The Softskills in Leadership are Essential to Develop Effective, Caring School Cultures

Schools are about the aspirations of families, children, parents and communities, and to use a business metaphor, education is a people industry. At this present time, Western schools and education are just now emerging from an era driven by hard-core business values and contractors who valued toughness and efficiency. This the newly emerging generation of school leaders, who were not aware of how this different milieu developed, may rightly query the knowledge, skills and values metrics by which school leaders were judged as the pendulum of change swings back to a more balanced position, and the so-called leadership softskills suddenly become more important.

In schools, the softskills are the aspects of teaching and school leadership that influence the major, continuous aspects of school culture. To a degree the softskills are neglected, or they take second place because they are hard to quantify, and they are not as flashy as a new maths program or language program that increases schools’ national testing rankings. Softskills are more likely to be found in the ‘how’ of teaching, rather than the ‘what’ is being taught.

New Public Management: Schools are Businesses

New Public Management (NPM) developed in the second half of the Twentieth Century because of a disenchantment with the cost of government services. While Thatcherism was blamed for this in the United Kingdom, the sentiments were common around the world and the American version was labelled neo-liberalism. Stephen Osborne and Kate McLaughlin (2002, p. 10) in a chapter titled, ‘The New Public Management in Context’ identified seven characteristics of what NPM meant:

1 A focus on hands-on and entrepreneurial management, as opposed to the traditional bureaucratic focus of the public administrator (Clarke and Newman, 1993);

2 Explicit standards and measures of performance (Osborne et al., 1995);

3 An emphasis on output controls (Boyne, 1999);

4 The importance of the disaggregation and decentralization of public services (Pollitt et al., 1998);

5 A shift to the promotion of competition in the provision of public services (Walsh, 1995);

6 A stress on private sector styles of management and their superiority (Wilcox and Harrow, 1992); and

7 The promotion of discipline and parsimony in resource allocation (Metcalfe and Richards, 1990).

This business model was to be developed within an enterprise context, with a hands-off approach by government.

In schools, NPM resulted in imitations of what could be seen in business, with strategic and business plans entering the jargon, along with financial accountability, and even contemplation of payments for results. And, in terms of human resource management in the NPM context, schools saw the glorification of the hero leader. Peter Senge (2000) observed:

‘I have come to see our obsession with the hero-CEO as a type of cultural addiction. Faced with the practical needs for significant change, we opt for the hero-leader rather than eliciting and developing leadership capacity throughout the organization. A new hero-CEO arrives to pump new life into the organization’s suffering fortunes. Typically, today, the new leader cuts costs (and usually people) and boosts productivity and profit. But the improvements do not last.’

New Public Management facilitated the growth of the hero-leader, because in schools the principal was seen as being solely responsible for the school’s performance, and the accountability processes reinforced that tenuous algorithm. As a result, school decision making became less consensual, and performance management became both a carrot and a stick within a context where schools were judged by accountabalist standards on their competitiveness on the national testing scales, and League Tables.

Louis XIV is acknowledged as saying, “L'état, c'est moi.” I am the state, or the state is me, and to a degree the same now holds for school leaders, because these days school leaders can expect phone calls from parents or employers on weekends and school holidays. There is often no defined school time, or no personal-private time. And, at school in most cases the former hierarchical boundaries and positional respect have melted away, so the hero school leaders are seen as directly involved in solving a multitude of sins.

War Stories and Hardskills

Accompanying the move to the New Public Management model, and the change in language away from a people focus was the language and values of the hero leaders. As a result, the language of leadership in schools became preoccupied with accountability, crisis management, control, success, and conflict resolution. Examples can be seen in business where change managers were measured against the likes of Al Dunlap, who was also known as ‘Chainsaw Al’ (‘Mean business: How I save bad companies and make good companies great', 1996), with the generic ‘Snakes in Suits’ (Babiak & Hare, 2006) metaphor describing new hard-skilled management. Famously, Al Dunlap (1996, p. 39) warned of leadership fads:

‘A favorite today is consensus management… But consensus management doesn’t work; it’s a disaster that pushes its smiling, happy practitioners to less than their best solutions for their companies. To placate everybody, consensus managers sacrifice what’s important.’

