School leadership professional learning and skill acquisition: dispelling the myths

School leaders are not born. They are made over time, via processes of professional learning and development which lead to knowledge generation and skill acquisition. The field of principal professional learning and development, however, is heavily impregnated with long-held myths that are proprietorially guarded by training organisations. The concept of a singular, linear route to the knowledge, skills and possible beliefs of school leadership is clearly fallacious and misaligned to the complexity of school leaders' roles. In this paper, the authors will develop the thesis that school leaders in the field will merely survive, rather than thrive, unless they are provided with contextual professional learning and support for meaningful skill acquisition that is situationally relevant to the teaching and learning community in which they lead. Leadership and management have long been partners in a volatile relationship that only adds to the complexity of being a school principal. The lines of this relationship are sometimes so blurred that it is next to impossible to discern the role that management, or leadership, actually plays within the battle arena of school change and school improvements. Muddying this battlefield further, is the concept of context which, when added to the mix, can create misunderstanding; frequently leading to ambiguity and the inappropriate adoption of leadership practices that may not fit the contextual requirements of the school community at that time.

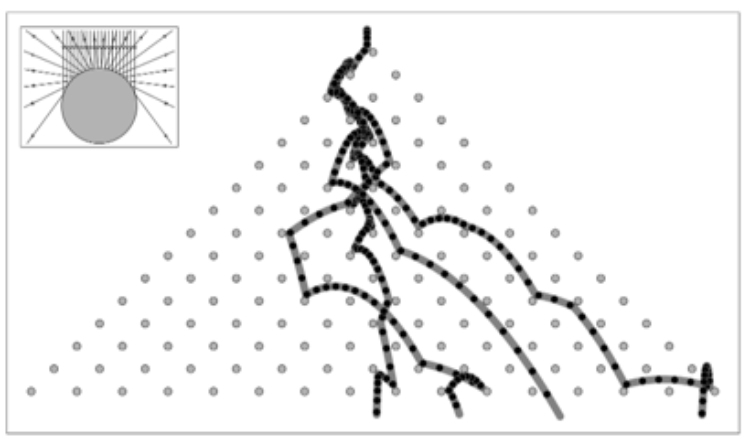

The context of school communities is often a guiding principle for the selection of school leaders. The reality of all schools, however, is that context is never static. What may be required of a principal today, may be markedly different to what is needed tomorrow, relative to their skillset. The interrelatedness of leadership, management and context is not linear, with each aspect reacting with the others like balls in Galton boards (Figure 1). However, while the balls in Galton boards may appear to fall randomly and without any level of predictability. If one were able to examine in minute detail the fall of the ball, the spin on the ball, the speed of the ball and the surface of the peg, the ability to predict the outcome increases. Obviously, the complexity of doing this would make it extremely difficult, however, it delivers the point relative to leadership. These small nuances, mixed with the randomness of human nature, make leadership development rather more complex than adhering to one particular style for any school community.

Figure 1

Professional learning myths

The world of professional learning and development, in the context of school leadership, is driven by compliance directives, leadership standards frameworks and banking knowledge and skills against some unknown problem that school leaders could face. This gives rise to what can be viewed as myths or incorrect assumptions.

Myth 1. The best leadership preparation occurs when school principals learn naturally through their solitary progression from teacher leader to deputy principal, and on to principal; followed by a progression in leading small to larger schools

This erroneous belief is based on the perception that the role of teacher leader, deputy or associate principal will, in fact, be preparation enough for the role of principal. Whilst these roles may open a small window into the intricate challenges of school leadership, the role of principal holds increased complexity, markedly higher levels of responsibility and the requirement for a systems thinking viewpoint that may not be necessary in these middle leadership roles. Additionally, leadership in small schools is, generally, less complex than that of larger schools. Leading in a small school with one or two teachers does not automatically prepare a principal to lead in a larger school supported by deputy principals, teacher leaders and staff in a variety of supporting roles. Similarly, leading in a larger school does not necessarily prepare an individual to lead in a smaller school, often in a rural or remote location, which brings unique challenges related to place, isolation and access to resources. Furthermore, our paper on survivorship bias reminds educational leaders that principals who do not thrive in these early ordeals in school leadership, are not represented when the successful leaders become the high-level directors who define what good principals should learn, and so many of the lessons that could be gleaned from those who barely survive are lost.

Myth 2. It is possible to bank knowledge, skills and values through book and online learning

Paulo Freire (Pedagogy of the Oppressed) developed the educational banking metaphor in relation to students' learning, however this metaphor applies equally well to the learning and development of school leaders. In this metaphor, we see two levels of "learning" in schools; the first level is an “awareness”, while the second is a “doing” or action level. A case in point is school evacuation policies. When administration staff disseminate the school evacuation policy and staff attach it to the wall near the door, the first level of “awareness” (banking) occurs. However, the regular practices of reviewing these policies and conducting drills, which see classes moving to the evacuation points and following the outlined processes, takes this learning to the second embedded “doing” level.

The same principles apply to school leadership development. Undertaking a professional learning course for aspirant leaders which delves into the multiple nuances of school leadership, or reading texts on being a principal and effective leadership, exemplify the first level of “awareness”. It is only when you throw your hat into the ring and take on the role of principal, when you are required to make a plethora of decisions at a moment’s notice for the benefit of your school community, that this learning is taken to the “doing” or action level. In many cases, because the situational context of leadership is overlooked, there will be instances where awareness never moves to an action level, resulting in significant procedural skill decay (PSD).

