Most Australian students do not try on PISA Tests

We make students do a lot of tests on top of their regular exams, the fact is that they could well be sick of it and are choosing to focus on the testing that effects them directly above programs like NAPLAN and PISA.

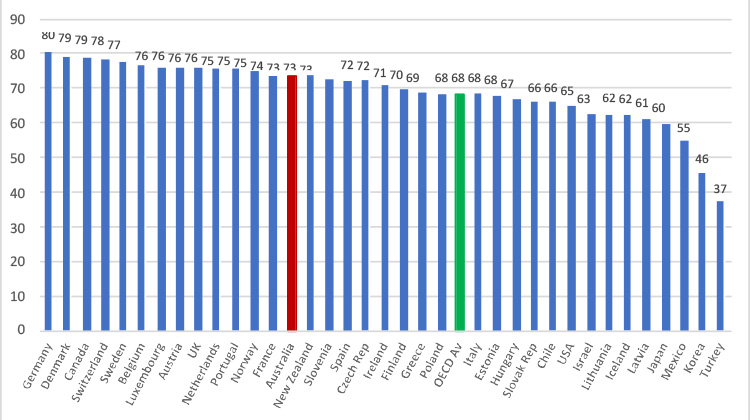

The OECD’s own report on PISA 2018 shows that about three in four Australian students and two-thirds of students in OECD countries did not try their hardest on the tests. There are also wide differences between countries.

Indicative is the contradiction between Australia’s declining PISA results and its improving Year 12 results. Lack of effort in PISA may partly explain this because performance on PISA has no consequences for students as they don’t even get their individual results. In contrast, Year 12 outcomes affect the life chances of students and even students dissatisfied with school have greater incentive to try harder, Australia’s Year 12 results have improved significantly since the early 2000s raises further questions about the reliability of the PISA results.

The OECD report on PISA 2018 shows that 68% of students across the OECD did not fully try [Chart 1]. In Australia, 73% of students did not make full effort. This was the 14th highest proportion out of 36 OECD countries. The report also shows large variation in student effort across countries. Around 80% of students in Germany, Denmark and Canada did not fully try compared to 60% in Japan and 46% in Korea.

The relatively high proportion of Australian students not fully trying may be contributing to its lower results amongst high achieving OECD countries. Five of the six OECD countries with significantly higher reading results than Australia and six out of seven with higher science results had a lower proportion of students not fully trying. These countries included Estonia, Finland, Korea and Poland. However, many countries with significantly higher mathematics results than Australia also had a larger proportion of students not fully trying, including Germany, Denmark, Canada and Switzerland.

The report adds to extensive research evidence on student effort in standardised tests. Many overseas studies over the past 20 years have found that students make less effort in tests that have no or few consequences for them. For example, a study published last year by the US National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) based on data from PISA 2015 found that a relatively high proportion of students in Australia and other countries did not take the test seriously.

There is also anecdotal evidence to indicate that low student effort is a factor in Australia’s PISA results. For example, one 15-year-old who participated in PISA 2015 said:

My peers who took part in this test were unanimous in that they did not, to the best of their ability, attempt the exam.

Less effort in tests leads to lower results. As the OECD report on PISA 2018 states: “differences in countries’ and economies’ mean scores in PISA may reflect differences not only in what students know and can do, but also in their motivation to do their best”.

There is little direct evidence of declining student effort in PISA as a factor behind the large decline in Australia’s PISA results since 2000. However, there is evidence of increasing student dissatisfaction at school which might show up in reduced effort and lower results.

Student dissatisfaction at school amongst 15-year-olds in Australia has increased significantly since 2003. The proportion of students who feel unconnected at school increased by 24 percentage points from 8 to 32% between PISA 2003 and 2018. This was the 3rd largest increase in the OECD behind France and the Slovak Republic [Chart 2]. In PISA 2018, Australia had the equal 4th largest proportion of students who feel unconnected with school in the OECD.