The Impact of Social-Class on Australian Education, and the Development of Caste-like Stereotypes

This paper discusses the intricate interplay between social class, social disadvantage, and their influence, spanning both short and long-term effects, on students' educational outcomes and attitudes. The paper delves into how students' encounters with the inequality shape their attitudes, and subsequently impacts their future socioeconomic trajectories. The narrative posits that individuals residing in contexts of relative deprivation are predisposed to educational setbacks, poorer health prospects, and heightened marginalisation in social and economic spheres. Furthermore, within the Australian context, there exists a discernible attitudinal disparity characterised by rationales involving economic reliance on welfare distribution.

In Australia, much like in other parts of the world, the coronation of King Charles III drew attention to the persistence of a caste-like social stratification within British society and its impact on the wider Commonwealth community. Observers noted how certain elitist segments of British society remained distinct from the masses, emphasising the presence of entrenched class and caste divisions. The religious aspects of the coronation, while historically significant and integral to the ceremony, did not necessarily promote inclusiveness. Instead, the ceremony underscored existing social hierarchies that were evident in the audience construction.

In educational discussions, it is often commented upon that student educational outcomes are more reflections of the economic advantages and disadvantages seen in the wider Australian society context. Research evidence would indicate that there indeed exists a high correlation between a student’s learning outcomes and certain socio-economic characteristics such as the parents’ occupation or level of education, the family’s income bracket, and the location of the students’ homes. Students from low socio-economic areas are in fact consistently outscored in national testing by those students from wealthiest suburban homes. These dismembering factors are built into the construction of the Index of Advantage (ICSEA). ACARA (2024) noted:

ICSEA= SEA + Remoteness + Percentage of Indigenous students enrolled.

The SEA is calculated from parents’ occupations, and educational levels.

Over the past 30 years or more the notion of welfare dependency has significantly influenced social policy debates in Australia and the development of caste-like perceptions in the general public. Welfare dependency, as conceptualised, suggests that prolonged reliance on government assistance in terms of welfare payments can erode an individual's character and foster a pervasive culture of dependency. This reliance may permeate communities and, be generational in nature establishing in some instances this culture of dependency where a person’s outlook is characterised by resignation and ongoing pessimism. According to this perspective, individuals reliant on welfare may become oblivious to economic opportunities that are presented to them, preferring to persist on income support even when viable employment opportunities are made available.

While welfare dependency is sometimes narrowly defined to encompass specific forms of income support, it remains intricately linked to broader dependency concepts and can imply certain stances on causation and moral responsibility. For education systems, the challenge of welfare dependence is viewed as more complex than simply offering education, training, or work-place opportunities, or facilitating access to services that mitigate obstacles associated with economic hardship which exacerbate a social - cultural disconnect with schooling, as families struggle to afford requisite school materials.

Often, marginalised students come from families that are caught in a poverty trap and cannot afford some of the more desired curriculum options. The inability of these families to meet the cost of school expectations creates further issues for the students because when they come to school without the necessary equipment it reifies the problem alienation they feel.

Social Stratification

Social class, and caste in a classical sense are often linked, however, caste is a closed system, while class has a degree of flexibility for movement of members. The great Indian mathematician, Ramanujan, was extremely poor, but being Brahmin enabled him to mix with important Brahmin leaders. Kanigel (2014, p. 81) observed that ‘… in India, economic class counted for less than caste’. It is important to examine social class, and caste, because generations of unemployed, poor people (now called the ‘precariat’) are found in Western societies, and this predictive rigidity is extremely difficult for the generationally-poor to break.

Kingsley Davis and Wilbert Moore (1945) enunciated the principles of societal stratification and they noted the universality of stratification:

‘Starting from the proposition that no society is ‘classless,’ or unstratified, an effort is made to explain, in functional terms, the universal necessity which calls forth stratification in any social system’ (p. 242). This functionalist view inadequately addresses power, mobility, and the passage of time because in traditional societies, power and wealth determine societal roles in the world of realpolitik.

