Leadership Values and Beliefs: A Journey of School Community Discovery

When a new principal arrives in a school, the resident staff will often spend some time trying to determine the new leader's values and beliefs about learning and teaching. Viewing the process from outside the organisation, what the observer sees is an exercise in the gradual release of those values and beliefs, in terms of what the leader thinks is appropriate at that time, within the school’s context. Imagine a large jigsaw puzzle with 200 written belief pieces and no picture cues. Typically, that is what the staff are faced with as they come to understand the amalgam of belief and value clues the principal models to the school community. Interestingly, some of the jigsaw pieces can present these messages in different forms as this allows the leaders to make contextual adjustments to their leadership values list. A pre-emptive statement of values and beliefs from the new school leaders would give the staff an immediate understanding of how the school's administration will operate instead of waiting for events to occur that requires a piecemeal demonstration of what actions, beliefs and values are now legal tender in the school.

Creating a List of Values and Beliefs

There is no personal, educational equivalent of the Apostles' Creed, declaring the personal values and beliefs to which the leaders and staff are committed in public schools:

I believe in God,

the Father almighty,

Creator of heaven and earth….

As Australian school leaders personally become more experienced in a variety of school contexts, their values may evolve; however, their personal belief system will expand with the greater understandings born of those experiences. For example, with the moral value of "a fair go for all," the value statement will stay fairly constant throughout a leader's life. However, the variety of beliefs that are generated from this value will change as the principal is provided with opportunities to lead in schools with perhaps a low ICSEA, or in rural and remote schools. Consequently, school leaders may have to fine-tune their beliefs system in the way they juggle the twin concepts of equality and equity.

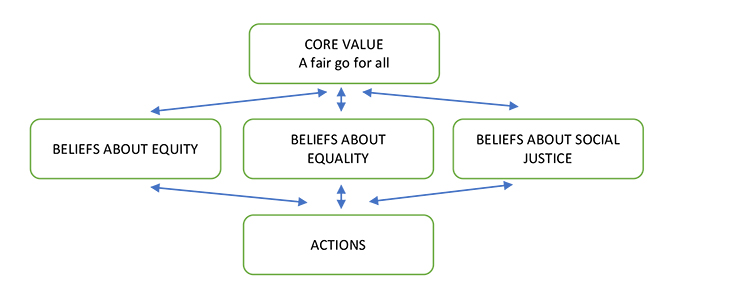

In Figure 1 we have shown the relationship between values, beliefs and actions, and we argue that these three aspects of all actions are linked by two-way inter-actions, because human beings are sentient, and rational. So, actions (not just traumatic actions) can also influence a person's beliefs and values. If this were not the case then individuals' values would remain unchanging over their life-times; which is illogical.

Figure 1. Values and Associated Beliefs

Figure 1. Values and Associated Beliefs

In our book, 'Leading School Renewal' (Silcox & MacNeill, 2021), we stopped and analysed why we had taken certain courses of action dealing with in-school issues. It was this after-action analysis that helped us enumerate our beliefs and to pin them to the page. School staff are in the same situation as they examine why the school leaders have taken a certain action, and they then can rightly ask is this consistent with previous statements. Because these beliefs are often not publicised, the shortcoming in school leadership is that staff have to analyse a leader’s actions and then play the game: "Guess what drove me to take this course of action?"

We listed 46 beliefs in the book, and each one was developed as a logical extension of the theme of the situation being described. We identified six themes into which the beliefs fall:

B1. Leading Schools (Vision setting, emotional intelligence, communication etc…)

B2. Value-added leadership

B3. Teaching and Accountability (Profiling, catalytic etc…)

B4. Enhancing Student Learning

B5. Looking to the future (Empowering schools etc…)

B6. The Moral High Ground

Let's take B6 "The high moral ground" based on the value of doing good for our school community, and as a thematic example and from this we can identify the following beliefs:

- A leadership disposition that values and encourages fairness, openness, honesty, loyalty and integrity in relationships will facilitate the creation of a learning and teaching culture that is purposeful and empowering and subsequently renewal ready.

- Re-culturing a school requires a clearly defined and well-communicated vision of an agreed future, which generates commitment, not compliance.

- The enabling of schools to be empowered with the authority to make decisions that reflect the needs and aspirations of the individual school and the local community will enhance community perceptions about the value of learning and teaching.

- When school leaders put the priority on adding value to the schools’ learning and teaching culture, improved student achievement outcomes follow.

- The commitment to excellent public schooling underwrites our entrenched beliefs in democracy, equity and social mobility.

- School leaders need to forecast what values, skills and knowledge their students will need in a society 13 years in the future. And, we all need to be cognisant of what the international testing is telling us about where we sit in what will be the new order.

Not surprisingly, many of the listed beliefs fit into more than one belief theme, and there is a degree of overlap.

Moving Personal Values and Beliefs to Underwrite School Culture

In any organisation a stated value or belief is a guide to action. This is particularly so in a school context where values both stated and unstated, and continually modelled by leadership, inform the fundamental beliefs that offer a guide to staff on how they are expected to behave and act. Consequently, a school’s leadership needs to ensure that the overtly articulated and implied values are clearly understood and then appropriately actioned by all staff. The values and beliefs that a school holds help to contribute to its image within the context of the community which it serves.

