Teaching with joy and humour: Learning human-ness in the classroom

A Year 3 teacher is wearing a jumpsuit (a one-piece pant suit) to class. A small student compliments her, “Miss, you look so pretty today,” Another cheeky student adds, “But Miss looks like she is wearing her pyjamas to school today.” The teacher quips back, “Well I look pretty stylish for rolling out of bed then, don’t I?” The whole class laughs. There is a warmth and sense of ease that is prevalent in the atmosphere. The morning begins, and the class resumes in order and students get ready to start the day, on a positive and light-hearted note from the earlier laugh.

In teaching, we are told that there is a fine line between joyful humour and chaos in a classroom. Many teachers play safe, and they separate the humour from the "instruction". However, we note that the brilliantly engaging teachers see this as a false dichotomy that need not exist. Expert teachers have an innate ability to teach with a wonderful mix of joy, humour, and purposeful teaching goals. And, as a result students learn essential intellectual and social skills while having the mandatory dose of curriculum learning. Secondly, a massive change in teaching is that teachers are now required to engage and motivate all their students to learn. The algorithmic representation of the modern teaching and learning process can look like: APPROPRIATE HUMOUR > MOTIVATION > ENGAGEMENT = IMPROVED LEARNING, which supports contemporary hypothesizing (Wanzer, Frymier, & Irwin, 2010).

Joy and Engagement in School

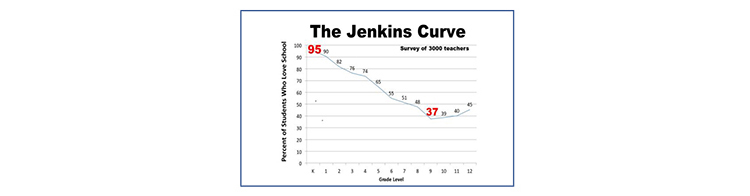

The research by Lee Jenkins (2021) showed what every teacher, and every parent already knows- students find their school experiences become less joyful as they move through the school Year levels. Jenkins's research found that teachers believed that students perceived school as being less joyful as they progressed through schooling.

Figure 1 The Jenkins Curve

This Jenkins Curve is not unexpected. Just imagine that we have a classroom full of young students and our educational goal is to teach them to ride a bike. Yes, we start with trainer wheels and move on to supported bike-riding. When the child experiences bike-riding independence we can see real joy. If we were to continue on a 12-year program leading to riding in the Tour de France, most of our students will lose interest, which is no different to what we are seeing in the Jenkins Curve. The learning content and context becomes more time-hungry and if it doesn't match students' future visions and then the learning becomes a chore, which is not a joyful experience. We see the injection of humour into the teaching act as generating happiness, joy, interest and motivation through enhancing the student- teacher relationship.

Instructional Humor Processing Theory (IHPT)

Interestingly, the topic of appropriate pedagogic humour attracts an increasing degree of interest in educational research, as teachers and school leaders reaffirm that an essential part of the teaching act is motivating their students.

| Typologies of Humour |

||||

| Physical |

Verbal/Intellectual (Martin et al. 2003 |

|||

|

Slapstick |

1. Affiliative humor |

2. Self-enhancing humor |

3. Aggressive humor |

4. Self-defeating humor |

|

Instructional Humor Processing Theory (IHPT) Wanzer, Frymier, and Irwin (2010) |

||||

|

"Working from the propositions of IHPT, we predict that instructors’ use of related humor will be positively associated with learning because this type of humor should enhance both students’ motivation and ability to process information" (p. 7). |

||||

| Inappropriate humour |

Appropriate humour |

|||

| Improved engagement and learning |

||||

Figure 2 Typologies of Humour

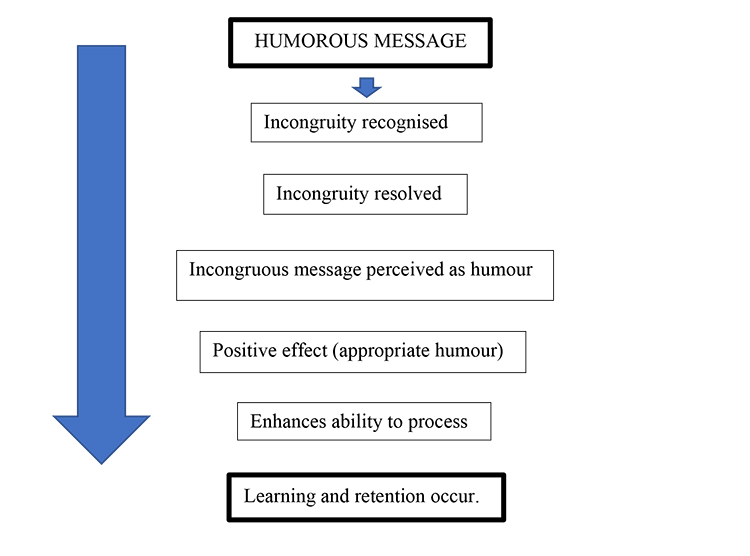

Wanzer, Frymier, and Irwin (2010) have studied interest in instructional humour and the decision tree thought analysis for humour that enhances learning looks like this:

Humour, Theory of Mind (ToM) and Students' Intelligence?

There are many aspects of intelligence that are sadly neglected, and humour is a key indicator of an intelligence that needs further exploration. As teachers we see stumbling Year 3 students trying to recount jokes and riddles, and some students trying to develop their own unfunny variations. Many of us are left wondering what that chicken wanted to cross that road, after being asked by students.