Caste

The meanings of caste usually follow the Merriam-Webster definition: ‘… a system of rigid social stratification characterized by hereditary status, endogamy, and social barriers sanctioned by custom, law, or religion.’ Reference is usually made to the concept’s origins in the Hindu religion, with links to India, but the concept is now being used elsewhere where stratification and wealth can be determined through multiple generations, social barriers are constructed, and unofficial endogamy falls into place. Generational poverty has exacerbated aporophobia- fear of poverty (Boyd, Silcox & MacNeill, 2023), and it has generated caste-like perceptions of the poverty afflicted stratum of society. There are many social, welfare and economic consequences for being poor and in schools, staff get insights into these aspects of society and students’ lives, which breaks the hearts of many sensitive teachers.

The American writer, Isabel Wilkerson (2020), noted:

‘A caste system is an artificial construction, a fixed and embedded ranking of human value that sets the presumed supremacy of one group against the presumed inferiority of other groups on the basis of ancestry, and often immutable traits…. A caste system uses rigid, often arbitrary boundaries to keep the ranked groupings apart, distinct from one another, and in their assigned places’ (p. 17).

The overlap with the concept of social class is that caste is determined at birth by a set of rules, and in Western society where we see pre-determined configurations of the rich and poor, it can be argued that in most cases social class, like caste, is determined at birth. Wilkerson observed (2020, p. 70) that racism and casteism are interwoven in America, and she observed:

‘Any action or structure that that seeks to limit, hold back, or put someone in a defined ranking, seeks to keep someone in their place by elevating or denigrating that person on the basis of their perceived category, can be seen as casteism’ (p. 70).

In defining caste, Young and Arrigo (1999, p. 40) said, caste is a:

‘… system of social differentiation and stratification in which one set of persons are defined as inferior or superior in some important respect. Life chances and life courses are determined at birth in societies organized by caste. Capitalism tends to replace caste systems with class systems’.

Following on from this view of the role of capitalism and class, research by the Australian National University (Sheppard and Biddle, 2015) proposed that there are five social classes in Australia:

‘The five observable (or ‘objective’) classes in Australian society can be described as an established affluent class, an emergent affluent class, a mobile middle class, an established middle class, and an established working class. These classes are made up of individuals and there is obviously some variation within each class. However, members of each class share plenty of common traits’ (p. 4).

This research failed to identify the generationally unemployed, who do not make the working-class entry.

Class, Social Mobility and Caste

Class is one lens that has been used to describe the divisions in society, and in the modern era this concept has become more discerning with the BBC (2013) now reporting research that claimed there are seven classes in the United Kingdom society: the elite; established middle class; technical middle class; new affluent workers; traditional working class; emergent service workers; and the precariat, or precarious proletariat. The revelation of this new class called the precariat is important because the associated poverty not only affects the adults, but their children can suffer set-backs, even before they are born. David Kirk (2020) in his study of precarity, listed some of the health and social issues that this group face:

‘In conditions of precarity, a number of additional issues accompany these socio-economic factors to affect young people’s health, such as parental unemployment, exposure to domestic violence, experience of abuse in childhood, level of mothers’ education, childhood bullying, crowded housing, and parental depression’ (p. 34).

These social and health issues impact on individual’s potential to attain social and financial mobility.

The temporal factor is also considered when labelling class, and judging caste. For example, we see discounting references to the “nouveau riche”, and “old money”, and the nomination of “life peers”. However, one wonders how many generations a family has to be unemployed, unemployable, and poor before it is recognised as part of a caste of “untouchables”.

In Australian education we have seen new teacher generations enter a “Field of Dreams”, contaminated with the Pygmalion Effect (Boyd & MacNeill, 2020), with the intention of solving the education-caste conundrum, only to retire 40 years later with no perceptible change to the parlous situation for marginalised families. What teachers are seeing with many marginalised students is that education is not bridging the achievement-gap and providing a key to a significantly different lifestyle, or life trajectory.

Overcoming Educational Marginalisation of Students

To ensure effective education for marginalised and economically challenged students, educators need to shift away from passive teaching methods toward more active, collaborative learning environments. This would require a prioritising of practical relevance and purpose-driven curriculum development, incorporating real-life examples to boost student engagement and the relevance of learning outcomes. Such a conducive learning environment may involve fostering an atmosphere where group discussions and team assignments become the norm.