By way of example, Catholic schools have both stated and implied values that are understood in communities. Belmonte, Cranston and Limerick (2006) observed inherited beliefs underwriting Catholic schooling:

‘For the Catholic school community, values and ideals have been intrinsically bound over the centuries by the religious traditions of the Catholic Church. As an inherited ideology, it has served as a firm framework for the building of an authentic educational and faith community.’

And, these inherited beliefs go even further, as Brinig and Garnett (2012, p. 33) observed in Chicago: 'Our findings – that the presence of a Catholic school in a police beat appears to suppress crime,' which even influences the status of a community and property prices.

In an interview, Anthony Bryk (2008), who studied Catholic schools in the United States, made two important points about the values and culture of Catholic schools:

Firstly, ‘What really jumped out at us were the relational resources that existed and how powerful those were, particularly in the context of educating disadvantaged students’ (p. 137). Secondly, he made the point about choice on the part of staff and also the school community. He noted, ‘So voluntary association is about choice, but ‘choice’ frames the phenomena around a market metaphor. When you think about the formation of these social relationships, the fact that everybody chooses to associate with one another, this creates important social resources for school improvement…’ (p. 137). The religious cultural values colour every aspect of what happens in these schools.

Catholic school provide just one example of overt values-based schooling. This religious-cultural theme that most private schools promote is seen as a strong point within the wider community context in attracting student enrolments.

In the public school system, the secular display of school mottos, vision and mission statements require close reading because these schools, generally, do not have the brand recognition of their well-known private school counterparts. And, the value bases constantly change as the public-school leadership transits through the regime of promotions and transfers. In contrast, in private schools, the school and its community owns the values, and the resulting ambient culture.

Promoting School and Personal Values and Beliefs

Every school community needs to be taken through a process by the leadership to generate a statement of the values and beliefs that are seen as essential in underpinning its learning and teaching culture. Unfortunately, this is often hidden in compliance related and rarely read mission and vision statements which are left-overs from the 1980s when there was an infatuation with strategic and business plans. A more succinct way of promoting what a school stands for can be seen in Values Promises. Ken Wallace (n.d.) stated:

'A sales value promise comprises everything you communicate to your customer prior to their purchase of your product or service. Likewise, a service value promise comprises everything you convey to your customer after their purchase. These promises tell your customers how they should do business with you in order to get what they want in the way of value (competitive pricing, customized service, complete integrity in information provided, a quick and efficient sales process, etc.).’

The useful thing about Values Promises when applied to the education sector is that they provide a ready measure against which to evaluate learning and teaching service delivery. Also, this statement established an important relationship algorithm with each of the stakeholders in the school community, which can be seen in Community Compacts. Furthermore, the values statement is a guide to action for the staff and to the community.

Conclusions

Values and beliefs about teaching and learning will not eventuate through the mere commands of leadership rhetoric, they must be instilled, discussed and believed in at every level of a school as a learning organisation, with all staff as a collective taking pride in what they are doing. Only then will a school become a respected education organisation. We think that Value Promises is a better strategy to inform staff and the school community what they can expect in a school. Such a strategy will help school communities to develop and take ownership of the values and culture of the school, and judge staff against their commitment to that values-promises based culture.

References

Belmonte, A., Cranston, N., & Limerick, B. (2006). Voices of Catholic school lay principals: Promoting a Catholic character and culture in schools in an era of change. Paper presented at the AARE conference, Adelaide. https://www.aare.edu.au/data/publications/2006/bel06236.pdf

Brinig, M.F., & Garnett, N.S. (2012, Winter). Catholic Schools, Charter Schools, and Urban Neighborhoods. The University of Chicago Law Review, 79(1), 31-57.

Bryk, A. (2008, December). Catholic schools, Catholic education, and Catholic educational research: A conversation with Anthony Bryk. Catholic Education: A Journal of Inquiry and Practice, 12(2), 135–147.

Silcox, S., & MacNeill, N. (2021). Leading school renewal. Routledge.

Wallace, K. (n.d.) Crafting your sales and service value promise. CSM. https://www.customerservicemanager.com/crafting-your-sales-and-service-value-promises/

Appendix 1. Our Personal Beliefs About Education, Leadership and School Change (from 'Leading School Renewal').

1. The sustainable reculturing of a school requires a proven renewal paradigm of change that can be activated by the school leader.

2. The improvement of students’ learning outcomes often requires a significant change in a school’s pedagogical culture.

3. A leadership disposition that values and encourages fairness, openness, honesty, loyalty and integrity in relationships will facilitate the creation of a learning and teaching culture that is purposeful and empowering and subsequently renewal ready.

4. Principal efficacy is an essential factor that underwrites successful and sustainable pedagogic change.

5. Re-culturing a school requires a clearly defined and well-communicated vision of an agreed future, which generates commitment, not compliance.

6. Principals’ self-efficacy beliefs, in association with their personal behavioural dispositions, impact directly on school improvement, effectiveness and renewal endeavours.