Theory of Mind (ToM) (Airenti, 2015) provides a useful insight of how the ability to understand what others are thinking is closely related to the ability to comprehend humour for children. The ability for children to discern "non-serious" communication is a key to ToM. For example, Airenti (2015) reported children's literal comprehension of the non-serious matters does not happen before the age of 5 or 6, but they start to learn earlier:

‘For instance, if a character said to another character who had just broken a plate: “Your mommy will be happy!” children were expected to understand that the intended meaning was that the mother would be upset. The goal was to have a comprehension task not burdened with ToM difficulties. In this condition we were able to show that even children as young as 3 years of age might understand the non-seriousness of an ironic utterance.’

The Theory of Mind notes the significance of humour in developing cognitive fitness, social skills, and creativity is sometimes lost in some classrooms. Teachers who practice appropriate humour in the classroom are not only enhancing the learning process by creating a warmer, more positive environment which in turn intrinsically motivates students, but they are demonstrating a higher degree of verbal intelligence, which is directly linked to overall intelligence.

Example

Telling news is an occasion in early childhood classrooms where teachers and students can identify what counts as humour.

A young student from India (recently arrived in Australia) is telling the class of how over the weekend, he did not do his homework so his Mum had said to him, “You have been a naughty boy, so I will slap you hard enough that you will go flying all the way back to India.” He finishes with the expectation that the class will relay laughter, as he told the story with the intention of creating a bit of class comedy.

The class was more concerned that he had stated that his Mum may “hit” him for punishment. The news was not meant to be of a serious manner, but there is an uncomfortable silence in the classroom, thereafter. In a western classroom, students are not used to hearing their peers being “slapped” even for fun.

Whether there is East-West cultural difference in humour perception, understanding how culture influences humour perception and humour usage, is of great importance because humour has significant consequences for human psychological well-being (e.g. Martin, 2001; Chen & Martin, 2007).

Conclusion

A lot of history’s brilliant minds were also funny people. Stephen Hawking, the most renowned scientist was known for playing on tricks about his identity on his own computer. Albert Einstein once noted, “Any man who can drive safely while kissing a pretty girl is simply not giving the kiss the attention it deserves.” There may be something more to this than simple coincidence.

Adding human-ness to the perceived role of a teacher may also bridge a gap between the teacher/student relationship. Humour can lead the establishment of teacher/student rapport which is another characteristic of master teachers. Patrick Kelley, the author of “Teaching Smarter” (2015), argued that using in the humour in the classroom has various benefits from reducing stress, to increasing productivity and fewer disciplinary problems. But perhaps most pointedly he stated that using humour creates more “student buy in,” which essentially is a key aspect in the role of a teacher.

Many education programs now tell potential educators that teaching is a performance art, and scholars such as Wanzer, Frymier, and Irwin (2010) contended appropriate instructional humor usage in the classroom not only engages an audience, but is directly connected to student learning and achievement. Studies have linked humour to lower stress levels, increase self-esteem, empathy, and interpersonal attractiveness. Adopting appropriate instructional humour allows for educators to create a uniquely personalised classroom experience. This in turn, encourages student engagement and results in increased information retention. The teachers’ usage of closely related content based humour is positively correlated with student learning. This type of humour should enhance student motivation and information processing in its approach (Wanzer, Frymier & Irwin, 2010).

Expert teachers know that humour plays an important role in interpersonal relationships, as a method of enhancing positive interactions, facilitating self-disclosure and defusing tension and conflict. On the other hand, negative types of humour, such as aggressive teasing and sarcasm, may impact negatively on social relationships (Martin, Puhlik-Doris, Larsen, Gray, & Weir, 2003). Thus, the sensible use of humour particularly by teachers in the classroom may be an important social skill in itself, and may also contribute to enhancing social competencies in students, such as the ability to initiate social interactions, and manage conflict.

Key words: Humor, Humour, Instructional Humor Processing Theory (IHPT), Instructional humour, Pedagogic humour.

References

Airenti, G. (2015, August 14). Theory of Mind: A new perspective on the puzzle of belief ascription. Frontiers in Psychology. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01184/full

Chen, G., and Martin, R. A. (2007, January). A comparison of humor styles, coping humor, and mental health between Chinese and Canadian university students. Humor- International Journal. Humor Research, 20, 215–234. doi: 10.1515/HUMOR.2007.011

Jenkins, L. (2021, November 26). Education's greatest challenge. Education Today. https://www.educationtoday.com.au/news-detail/Education-5477

Kelley, P. (2015). Teaching smarter: An unconventional guide to boosting student success. Free Spirit Publishing.

Martin, R. A. (2001, July). Humor, laughter, and physical health: methodological issues and research findings. Psychology Bulletin. 127, 504–519. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.504

Martin, R., Puhlik-Doris, P., Larsen; G., Gray, J., & Weir, K. (2003, February). Individual differences in uses of humor and their relation to psychological well-being: Development of the Humor Styles Questionnaire". Journal of Research in Personality 37(1), 48–75. doi:10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00534-2.

Wanzer, M. B., Frymier, A. B., & Irwin, J. (2010). An explanation of the relationship between instructor humor and student learning: Instructional humor processing theory. Communication Education, 59(1), 1-18.

Photo by Marko Tuokko from Pexels