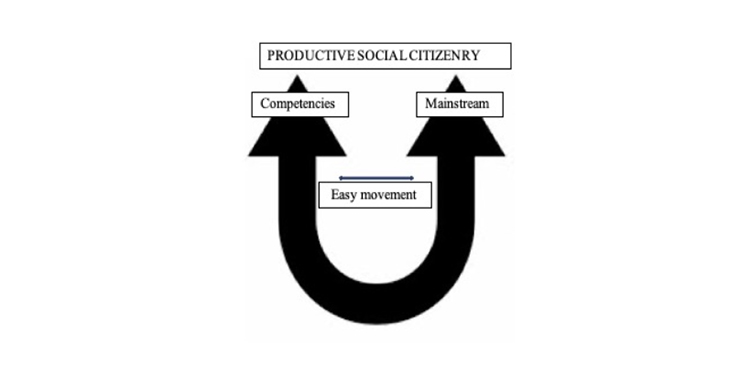

In meeting these diverse student needs, educational programs should blend life skills with academic pathways, integrating TAFE and school education with a focus on competency frameworks. This approach breaks down traditional barriers, enabling smooth transitions between academic and vocational streams while nurturing holistic skill development. Course content should be purpose-driven, offering practical relevance and developed collaboratively with input from stakeholders in the field.

Moreover, it's crucial to establish collaborative partnerships among educators, TAFE institutions, and education departments. These partnerships are vital for designing integrated post-primary programs that address the diverse learning needs of marginalised students.

Looking ahead, educational approaches must evolve to accommodate the specific requirements of marginalised students. Embracing micro-competency models, flexible learning pathways, and integrated TAFE-school programs presents promising opportunities for fostering inclusive education and should be explored further.

Effectively addressing the needs of marginalised students necessitates a concerted focus on cultivating authentic relationships, employing responsive pedagogy, and providing practical, incentivised learning experiences. It is only through collaborative, holistic approaches that we can break down persistent barriers and enable these students to unleash their full potential as engaged participants in their educational journey and beyond.

Discussion

What we see with growth of the generationally welfare dependant groups in society is the development of harmful stereotypes that brand these people as the equivalent of the Indian dalit (downtrodden/ broken) class, or the European Cagots. A part of the solution, and re-establishment of “A Fair Go for Everyone” is a rethink on engaging and supporting these marginalised students in a new, inclusive educational program that teaches life competencies; bans on racist labelling (particularly in the ICSEA equation of (dis)advantage); moves to competency successes not normative rankings; and incentivises competence-based learning.

For most Australian families, watching the nightly television news has become more depressing with the explosion of youth crime. As educators, it is time to think outside the embedded curricular and schooling boxes, and re-engage the students of today and tomorrow.

References

ACARA (2024). A guide to understanding ICSEA (Index of Socio-Educational Advantage)values. ACARA. https://docs.acara.edu.au/resources/Guide_to_understanding_icsea_values.pdf

BBC (2013). Huge survey reveals seven social classes in the UK. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-22007058

Boyd, R., & MacNeill, N. (2020, July 5). How teachers’ self-fulfilling prophecies, known as The Pygmalion Effect, influence students’ success. Education Today. https://www.educationtoday.com.au/news-detail/How-teachers-4986

Boyd, R., Silcox, S., & MacNeill, N. (2023, May 5). Aporophobia: Poverty is not a learning disability (for discussion). Education Today. https://www.educationtoday.com.au/news-detail/Aporophobia-5916

Davis, K., & Moore, W. (1945, April). Some principles of stratification. American Sociological Review, 10( 2), 242-249.

Henry, J. (2023). Tribalism in modern society: Understanding dangers and solutions for a divided world. Amazon.com.au

Kanigel, R. (2014). The man who knew infinity: the life of the genius Ramanujan. Abacus.

Kirk, D. (2020). Precarity, critical pedagogy and physical education. Routledge.

Patil D., Enquobahrie, D.A., Peckham, T., Seixas, N., & Hajat, A. (2020). Retrospective cohort study of the association between maternal employment precarity and infant low birth weight in women in the USA. BMJ Open. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029584

Sheppard, J., & Biddle, N. (2015). ANU Poll 19 Social Class, 2015. Canberra: Australian Data Archive, The Australian National University.

Wilkerson, I. (2020). Caste: The origins of our discontent. Penguin Books.

Young, T.R., & Arrigo (1999). The dictionary of critical social sciences. Routledge.