War stories are experiential statements that are often traded in groups of school leaders, and they serve an educational purpose as well as a resource identification exercise. Merriam-Webster (n.d.) noted of the term war stories:

‘But today tellers of ‘war stories’ need not have experienced a literal battlefield. Around the middle of the 19th century, ‘war story’ took on a more figurative meaning, and nowadays such accounts can encompass challenges in the workplace, on the campaign trail, in sports, in one's travels… wherever difficulties need to be overcome.’

War stories, such as those Chainsaw Al recounts, tend to promote hard-skills, conflicts and disasters and leadership ratings are often influenced by such extreme experiences. Even selection panels want to know that the applicant can make hard decisions with hard skills. But in schools that are operating successfully at authenticated high levels, the last thing they need are ‘Snakes in a Suits’ who feel that the organisation needs to reflect their idiosyncratic hard-skills view of efficient operation. High levels of softskills are notoriously difficult to quantify, and then to be valued. For example, job applicants stating that they personally greet 53 families at the school gate every day are not going to be rated highly by selection panels in comparison to another claim of turning around a failing school in a Covid saturated environment. It is important for school leaders to consider the school situation and then measure a leader’s actions against that real situation, so that softskills can be seen as appropriate, and become valued.

Getting Better Results by Valuing Softskills

Kate Morgan (2022) recently reported for the BBC Worklife program that ‘In order to do your job effectively, you need hard skills: the technical know-how and subject-specific knowledge to fulfil your responsibilities. But in a forever-changed world of work, lesser-touted ‘soft skills’ may be just as important – if not even more crucial.’ With the increasing importance of developing work-based teams in organisations Morgan claimed that modern employers are now taking these softskills into account when establishing work teams.

What are softskills?

Softskills is a term that is used to describe the personal and inter-personal skills that are contrasted with the more identifiable ‘hardskills’. The term is ill-defined, but it is now being seen as an essential quality. A search of the literature demonstrates the scope of understanding of what can be described as a softskill. Phillips, Phillips and Ray (2020, p. 8) noted that:

- Hardskills are technical, profession specific, or job related (the ‘what’);

- Softskills are transferable, personal, and interpersonal related (the ‘how’).

Alison Doyle (2021) claimed that ‘Hard skills’ are teachable abilities or skill sets that are easy to quantify. Typically, you'll learn hard skills in the classroom, through books or other training materials, or on the job. And, soft skills, on the other hand, are subjective skills that are much harder to quantify.’ Also known as ‘people skills’ or ‘interpersonal skills,’ soft skills relate to the way you relate to and interact with other people. This dichotomy basically divides on the interpersonal, often intuitively personal characteristics that are placed against the formal, structural, professional aspects of leaders’ roles, and some skills are both hard and soft, depending on how they are done.

For example, a ‘hardskill’ may be to improve workers’ job motivation. The hard skill would be to negotiate rewards measured against productivity, and the soft skill would be to negotiate some empathetic reward that solves a worker’s family problem – “Yes you can attend your daughter’s school assembly!”.

Table 1 The Personal Qualities Identified as Softskills

| SOFTSKILL | Gates 2021 | Indeed 2021 | Fond 2019 | Tulgan in Phillips et al, 2020 |

| Emotional intelligence | X | Empathy |

Citizenship |

|

| Time management | X | X | ||

| Written communication | X | |||

| Creativity and innovation | X | X | ||

| Active listening | X | X | ||

| Goal setting | X | Self motivation | X |

Service |

| Adaptability | X | |||

| Mental agility | X | Decision making | ||

| Collaboration, teamwork | X | X | X | |

| Optimism | X | Positive attitude | ||

| Interpersonal communication | X | X | People skills | |

| Attention to detail | X | Personal responsibility | ||

| Critical thinking | X | Self-reflection | ||

| Decisiveness, decision making | X | X | X | |

| Patience | X | |||

| Transparency | X | |||

| Consistency & reliability | X | |||

| Trustworthiness | X | |||

| Reward, recognise employees | X | |||

| Willingness to change | X | |||

| Conflict resolution | X | |||

| Proactive learning | X |

Softskills: Growing Social-Emotional Learning

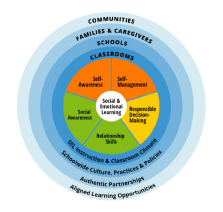

Social Emotional Learning (SEL), which is a necessary condition for social life is most effectively assimilated from social environments, and inter-personal interactions. The CASEL (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, 2020) Framework shows the inter-related nature of SEL.

