Moving from good to great

Going from good to great isn’t necessarily easy. When something is going well, often there is no impetus to do it even better. “Why bother, the results speak for themselves? Our students perform well above norms.” In these circumstances, it can take a conscious effort to entertain possibility, shift practice and do things differently. Despite this, Mater Dei Primary School in Toowoomba, Queensland, made the deliberate decision to move from good to great.

A co-educational Catholic primary school, Mater Dei’s 420 students typically come from families with high educational expectations and community involvement. In 2017, the school committed to a three- year “visible learning lighthouse project.” Informed by John Hattie’s seminal meta-analysis of what works best in education (Hattie, 2009), the project formed the basis of a re-evaluation of practice. Enabled and supported by the Toowoomba Catholic Schools Office (TCSO) and facilitated through Corwin Australia, the three-year project has now embedded practices that illuminate possibilities for all.

How it happened

Essentially, we:

• prioritised strategically for time, people and money

• facilitated staff selection of impact coaches

• established broader teams of key influencers

• established localised baseline data on effective teaching and learning via

• student voice

• teacher perception

• collective teacher analysis of lessons and classroom practices

• identified student and staff behavioural dispositions essential to productive learning

• integrated the dispositions into

• school behaviour support processes

• staff individualised reflection and goal setting

• refined teacher practices through

• consistent integration of high yield strategies

• development of “Hub” spaces for collaborative data analysis and formative teacher planning

• developed an llluminating Possibilities Learning Framework which reflects the interrelationship between teachers, students and the curriculum premised on

• Learning dispositions

• Learning process

• Action/impact cycles

• School culture.

• celebrated our collective efficacy.

Strategic prioritising

Committing to the three-year project involved strategic allocation of time, money and people. Visible learning priorities were written into our Annual Action Plans to ensure the maintenance of a strong, singular focus. This entailed the allocation of pupil free days to whole staff professional development, further release days for leadership and school impact coaches and budget considerations to enable this. Operationally, the restructuring of timetables and duty rosters allowed for an increase in collaborative time available for cohort level professional learning teams to meet.

Impact coaches and key influencers

One key element in the success of the project at Mater Dei was the fact that change was driven by the teachers themselves. From the beginning, the leadership team recognised that a top-down approach would not be as effective as teacher-led initiatives. Staff nominated two classroom teachers to be School Impact Coaches. Well regarded by their colleagues, these teachers had cultivated positive and productive relationships with their peers and the leadership team.

These key teachers rapidly established a broader team of teachers, and it was this team that became influencers and early adopters in change of practice. This “Visible Learning Team” met regularly in their own time to discuss and share the successes and failures they experienced. As change started to become evident in pockets across the school, diffusion of ideas occurred. Nurtured by our team of early adopters, a critical mass was reached and within twelve months saturation levels were evident (Rogers, 2003).

Establishing a baseline

The first step in any journey is identifying where you’re starting from. Baseline data were collected in early 2018 regarding perceptions of what learning is, what makes an effective learner and an effective teacher, and feedback. Our baseline data provided us with the following information:

• Students voiced that learning and being a good learner was based on behaviour. They stated that listening to the teacher and trying hard makes a good learner. Twenty-four percent could not describe the characteristics of a good learner.

• Teachers felt learning was presently teacher directed. Their understanding of their impact on student progress was highly variable, 50% indicated they used student data to inform practice and 50% were unsure how they measured their impact.

• Students saw teachers as keepers of knowledge, with 42% indicating they did not know what they were learning about and 24% indicating they learnt whatever the teacher told them to. They described effective teachers as helpful and nice.

• Students had a shallow understanding of feedback, with 25% not knowing what feedback was and 34% not knowing how to give feedback.

• Teachers felt they had little opportunity to give or receive feedback from their peers however they felt it often improved their practice.

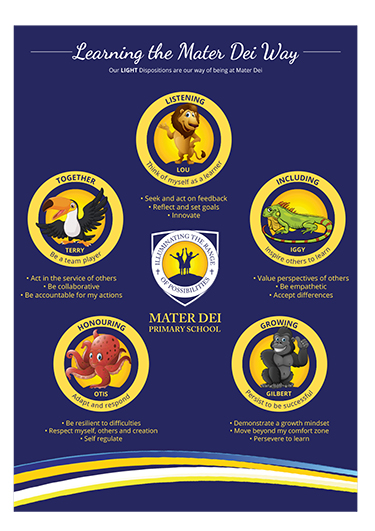

Developing our Dispositions

The first area we decided to address was gaining a consistent understanding and common language around learning. This came as a consequence of visiting other schools in both Australia and New Zealand. We noticed commonalities in schools where learners were able to talk with confidence about their learning. Digging deeper into what made some schools more successful than others, we found that a shared understanding and language about learning was key.

Revisiting our “why” was, and continues to be, a key element of our journey. Thinking from the inside out or knowing and following your purpose or belief is at the core of inspiring others (Sinek, 2009). Our “why” is our school vision, Illuminating Possibilities. Our professional learning with Corwin facilitated an analysis of the dispositions we, as staff, saw as integral to achieving this vision, examining the qualities of an effective learner and the traits we wanted in our learners. We also extended this opportunity to parents and gathered a significant proportion of responses from them.

The dispositions of effective learners that our community identified as paramount were housed under our values. They are deeply contextualised to our school, integrating a Catholic perspective and acknowledging our cultural background. Significantly, a firm belief has been cultivated that our dispositions apply not only to students but to staff too. Just as students are expected to reflect and set goals, move beyond their comfort zone and value the perspectives of others, so too are staff.

