Student Resilience: The Role of Educators, Schools, Families and Communities

The term resilience shifts our focus from psychopathology, disorder and trauma to the many promotive and protective factors that influence child academic and developmental outcomes when a child experiences unusual amounts of stress. With the popularization of the concept, however, has also come many problems. Most notably, in educational settings, there has been an unfair emphasis on a student’s individual responsibility to change and a lack of attention to the many social and institutional factors that make a student’s resilience possible. Paradoxically, the more we focus on how an individual student’s coping is a result of personal strengths (like a positive future orientation, intelligence, self-regulation and grit), the less we see the contributions that can be made to all children’s resilience by the multiple, co-occurring systems that influence successful coping. These other important and resilience-enabling factors include a student’s teachers, the quality of the school environment, family interactions (with all of their caregivers and extended family), and strengths of the broader community. In this paper, I will explore advances to how resilience is understood and several of the most common factors that are associated with positive child outcomes under stress. Educators are especially well-positioned to help children experience resilience, providing access to a number of the “systems” that can make it easier for students to cope with adversity when it happens.

Resilience and Systems Thinking

During a recent consultation with a large school board in Western Canada, I was told the story of a 10-year-old boy who had attended the same elementary school for five years. His behaviour had always been challenging, with a educational assistant assigned to shadow him every day that he attended school. Over time the teaching and support staff had become very adept at managing the boy’s explosive behaviour, often triggered by a sense of frustration with his schoolwork or an insult from a classmate. Even the boy’s peers had adapted to the boy’s unusually volatile behaviour, continuing to play with him on the playground and interact in class when he was calm. There was in every sense a sufficient holding environment to maintain the boy at school. This was in contrast to the boy’s homelife where his mother struggled with a severe addiction and the boy’s father had been incarcerated since his birth. The situation had been stable until just prior to my involvement in the case. Two months earlier the boy’s mother had overdosed and died, a situation which had been anticipated by the social workers involved with the family. Oddly, the boy’s behaviour actually improved after his mother’s death. It was as if the anxiety over not knowing if she would survive the day had been replaced with a degree of certainty that came with the situation resolved. The boy, however, was placed in a foster home. The example was put forward as an illustration of how a school can sustain a young person’s resilience to a potentially traumatizing event.

What was most impactful, however, about the boy’s circumstances was that the foster placement was not within the school district’s catchment area but halfway across the city. Rather than maintaining continuity of attachment with the boy’s only consistent caregivers at the school and doing what we know improves a child resilience, child welfare services had placed the boy in a home that required him to attend a different school. The leadership from the school that he attended prior to his mother’s death intervened, soliciting from its parent committee funds that had been raised to support social and sporting activities at the school. They were, with everyone’s approval, redirected to pay for taxis for the boy to travel to and from the school each day. In other words, it was the school itself which fashioned around the boy a stable environment of positive expectations, peer and adult relationships, daily routines and academic and social supports that were especially important during this period of incredible disruption in the boy’s life. Sadly, institutional players with child welfare had only provided housing but misunderstood their role to make available the many other systems required to support resilience.

Learning from the example, it becomes clear that the “ordinary magic” (Masten, 2014) that is often associated with resilience requires engagement in processes that provide the right combination of individual, social and environmental resources to stimulate positive development. It follows then that the resilience of an individual is intricately linked to the resilience of the social and institutional systems that may appear far removed from the individual’s everyday life but still influence proximal factors like where a child lives, household stress, and a child’s sense of future orientation, attachment and self-worth. Accounting for these interacting systems when modelling patterns of resilience makes it easier to predict which factors within which systems are most likely to improve the functioning of which children exposed to which risk factors. This more dynamic formulation of resilience contrasts with the popularization of the term which is too often used in ways that are divorced from context. For example, we may celebrate when a child from a resettled refugee family reaches university and describe them as having shown grit, or demonstrated a pattern of academic achievement or help-seeking which has made them resilient (in this case, resilience is incorrectly described as a state that is achievable with the right amount of effort). This notion of resilience, however, overlooks the long list of factors which made this success possible, including family values towards education, the quality of schools in the child’s community, language classes, public policies that help migrants to integrate, and accessible and affordable postsecondary education.