Figure 1 CASEL’s Core Competencies

CASEL (2020) believes there are five core SEL competencies: 'The five broad, interrelated areas of competence are: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making.' And, they believe that these competencies, all of which are softskills, can be taught in classroom, schools, homes and communities, as can be seen in Figure 1. Acknowledging the CASEL Framework, Frey, Fisher and Smith (2022, p. 2) listed four teaching tasks for schools:

1 Teach skills and promote a classroom climate that fosters dispositions;

2 Work together at the school level to create a schoolwide culture that manifest the way these skills and dispositions are enacted…;

3 Partner with families…;

4 Coordinate with communities to create….

The point that we make is that the softskills are important and they can be taught about, and more importantly underwrite the schools’ and communities’ cultures.

Conclusions

Visitors to schools are often impressed with the physical aspects of what they can see in schools – the new Performing Arts Centre, the new computers, the winning sports teams, and the green rectangles on the My School site that adorn principals’ offices. These obvious factors are like bricks in a building foundation, but the mortar, or ‘mud’ as the bricklayers call it, is even more important because it gives the bricks a purpose, in a structural sense. The softskills are the mud that that holds the school structure and programs together, but the bricks and mortar are equally important.

In reality, it is wrong to think of hardskills and softskills as an unforgiving dichotomy, because they are not discrete entities, and importantly, the adjectives of ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ get in the way of understanding good leadership.

However, while we initially set out to advocate a reassessment of the balance between softskills and hardskills in school leadership, we realised that softskills and SEL are closely related and these skills underpin all interactions and cultural issues in a school. So, softskills can be grown in every school, and the ability to embed these softskills into the school culture and daily operations is a mark of strong leadership.

Thank you.

References

Babiak, P., & Hare, R.D. (2006). Snakes in suits: When psychopaths go to work. New York: Harper.

CASEL (2020). CASEL’s SEL framework. https://casel.org/casel-sel-framework-11-2020/

Doyle, A. (2021). Hard skills v. soft skills: What’s the difference? https://www.thebalancemoney.com/hard-skills-vs-soft-skills-2063780

Dunlap, A.J. (1996). Mean business: How I save bad companies and make good companies great. St Petersburg, FL: Mr Media Books.

Fond (2019, November 12). Qualities of a good manager: 13 soft skills you need. Fond Technologies. https://www.fond.co/blog/qualities-of-a-good-manager/

Frey,, N., Fisher, D., & Smth, D. (2022). The social-emotional learning playbook: A guide to student and teacher well-being. Corwin.

Gates, M. (2021, November 1). 10 soft skills every manager should have in 2022. Powertofly Blog. https://blog.powertofly.com/soft-skills-for-managers

Indeed Editorial team (2021, April 20). 9 soft skills for management. Indeed. https://www.indeed.com/career-advice/career-development/soft-skills-for-management

Merriam-Webster (n.d.). War story. https://www.merriam-webster.com>dictionary › war story

Morgan, K. (2022, July 28). 'Soft skills': The intangible qualities companies crave. BBC Worklife. https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20220727-soft-skills-the-intangible-qualities-companies-crave

Osborne, S.P., & McLaughlin, K. (2002). The New Public Management in Context. In K. McLaughlin, S.P. Osborne, & E. Ferlie, New Public Management: Current trends and future prospects. London: Routledge.

Phillips, P., Phillips, J.J., & Ray, P. (2020). Proving the value of softskills: Managing impact and calculating return on investment. Alexandria, VA: atd Press.

Senge, P. (2000). The leadership of profound change: The myth of the hero-CEO. SPC Ink. https://www.spcpress.com/pdf/other/Senge.pdf