Identifying our dispositions gave us the starting point for a common language. Using this language in our classrooms, class awards and communications with parents soon built common understanding and an easy means to foster the development of these learner characteristics.

Refining practice

Running concurrently with the implementation of our dispositions was an evolving understanding of the need for clarity; both for teachers to know exactly what their intended learning objectives were, and for students to know what constituted success. Developing quality Learning Intentions and Success Criteria (LISC) has been an ongoing journey. Initially, teachers felt they had achieved this goal quite easily. However, as we have progressed down this path, we have developed a much more sophisticated understanding of the power of quality LISC.

This evolved into the development of our school Learning Process. Reflecting surface, deep and transfer learning, we attached year level specific cognitive verbs drawn from the curriculum to our phases of “build it, deepen it and transfer it.” This has again provided a common language of learning. Students now collaboratively develop Success Criteria using verbs from each phase of our Learning Process and can articulate in which phase of learning they are.

Another major change has been the visibility and transparency which has been deliberately established across all aspects of our school. We initially developed “The Hub” in a spare classroom. The school impact coaches worked with the leadership team to transform the room into a space where data and teacher planning were visible. While it was a great start and set the scene for a change in mindset about being more open, its geographical location meant it was not utilised as extensively as we envisioned.

To overcome this, again reflecting the prioritisation of our focus, some renovation work was done in our office and staff room, knocking down walls and opening a large central space. The new hub has become pivotal to all that we stand for. In it, thinking is made visible, walls are adorned with notes from collective teacher voice, whole school and year level progress and achievement data, as well as evidence of formative teacher planning. Prominently displayed in The Hub are photos of each staff member displaying something they have learnt over the holidays. Staff share their learning with peers, reflecting on how they learn. This affirms the belief that we are all learners, continually moving through the learning process.

To further refine practice, we have embedded impact cycles. Based on a very simple model of identifying where we are, where we aspire to be and how we are going to get there, our Taking Action Cycle (TAC) is used in response to short, medium and long cycle data. Based on its simplistic success, our TAC is now used by staff at strategic planning levels, for operational considerations, student review and respond meetings and personal goal setting. It is used with students to identify next steps in learning, address behavioural concerns and whole class or cohort goal setting.

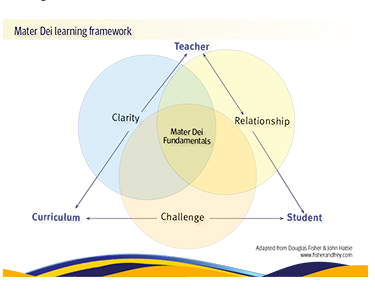

Learning Framework

Over time we have developed an Illuminating Possibilities Learning Framework. Based on the work of Douglas Fisher, our Learning Framework reflects the interrelationship between teachers, students and the curriculum (Fisher at al., 2017). It categorises these dimensions as Relationship, Clarity and Challenge. Where these three dimensions overlap is where we aim our teaching and learning. This sweet spot is where our fundamentals lie. When a positive and productive relationship exists between student and teacher, when both teacher and student have clarity over what is being learnt and when an appropriate level of challenge is provided for each individual, optimal learning occurs.

Our Learning Dispositions, our Learning Process, Taking Action Cycles and school culture form the four key elements of these fundamentals. Representing both technical and human domains, we have invested in these elements as essential to effective teaching and learning.

Collective efficacy

Through an unrelenting focus on these key areas we have, as a school community, changed the way of being at Mater Dei. The belief that through a clear vision and true collaboration we can achieve success has resulted in a sense of collective efficacy (Donohoo et al., 2018), which is palpable across the school. Change is evident in the responses students now give when asked what constitutes an effective learner, with responses typically including descriptions such as learners who seek feedback, set goals, know where they’re at with their learning and can identify their next steps in learning.

Where to next?

As a school community dedicated to moving from good to great, we are not content to remain where we are in this journey. While we recognise we have come such a long way in the last three years, as with any effective learner we continue to set goals and articulate our next steps. With changes coming in the Australian Curriculum, we will be renewing the cognitive verbs each year level uses in their LISC and ensuring teacher clarity with changes. We are also further developing our Taking Action Cycle template to include greater rigour, and using it in new contexts, such as with our school board. Finally, as with anything, the rate of change is not uniform. It’s important that we ensure our whole school community is walking this journey together and that no individual or group is being left behind. Building our accountability to ourselves and each other in this way will continue to ensure our school genuinely illuminates possibilities for all.

References

Donohoo, J., Hattie, J., & Eells, R. (2018). The Power of Collective Efficacy. Educational Leadership, 75(6), 40-44.

Fisher, D., Frey, N., Quaglia, R., Smith, D., & Lande, L. (2017). Engagement by Design: Creating Learning Environments Where Students Thrive. Corwin.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses related to achievement. Routledge.

Rogers, E. (2003). Diffusion of Innovations (5th ed.). Free Press.

Sinek, S. (2009). Start with why: how great leaders inspire everyone to take action. Portfolio.

Angela Martlew is the Assistant Principal at Mater Dei Primary School, Toowoomba, Queensland.

She holds a Master of Education in Online and Distributed Learning and is an AITSL Certified Lead Teacher. Throughout her time as Assistant Principal, and in her previous role as classroom teacher and School Impact Coach, Angela has been a key driver in the implementation of whole school change.

Originally published in AEL Vol 43 Issue 3 2021