymnasiums lie empty and could be put to use, either by the wider community or other schools that lack those facilities. Hoarding is inefficient and maybe a little bit selfish.

Architecture firm Hayball Principal Dr Fiona Young says, “Generally, schools tend to be independent entities, their sites surrounded by fences keeping students in and the rest of the world out. During term time, each school houses the bustle of students and teachers as they all navigate their schedules, within an array of spaces such as classrooms, etc. Come evening, the weekend, or during the roughly 12 weeks of vacation period each year, these spaces sit empty. If we consider space utilisation across the whole year, then this makes school facilities pretty inefficient.

“What would it be like if rather than schools as siloed entities, they worked as a network, drawing upon a shared pool of resources either within a school site or a separate location central to all?

“Perhaps schools (and students) didn’t all have to start and finish at the same time, but greater scheduling variation allowed more effective use and higher utilisation of a whole network of educational facilities each day and across the year. And what if these ‘learning spaces’ supported life-long learning, enabling others from the community to offer teaching or to come to also learn within these spaces?”

As the population grows and, especially in the cities, land becomes increasingly scarce, issues of cost, equity and sustainability in providing adequate school facilities for all students arise.

“Perhaps a key to addressing these issues is by thinking about how schools can work as a network, sharing resources and facilities so that every student gets more, improving educational opportunities for all.

“There is great potential in rethinking toward a more collective educational landscape, however it requires a paradigm shift from how school has been done to how it could evolve. A more networked and connected version of school brings the energy and bustle from within the school to the community. As a starting point it would require a new way to think about timetabling, transport, and security,” says Dr Young.

The reality is that while the idea has been around for some time, a functioning network of schools is still some way off. That said, Hayball have been working with school systems in both Sydney and Brisbane to explore ideas around shared STEAM hubs between and across a cluster of schools.

And there are some interesting ideas emerging such as City as School, which is currently in Beta version, an online platform that connects young adult learners ages 14-19 with inspirational teachers and mentors to develop real-world skills and solve local and global challenges.

This draws from the purely online model of Outschool, which has been in operation for eight years, and offers both online and in-person classes for learners ages 14-19 years old.

There’s an increasing array of examples of schools as community hubs, opening facilities to others in the community beyond their own students.

An inspiring example is SEK – Santa Isabel in Madrid, where there are multiple learning pathways identified for students across the city. While this is an example of only one school, you can imagine other schools in the vicinity also drawing upon the facilities and resources of the city.

SEK-Santa Isabel is a case study as part of the Harvard Project Zero Learning Outside-In project.

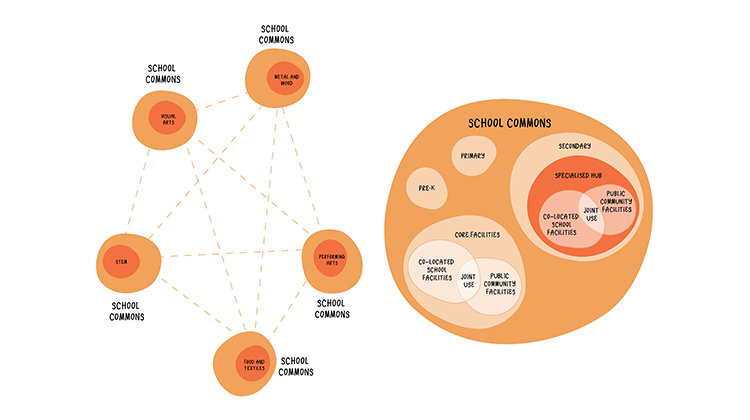

In conceptualising a network of schools, it makes sense to strategise and clarify what each school offers or needs and how they might complement each other. For example, each school may choose to elevate the identity of a particular area to become a centre of excellence in the network. See Team Hyphen’s “Designing a Network of Schools” page 54 of the Schools for Community Guide.

The network could be reflected in the built environment through an architectural or graphic (branding) language across the schools involved giving clear signals of the networked facilities in the community. This could be applied to school buildings, shared facilities in the community, or community facilities (e.g. galleries, museums etc) offering learning programs for students. It could also form part of wayfinding on shared pathways connecting learning hubs.

Logistical issues and movement between the schools and their facilities could be overcome with the creation of safe shared pathways for biking and walking with clear wayfinding signage on paths/signposts. There might also be shuttle buses or trains (like how an airport skytrain connects a limited series of stops) to connect learning hubs.

Organising a network of schools means timetables would need to shift to allow time to connect between hubs. Rather than moving every hour to a new classroom, perhaps students would go to a hub for a half or full day for an immersive program within a dedicated specialist facility.

Logistics would need to consider the stage and age of students, for example, older students who have demonstrated the ability for independent mobility would have access to a wider range of facilities outside of ‘school’ than younger students who may only be able to access external facilities as part of a school excursion with their teachers and parents.

Schools such as Ao Tawhiti in Christchurch, NZ, located right in the heart of the CBD already vet their students in this way. Students need to demonstrate maturity in independent mobility to have the freedom to leave the school to access other places for learning during the day. For instance, some students attend university for some courses.

A network of schools involves the surrounding community as part of a learning landscape. Schools may offer both programs and facilities to the community and vice versa. In today’s world, where there is increasing need to be constantly upskilling one’s knowledge base and expertise to meet the challenges of a rapidly changing world, a networked model of education makes this easily accessible.

For community organisations and businesses who form part of this network, the intersection with learners can enliven workplaces and enhance staff knowledge. For students, the opportunity for their learning to be more connected to the world ‘outside the school gates’ is enhanced.

“Taking the idea of a networked community further, our AfterSchool proposition recognised the opportunity for intergenerational learning and connection. Often, older retired community members are isolated and lack connection with others and sense of purpose,” says Dr Young.

“AfterSchool proposed educational ‘volunteers’ who once vetted as suitable, would be able to support students to navigate between learning hubs and/or support teachers as part of learning programs. Some libraries around the world are recognising the wealth of history and knowledge older members of the community have and have formed ‘Living Libraries’ where these people can be ‘gotten out’ by library visitors to talk to and to learn from.”

Diagram by Team Hyphen – Danica Cruz, Rachel Liang and Sophie Busch.