The concept of PSD acknowledges the old adage that, ‘if you don’t use it, you lose it’. This infiltrates every aspect of the knowledge and skill sets that school leaders and teachers both acquire and need, and it becomes a significant issue in the case of critical incidents in school settings. Without the opportunity to apply knowledge and skills in context, decay occurs. The acknowledgement of levels of skills acquisition in roles such as medical emergencies, are helpful when we consider the skills and knowledge that school leaders require. For example, PSD can be observed in schools when teachers are required to renew their First Aid life-saving skills regularly in refresher courses. While the teacher may be adept at the time of certification, without the opportunity to apply the skill, there is a general degradation of this knowledge.

The banking model of knowledge acquisition is useful only in the sense that it may help a school leader identify the type of problem they face and where to seek help. The critical part of any successful response to school-based problem solving however, is support and/or Just-in-Time-Teaching (JiTT) skill-or knowledge acquisition. In the 1960s and 70s, Toyota developed the concept of Just in Time Production, which became known as the Toyota Production System. It was designed to use resources more efficiently and prevent large warehousing wastage. This concept was then applied in other fields, and JiTT became a useful technique in the field of training. In Australian schools, we have seen examples of JiTT when school communities were required to rapidly establish COVID safety measures and employ vastly different teaching pedagogies than the norm, through developing virtual classrooms to support remote student learning.

Myth 3. An experienced mentor is all that novice principals actually require to thrive as a school leader

This myth helps to perpetuate the survivorship bias that drives myth 1. While mentorship may well be an important element of principal development, a network approach provides a wider lens through which to support development, in that it enables developing principals to consider multiple views and a wider perspective of leadership approaches that may be more contextually relevant to the situation that they are experiencing. A point supported by Bush, Bell and Middlewood (2019) who warned that mentoring is likely to fail when mentors are not carefully selected and purposely matched with the mentees. Furthermore, individuals place different meanings on events dependent on the context in which they occur. Therefore, conveying this context to a mentor, without them having a sound understanding of the context in which leadership is enacted, becomes problematic to say the least.

Myth 4. District meetings and conferences are essential for aspirant leaders' professional learning

The reality is that many of these learning opportunities only ever cover the "I do" component of the "I do, we do, you do" aspects of effective teaching and learning programs. If information is only delivered via the narration of a successful or effective school or system leader, without the opportunity to engage in meaningful discussion and interactions that allow the aspirant leader to contextualise this learning, much of the information is lost at the very moment they leave the building. In situations such as these the learning remains, almost exclusively, in the hands of those providing the learning. Thus ignoring the expertise that the aspirant brings to the program and the contributions that they can provide to the learning.

Additionally, the vast majority of district meetings are abridged versions of staff meetings, where information and directives are provided to school leaders, which they, in turn, must attempt to contextualise within their operational setting to ensure that the learning is meaningful, relevant and in the best interests of their school community. Aspirant school leaders would likely benefit significantly more from the opportunities to step up within their school context to lead in areas of passion and strength; to build their leadership skills and attributes through doing and leading others; through trying and even failing, but trying again; and, ultimately, having their leadership qualities both acknowledged and supported.

Myth 5. Leadership is linear and context is static

This belief drives the creation of models that are often simplistic in nature, in an attempt to explain leadership in a manner that is easily understood. Leadership, however, is complex. Any simplified models overlook, or simply ignore, the interrelationship between the various leadership components in order for effective school leadership to occur. Furthermore, the contexts in which leadership is exercised are never static; they are fluid. Thus, school leadership needs to be elastic to enable it to be exercised in such a way that it can also evolve within this contextual elasticity of school environments. Thereby, helping the principal make sense of the less predictable nature of change and to act accordingly. Recent events as a result of the global pandemic, have highlighted that the leaders who will thrive, and not just survive, are those that are most effective at acknowledging the change agents and adapting or pivoting to best meet the needs of their school community, in their unique context. These principals realise that change is inevitable and responding proactively and positively to these changes - always with the interests of students at the forefront of their decision-making processes - is what encompasses effective school leadership.

Conclusions

The situation of school leaders’ professional development is at best piecemeal and haphazard, while at its worst an exercise in compliance. Without acknowledging that a linear approach to principal professional learning is not well-suited to the fluid and, at times, organic nature of school leadership, or recognising the importance of contextuality to school leadership, there is the likelihood that principals are left floundering without the specific support required to lead and manage their school’s context effectively. Furthermore, by contextualising leadership development, there is a greater likelihood that we can avoid PSD. By adopting the lessons from industry and business that are designed to define a knowledge and skill base in order to maintain safety and operational standards, school leaders and aspirant leaders will be better placed to lead and manage in a way that is contextually relevant to the school community's unique setting.

References

Bush, T., Bell, L., & Middlewood, D. (2019). Principles of educational leadership and management. London: SAGE Publications Ltd

MacNeill, N., & Boyd, R. (2020, September). Redressing survivorship bias: Giving voice to the voiceless. Education Today. https://www.educationtoday.com.au/news-detail/Redressing-Survivorship-Bias-5049

Photo by cottonbro from Pexels