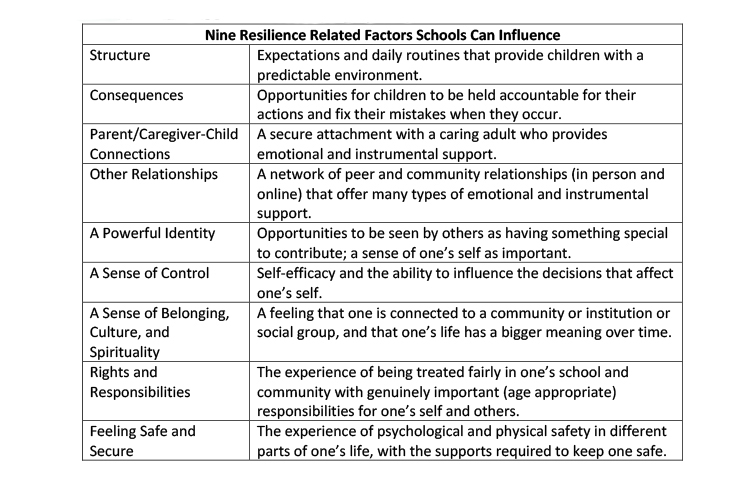

In each case, there are recurring patterns to the promotive and protective factors that are likely to nurture student resilience (Table 1). Schools, as key institutions in children’s lives, are particularly important to making these experiences possible.

Table 1: Resilience related factors (Ungar, 2020)

Mutually Dependent Resilience-Enablers

While each of these nine factors helps a child experience resilience, each depends on other systems for its success. For example, we know that the resilience of educators themselves is associated with the academic performance of the children they teach (Jennings & Greenberg, 2009). Teachers who are provided the necessary training, the supplies, job security and social standing that communicates their value to them and others, are more likely to be effective as educators. Put simply, the more teachers are supported, the more likely they are to create an academic environment that can help children overcome adversity. A teacher’s resilience produces a positive cascade effect which gives children access to everything they need to succeed. At a time when educators are being confronted by an increasingly challenging workload, and spiking rates of anxiety disorders and depression among the children in their classrooms, a multisystemic understanding of resilience opens far more possibilities for helping children heal and grow if attention is focused solely on insisting children take responsibility to change themselves. Interventions that promote mindfulness, for example, have been shown to be mildly effective, but they come with a bias towards individual responsibility for change. The child who doesn’t keep practicing the techniques is somehow to blame for not thriving, when clearly children need far more than meditation techniques to experience resilience when their lives are full of adversity (Ungar, 2019). This is especially important as most of these programs show only short-term effects, with the impact of the instruction decreasing once the intensity of the training ends (Carsley, Khoury, & Heath, 2018).

By considering the impact of multiple systems on children’s academic and social success, however, more opportunities are available to create positive child adaptation. To illustrate, the issue of bullying was initially understood as a problem that could be confronted by a bullied child ‘standing up for themselves’ or finding one other child to align with to make them less vulnerable to a bully’s attacks. That thinking has been challenged in many ways, with the resilience of the bullied child now understood to be a shared responsibility with the capacity of the school system to create a safe school climate with a set of values that promote equitable treatment of all students (Cross et al., 2018). The locus of change has shifted from putting the responsibility for safety on a child themselves to the need for social and institutional enablers that can prevent bullying from occurring and provide a safe space to confront it if it does.

Feedback Loops and Tradeoffs

With a more systemic understanding of resilience as a process that leads to positive outcomes (resilience is seldom expressed as an outcome, but simply the experiences that produce better than expected outcomes in contexts of risk exposure) also comes the need to account for the way systems interact. While there are many possible descriptions of complex patterns associated with positive development, resilience-enabling factors tend to show feedback loops and tradeoffs (Ungar, 2024). With feedback loops, enhancing the resilience of one system (like teacher wellbeing) is expected to have a cascade of positive effects on other systems nearby (student wellbeing improves). Virtuous loops produce positive change, destructive loops spiral a system into lower and lower levels of resilience, making a child unable to cope with the next stressor. In educational settings, one can see the potential benefits to an entire student body when the resources they need to thrive are made available to all students, enhancing the potential of the entire school community to succeed (Quin, Heerde, & Toumbourou, 2018).

