Wellbeing Across the Educational Landscape - Article 2: Trauma-Responsive Educational Practices

To appreciate the necessity for trauma-responsive educational practices, we must first understand the prevalence and impact of trauma in our communities. We are then able to identify and implement strategies to support trauma-impacted students’ (and staff's);

● Psychological and physical safety

● Improved brain organisation and functioning

● Nervous system regulation

● Behavioural, learning and performance outcomes.

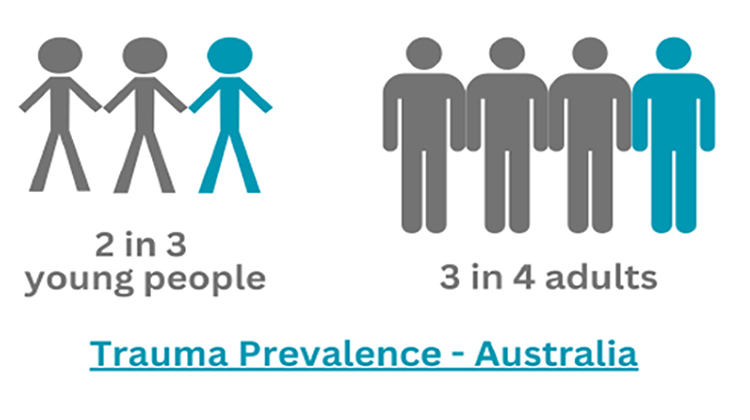

In Australia up to 66% of young people are exposed to at least one traumatic event by the age of 16, with 75% of adults having experienced a traumatic event at some time in their life. Globally the figures are slightly lower (60% and 70% respectively), with 30.5% of people worldwide experiencing at least 4 traumatic events.

Trauma can be any real, or perceived;

● Singular event that threatens serious injury or death

● Prolonged and repeated experiences of trauma, abuse or neglect

● Indirect exposure to a traumatic event (secondary or vicarious trauma), or

● Transmission to subsequent generations (intergenerational trauma).

Some people are more susceptible to trauma exposure, including those who are; homeless, young people in out-of-home care or under youth justice supervision, experiencing family and domestic violence, Indigenous peoples, LGBTIQA+, refugees, veterans, or workers in emergency services and armed forces.

The effects of trauma can be diverse, and unique to each person. Some people may experience little to no impact on their wellbeing or functioning, or even experience post-traumatic resilience. However, negative trauma responses can include;

● Temporary (immediate or delayed) effects

● Persistent effects due to;

○ Chronic (ongoing) trauma such as bullying, abuse and neglect

○ Complex trauma (repeated, or multiple, trauma events)

○ Unresolved trauma stuck in the body, or

○ Developmental trauma - when young people exposed to complex trauma experience widespread disruptions to their academic, social, and occupational functioning due to impacted cognitive, emotional, physiological, and relational capacities.

As highlighted in Article #1 of this series, trauma stress responses are often automatic subconscious nervous system activations, designed to regain safety and security. The survival parts of the brain are in control, and override the areas responsible for emotional control, connection, reasoning, and learning. Trauma responses will persist until an individual gains a felt sense of safety and returns to their Window of Tolerance, where they have adequate energy and resources to meet life’s demands.

Common temporary reactions to trauma, which tend to resolve without long-term consequences, include; agitation, physical arousal, exhaustion, confusion, sadness, worry, numbness, reduced emotional responses, nausea, dizziness, changes in sleep and appetite, withdrawal from daily activities, feelings of fear and grief.

Chronic, complex or unresolved trauma can cause the nervous system to get stuck on high alert, in order to deal with perceived dangers. Nervous systems may also get stuck in certain trauma stress responses, by overestimating the presence, intention and force of perceived threats. Individuals may also habitually rely on stress responses that were helpful in the past, but are unhelpful in current situations.

