Teacher Stress, PTSD and Psychological Residue

The concept of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder was first the exclusive domain of military veterans, but over time it was realised that adults and even young children can exhibit the symptoms. Stress, anxiety and PTSD are a part of work in every profession, including teaching. The measures of stress and anxiety are very subjective, and the stress felt by the elite special military operatives is not calibrated the same as that experienced by gentle teaching staff in gentle schools. Basically, stress measures can only be decided by the staff member suffering the stress. Outside observers' opinions are irrelevant about those experienced measures of stress and anxiety because the stress algorithm in a person's head mixes with undeclared, personal traumatic experiences.

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

The Vietnam War was different to other modern wars, and it was one that we did not win in Vietnam, or in Australia. Because of that, public opinion turned inwards on those who had served, and as a result there was an explosion of mental health issues among veterans. In an excellent study of PTSD the French researcher Marc-Antoine Crocq (2000), made comment of the history of PTSD:

‘In the collective mind, this diagnosis (PTSD) is associated with the legacy of the Vietnam War disaster. Earlier conflicts had given birth to terms, such as “soldier's heart”, “shell shock”, and “war neurosis”. The latter diagnosis was equivalent to the névrose de guerre and Kriegsneurose of French and German scientific literature.’

The term PTSD was coined in the 1970s and recognised in the American Psychiatric Association's publication The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1980. These problems for veterans were labelled "disorders" and associated with that pejorative labelling is the concept of victimhood. This was a double whammy for veterans; and teachers and education assistants find themselves in exactly the same position.

In the recent review of PTSD in DSM-5, PTSD was recognised in children as young as one year of age:

‘According to the DSM-5, PTSD can develop at any age after 1 year of age. Clinical re-experiencing can vary according to developmental stage, with young children having frightening dreams not specific to the trauma. Young children are more likely to express symptoms through play, and they may lack fearful reactions at the time of exposure or during re-experiencing phenomena. It is also noted that parents may report a wide range of emotional or behavioral changes, including a focus on imagined interventions in their play. The preschool subtype excludes symptoms such as negative self-beliefs and blame, which are dependent on the ability to verbalize cognitive constructs and complex emotional states’ (NCBI, 2021).

It is interesting that some researchers identify what they call residual trauma, which are the remnants of trauma that persist even after treatment.

Residue

What is interesting is that the treatment for PTSD never removes all aspects of the disorder from the victims' memories. Lebow (2021) noted:

‘Imagine going about your day when you’re suddenly hit with the memory of a past trauma. You drive down the road where your accident happened, and even though you’ve been down this road many times before, those feelings of angst and fear return. But you thought the treatment for your post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) worked, and your symptoms were better. So, why are you having symptoms again? PTSD is a complex condition. Symptoms don’t simply turn “on” and “off” like a light switch. It’s not as simple as that. Recovery is a gradual process. Even after treatment ends, some people with PTSD find themselves having residual symptoms.’

In Australia, Harry Moffitt (ex SASR and author of "Eleven Bats") is a director of the Mission Critical Team Institute (MCTI) (https://missioncti.com/) which has proposed a different way of looking at the dark, regenerating fragments that live in veterans' minds. The MCTI co-founder, Dr Preston Cline, identified what he called "Residue", which is the result of extreme experiences. Dr Cline recognised the problem faced by all veterans: "You are not broken. You are not a victim. You are not a survivor. You have chosen the hard path – a path full of extreme experiences, both good and bad, which leave memories. These memories, in turn, leave a residue within you, which if processed can serve as the fuel that moves us to wisdom and joy. If unprocessed, however, it will begin to build up, to harden, until you can no longer move or breathe, until all you know is pain and sorrow".

He went further to note: "I have come to see “residue” as neither good, nor bad, only the substance that experience and memories leave behind. We often think about the bad days that mark our lived experiences, but we should also consider those extraordinary day when we overcame a previously perceived limitation".

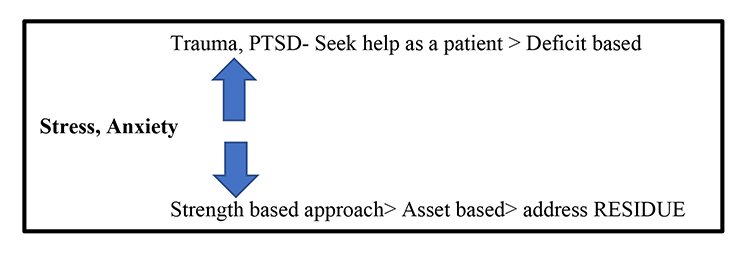

Figure 1 Residue: The Strength Based Alternative Treatment Model

Addressing Residue

In Dr Cline's research he worked with the military's elite operators and others, but the findings are applicable across a broad range of occupations that generate trauma. Dr. Art Finch, who compared WWII veterans with Vietnam veterans regarding rates of PTSD and combat stress, noted the time it took to return home. By the 1970s, Vietnam veterans were landing on U.S. soil hours after being in combat. Whereas, WWII veterans boarded ships that took 2–4 weeks to return home, allowing soldiers the opportunity to share war stories, make meaning of their experiences collectively, while simultaneously preparing for homecoming by talking about what they most missed and hoped to do first (expectancy). The British military used ship transport, and not planes, to bring their veterans home from the Falklands and this time for group absolution lessened the occurrence of PTSD.

In summary, Dr Cline promotes asset-based, positive treatment approaches, as can be seen in Table 1, and it provides a sharp contrast to the commonly used deficit based treatment.

| Asset Based | Deficit Based |

| Strengths Driven | Needs Driven |

| Opportunity focus | Problems focused |

| Internally focused | Externally focused |

| What is present that we can build upon? | What is missing that we must go find? |

| May lead to emergent and novel solutions | Often leads to downward spiral negativity |

Table 1 Asset and Deficit Based Treatment Approaches

Applying Dr Cline's Approach to Teacher and Education Assistant Stress and Anxiety

We were excited by Dr Cline's starting point (He says, "What you are doing is honourable.") and then addressing the issue of residue memories and feelings that haunt sufferers in the middle of the night.

So, our starting position is that doing teaching is an honourable act, and we are fulfilling a high moral purpose. We have to expect some collateral damage as the students whom we have been sheltering suffer some serious grief. It is NOT the teacher's fault! Dr Cline's Asset Based approach argues that through a group absolution type process, the psychological damage to staff can be ameliorated.

Conclusion

The "Residue" approach positively contrasts with the clinical approach used to treat issues such as PTSD in traumatised staff, which often exhibits the residual return of the problem even after treatment. The message that MCTI promotes is that of service, suffering, honour, and the comradeship of shared experiences. If this approach works with individual cases, then it is far better than labelling trauma sufferers with a disorder, and then controlling aspects of their lives.

This new approach is certainly worth exploring, given the current Workers' Compensation rates among teachers and education assistants. And, it is probably not going to get much better.

References

American Psychiatric Association (2020). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5).

Cline, P.B. (2020). Residue. Mission Critical Team Institute. https://app.box.com/s/6zbzt8tlxt82n2kvbweb5ojxbp6jndpk

Crocq, M-A. (2000, March). From shell shock and war neurosis to posttraumatic stress disorder: A history of psychotraumatology. Dialogues Clinical Neuroscience. 2(1), 47–55. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3181586/

Lebow, H.I. (2021, June). Residual Symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. PsychCentral. https://psychcentral.com/lib/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-residual-symptoms#residual-symptoms

National Centre for Biotechnology Information (2021). DSM-5 Changes: Implications for child serious emotional disturbance [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519712/