7. The enabling of schools to be empowered with the authority to make decisions that reflect the needs and aspirations of the individual school and the local community will enhance community perceptions about the value of learning and teaching.

8. That one template of schooling does fit all school situations because there is never one right design or one structure that will suit every school in a variety of situations.

9. The professional relationships that teachers establish with their students form the bases of inclusive pedagogy.

10. A measure of good leadership is the accommodation of the multitude of situational factors that impact significantly on school leadership strategies and decision making.

11. A toxic school culture, if not excised by the principal, will derail any attempts to initiate school curriculum or cultural change.

12. Weak school leaders tend to create and foster a more sycophantic staff culture.

13. School change to be effective and sustainable requires demonstrated pedagogic leadership from the school principal.

14. The leadership attributes associated with initiating and leading sustainable school change and those anticipated to be required in generating school renewal, require differentiation, particularly in terms of the principals’ roles and their understanding of pedagogy and curriculum implementation.

15. Where empowerment is fostered, teamwork and collaboration thrive.

16. Student learning will be enhanced when performance management conversations between the school leader and the teacher collegially address effectiveness, performance and improving students’ learning.

17. A principal engaged in school renewal will need to possess excellent communication and people skills and be prepared to coach and mentor staff.

18. It is better to be a leader among leaders than a leader of followers.

19. Many schools are over-managed by the principal but underled.

20. Delegation is not distributed leadership in schools

21. The school as a learning organisation is an organisation that is skilled at creating, acquiring, and transferring knowledge, and at modifying its teachers’ behaviours to reflect new knowledge and insights.

22. Continuous school improvement and renewal requires a commitment to learning. Therefore, the first step for the school principal is to foster an environment that is conducive to that learning. Noting that not all learning comes from staff reflection and self-analysis. Sometimes, the most powerful insights come from looking outside one’s immediate school environment in order to gain a new perspective on teaching and learning.

23. In the absence of ongoing learning, school staff simply repeat previous practices and therefore, changes remain cosmetic, and student outcome improvements are either fortuitous or at best short-lived.

24. An empowered school is one in which individuals have the knowledge, skill, desire and opportunity to personally succeed in a way that leads to improved student outcome success.

25. Empowerment within a school context is a process of enabling staff to adopt new desired pedagogic behaviours that further their individual aspirations and those of the school in general.

26. When school leaders put the priority on adding value to the schools’ learning and teaching culture, improved student achievement outcomes follow.

27. Value can be added to a school in different ways, such as through changes to pedagogy, the learning environment and relationships with and between stakeholders.

28. Leadership within a school that is predicated on value-adding can best be understood as an amalgam between a value creation mindset and leadership intent with behaviours that are necessary to translate that mindset into quality learning and teaching endeavours.

29. The selection of the right people for school leadership positions is of critical importance as leaders have such a significant impact on overall teacher effectiveness and in turn the overall organisation’s performance and success.

30. Improving emotional intelligence in the school workplace can have a direct and positive impact on:

• The effectiveness of the school's leadership and management

• Staff morale and retention

• Communications and relationship building

• Client satisfaction and student learning outcomes.

31. Effective principals have the skills to manage their own emotions and moods and to influence the emotions and moods of other people towards the best possible outcomes.

32. Public scrutiny of schools and the education enterprise will only increase with time, not decrease.

33. School leaders in renewing schools will need to understand that they have a significant role in growing the intellectual and resilience capacity of all staff, including themselves.

34. An effective school staff concentrates on their core business: the quality of its learning and teaching programs.

35. A principal’s mantra should be that failure is not an option.

36. Schools will increasingly have to risk manage aberrant mental health issues.

37. Growing staff skills, by providing appropriate resources, authority, opportunities, motivation, as well as holding them responsible and accountable for outcomes of their actions, will contribute to general staff competence and satisfaction.

38. Principals are the advocates in every school for optimising every student’s learning capacity, and their catalytic teachers are the enthusiastic leaders who get this done.

39. A principal engaged in school renewal will need to possess excellent communication and people skills and be prepared to coach and mentor both new and existing staff.

40. The levels of accountability required of schools is usually a measure of public trust.

41. Accountability is recognised as a dynamic and heuristic process. It is part of what a school is, not something it does. Each school will need to identify through its planning processes its own path to improvement and then as a collaborative and inclusive exercise, it then becomes a part of everyone’s responsibility.

42. Teachers are more willing to accept the accountability demands required of them if the leader to whom they are accountable has creditability.

43. The commitment to excellent public schooling underwrites our entrenched beliefs in democracy, equity and social mobility.

44. In any school renewal process, the sustainability of a change is often difficult to determine as embedded change becomes the accepted way of doing things over time, and it then becomes the foundational base of the next iteration of renewal.

45. A school renewal process never has just one leader as positional power has little credibility if the renewal is going to be embedded in the practice of every classroom teacher.

46. School leaders need to forecast what values, skills and knowledge their students will need in a society 13 years in the future. And, we all need to be cognisant of what the international testing is telling us about where we sit in what will be the new order.