More persistent and severe trauma responses may include; mental distress or ill-health, anxiety, depression, dissociation, psychosis, personality disorders, self-harm and suicide-related behaviours, eating disorders, alcohol and substance misuse, disability, unemployment, reduced lifespan.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is experienced by 11% of people in Australia, 3.9% globally, and 15.3% among people exposed to violent conflict or war. PTSD significantly impacts daily functioning including cognition, concentration, mood, social engagement, arousal, emotional and behavioural regulation, avoidance of trauma reminders, and self-destructive behaviours.

Developmental trauma impacts neurobiological development, and could impair or disrupt the 7 domains of global functioning:

● Cognitive processes - executive functions including reflection, mental flexibility, problem-solving, and learning from future experiences interfere with attention, concentration, memory, learning, decision-making and interpersonal functioning

● Behavioural control - general inhibition, automatic behavioural responses to perceived threats, reckless and destructive behaviours

● Emotional regulation

● Attachment

● Biology

● Dissociation, and

● Self-concept.

Trauma-influenced worldviews may lead young people to develop complex stress-mediated adaptive behaviours. They are often diagnosed with ADHD, oppositional defiance disorder, conduct disorders, anxiety disorders, communication disorders, learning difficulties, autistic spectrum disorders. Multiple or long-lasting traumas when young may lead to complex PTSD (c-PTSD), characterised by disturbed emotional regulation, negative self-concept, and pervasive relational disturbances.

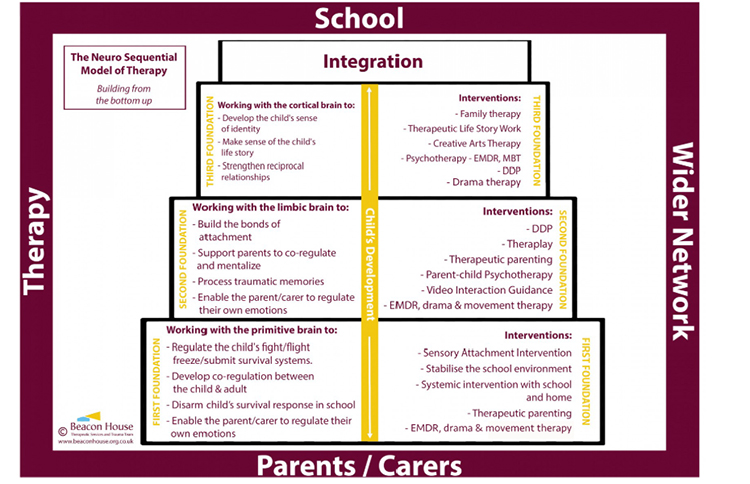

The Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics (NMT) identifies internal and external factors that impact neurobiological development. The NMT suggests that neurological losses caused by developmental trauma may be recovered to some degree, by supporting sequential brain development, organisation and functioning with specific interventions. These principles apply to ongoing trauma recovery, as well as discrete occurrences of distress and dysregulation. Please see below to find practical applications of NMT under “Trauma-informed educational practices”.

The Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics

Examples of progressive and universal capacity gains, due to supporting sequential brain development and organisation

The NMT can be applied alongside various educational practices to support trauma-affected students, which range from being trauma-aware to trauma-responsive;

● Trauma-aware

● Trauma-sensitive

● Trauma-informed

● Trauma-responsive.

Individual and organisational knowledge, skills, resources and process implementation develop over time, ideally progressing from being trauma-aware to trauma-responsive.

Trauma-aware

Trauma awareness begins with acknowledging the existence of trauma, understanding what it is and its effects for students, colleagues and people in your community. This includes being aware of trauma sensitivities or ‘triggers’ which may activate involuntary trauma stress responses. This is the first step in ensuring safe educational spaces and experiences for students and staff.

Trauma-aware educational practices;

● Trauma training for educational leaders and staff to support implementation of trauma-aware education and programs.