There are also tradeoffs to these interactions. Paradoxically, systems that become too resilient can become problems for other systems. When a teacher requires additional support and other staff assist with their teaching load, the net contribution to the climate of the staff team and school functioning is likely to be positive (Theron & Engelbrecht, 2012). But what happens when a number of teachers request leave at the same time, or are not willing or able to do their work? In such a case, a high sense of social cohesion may make it impossible for confrontation. Likewise, empowering parents to be advocates for their children is a demonstrable component for a more resilient child, unless parents protect their children from the consequences to their actions or won’t hold their children accountable when they have been abusive towards a teacher or other students. In other words, the power of any single system needs to be balanced by the needs of other co-occurring systems. A system that is too resilient and does not know when to change or stop a problematic behaviour is one that risks maintaining the status quo rather than transforming into something even better (Ungar, 2024).

How Can Schools Nurture Resilience?

Schools have been found to influence children’s resilience in many ways, though the emphasis on programming designed to change individual children is unlikely to produce sustainable results. Instead, the emerging science of resilience is promoting an understanding of resilience as a combination of both rugged qualities and access to resources (an open access educational curriculum based on these ideas can be found at https://r2.resilienceresearch.org/standard-programs/). When this dual focus is the basis for interventions, schools are more likely to produce the resilience-enabling processes that characterize the lives of children who are successful even when exposed to chronic or acute adversity. Schools that succeed, however, tend to be those that consider the resources required to help children and make those available at different systemic levels, from culturally appropriate curriculum to the quality of the educators, the design of classrooms, access to green spaces, engagement between children, communication with parents and caregivers, and open boundaries with the wider community, including individuals like Indigenous elders, local business owners, service clubs, and of course, government policy makers. The more children are embedded in systems that work well together the more likely they are to experience the school environment as a place they can find the supports they need for optimal development and academic success.

Michael Ungar, Ph.D., is a Professor of Social Work at Dalhousie University where he holds the Canada Research Chair in Child, Family and Community Resilience. He is the author of more than 250 scholarly papers and 18 books for educators, mental health professionals, researchers and lay audiences focused on the diversity of human resilience across cultures and contexts (www.resilienceresearch.org; www.michaelungar.com).

References

Carsley, D., Khoury, B., & Heath, N. L. (2018). Effectiveness of Mindfulness Interventions for Mental Health in Schools: A Comprehensive Meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 9(3), 693–707. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0839-2

Cross, D., Shaw, T., Epstein, M., Pearce, N., Barnes, A., Burns, S., Waters, S., Lester, L., & Runions, K. (2018). Impact of the Friendly Schools whole‐school intervention on transition to secondary school and adolescent bullying behaviour. European Journal of Education Research, Development and Policy, 53(4), 495-513. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12307

Jennings, P. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 491-525. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308325693

Masten, A. S. (2014). Ordinary magic. Resilience in development. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Quin, D., Heerde, J. A., & Toumbourou, J. W. (2018). Teacher support within an ecological model of adolescent development: Predictors of school engagement. Journal of School Psychology, 69, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2018.04.003

Theron, L. & Engelbrecht (2012). Caring teachers: Teacher-youth transactions to promote resilience. In M. Ungar (Ed.), The social ecology of resilience: A handbook of theory and practice (pp. 265-280). New York: Springer.

Ungar, M. (2019). Change Your World: The Science of Resilience and the True Path to Success. Sutherland House: Toronto, ON.

Ungar, M. (2020). Working with children and youth with complex needs: 20 skills to build resilience (2nd Edition). New York: Routledge.

Ungar, M. (2024). The Limits of Reslience: Knowing when to persevere, when to change, and when to quit. Toronto: Sutherland House.

Image by Ramon Crivelli