Trauma-sensitive

Trauma-sensitivity extends beyond acknowledging trauma, to understanding the need for different responses for trauma-affected individuals. Trauma-based knowledge and skills are developed, and incorporated into communications and interpersonal interactions. Processes and infrastructure, which support staff to recognise trauma and engage in trauma-responsive practices, are investigated.

Trauma-sensitive educational practices;

● Create an organisational culture of safety and empowerment for students, staff and community members.

● Acknowledge and support ‘at risk’ populations, and students who have experienced trauma.

● Inclusive practices, acknowledging that any student or colleague may have experienced trauma.

● Reduce sensory stimulation to avoid overwhelming trauma-impacted students.

● Awareness, and avoidance, of potential trauma triggers e.g. loud noises, bright lights, yelling, invading personal space.

● Establish familiar and predictable routines to help students feel safe (this can help reduce the stress hormones adrenaline and cortisol); visual schedules, verbal reminders, inform of schedule changes, discuss expectations, prepare students for activities that may elicit strong emotions

● Develop supportive relationships with students to increase a felt sense of safety (this can help increase feel-good hormones like oxytocin, endorphins, dopamine and serotonin).

● Non-judgement and non-shaming. “Behaviour is communication”, rather than non-compliance. Behaviour is communicating a need, and is possibly an involuntary trauma stress response. Ask the question ‘What happened to you?’ with curiosity and care, rather than taking the punitive and critical approach of ‘what is wrong with you?’.

● Appropriate strategies to manage behavioural difficulties, including when students engage in trauma stress responses. This involves supporting students’ self-efficacy regarding self-awareness and self-regulation.

● Implement practices such as encouraging open communication, setting clear boundaries, and prioritising well-being e.g. quiet spaces for when any students feel overwhelmed, counselling and other support services

Trauma-informed

A trauma-informed approach integrates trauma-based knowledge and skills into policies, procedures, and practices across the whole organisation. Included are intentions to avoid re-traumatisation, promote healing, foster resilience, respect diversity and uphold equity. Becoming trauma-informed is an ongoing process of organisational change.

Trauma-informed educational practices;

● Evaluate and revise educational policies, practices and programs (including those related to discipline and conflict resolution) to incorporate relationship-based collaborative frameworks. For example;

○ Implementing school-wide Social and Emotional Learning (SEL)

○ Prioritising inclusivity e.g. not removing students, school resources or experiences, for problematic behaviours

○ Reinforcing social support systems of trauma-affected individuals

● Uphold the professional and personal wellbeing of staff, including supports, supervision and reflective practice

● Universal trauma screening, with trauma-specific resources and support referrals offered to those in need.

***Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics

● Level 1 ~ Brainstem ~ Impulsivity, arousal, attention and regulation difficulties caused by brainstem disorganisation can be addressed through improving perceptions of safety with attuned responsive caregiving, coregulation, and self-regulation with safe, rhythmic and repetitive somatosensory activities (i.e. movement such as drumming, clapping, tapping, rocking, yogic breathing).

***Repetition is key for developing and strengthening new neural networks. These rhythmic activities can be briefly repeatedly throughout the day i.e. when students resume working at their desks after lunch or other activities.

***This repetition will also provide the stability and predictability necessary for trauma-affected students.

***Mix it up - engaging in various regulation strategies will meet the needs and learning styles of all students

***If students become dysregulated, try slowing the tempo of the activity or your voice - this co-regulation strategy will encourage their nervous systems to slow down and regulate

● Level 2 ~ Midbrain ~ Midbrain development requires more complex rhythmic movement and music, simple narrative experiences, and emotional and physical warmth

● Level 3 ~ Limbic System ~ More complex and whole-body movement, increasingly complex narrative exercises, co-regulation, and relationally-oriented activities including play and creative arts, support limbic development of interpersonal relational skills

● Level 4 ~ Cortical brain ~ Continued reciprocally supportive social interactions, more complex narrative experiences, and psychodynamic or cognitive-behavioural therapy, can support insight and verbal related cortical functioning.

Trauma-responsive

Trauma-responsiveness is a preventative and proactive approach to addressing trauma through an organisation’s values, language, environment and programs. Current research and the community’s specific trauma needs inform ongoing assessment, feedback and adaptability across the whole organisation

Trauma-responsive educational practices;

● Constructive and collaborative partnerships with local services, and carers of young people who are experiencing adverse effects of trauma

● Ongoing input from trauma survivors regarding the design and evaluation of support activities, policies and services

● Aligning all stakeholders to shared trauma-responsive values, language and practices.

Barrowford Primary School (East Lancashire, UK) is an excellent example of a trauma-responsive educational institution;

● Rachel Tomlinson, Headteacher, recognises the necessity to meet the needs of the whole child (physical, emotional and mental health), and their families, because behaviour is “communication, not compliance”

● Adapting organisationally to ensure a "good fit" for new students who are trauma-affected, and continued evaluation to ensure relevant support for existing students

● Acknowledgement of the unintentional harm caused by punitive systemic behavioural management practices

● Whole-school restorative practices approach to Relationship Management, rather than Behavioural Management

● Barrowford’s Relationship Management Policy outlines various supports for the school community

● Harmonious school environment, due to high levels of parental support and student engagement

● Equitable but flexible, needs-based access to curriculum and supportive resources

Barrowford have also implemented a Creative Empowerment Model - a teacher training package incorporating experiential learning, creative practices and group facilitation to support different learning styles and increased student engagement. Students use their 5 Power tools (Imagination, Voice, Movement, Mirroring and Rhythm) to improve focus, attention, engagement, autonomy, involvement in their learning, and learning outcomes. Students reflected feeling happier and more involved, and how dancing in the morning “warms our bodies up and gets our learning brains on”. Teachers also benefited from more collaborative and supportive intra-school connections.

Duty of Care

As highlighted by Rachel Tomlinson, schools may unintentionally cause harm through lack of trauma-responsiveness to trauma-affected individuals (students and staff).

All educational staff have a legal responsibility to protect young students from harm. All reasonable preventative measures should be taken "to reduce risk, create a safe environment and implement strategies to prevent bullying". For principals, this duty of care extends to staff.

As highlighted throughout this article series, trauma can have a significant impact on individuals' cognitive, emotional, social and physical capacities. And the first step in supporting all people, especially those who have experienced trauma, is safety, security and connection. Trauma-responsive educational practices are a critical component of this equation, as evidenced by research including;

● Whole-school SEL programs improving SEL skills and pro-social behaviours, and decreasing conduct problems and emotional distress

● Teacher-delivered programs that can be more effective than programs delivered by other school staff, including mental health professionals

● An after-school program that supported at-risk African refugee children to develop healthy coping skills, and decrease distress and PTSD symptoms

● Students with learning difficulties experiencing improved;

○ academic results - empowerment to seek support, improved access to curriculum, school engagement

○ understanding of success - improved competency and self-efficacy, redefining what success means at school

○ relationships - increased trust with adults, connection with peers and sense of belonging at school

○ teacher outcomes - improved perceptions of students, support of the whole child

● An Australian special school reporting high staff satisfaction, improved student wellbeing and attendance, and progress towards learning goals

● Australian educators reporting trauma training to result in improved;

○ perceptions of student behaviour, adaptations to behaviour management practices, trust and respect in school climate, the centrality of leadership to effect change

○ understanding of the impact of intergenerational trauma and multi-systemic influences on student behaviour difficulties, self-efficacy to provide culturally safe learning environments and build relationships with First Nations students.

In closing, some considerations;

● As an educational professional,where do you sit on the spectrum from trauma-awareness to trauma-responsiveness

● From the suggestions above, what are some strategies that you could personally implement to support students in your institution that may be trauma-affected? Which measures may help you better fulfil your duty of care for students' psychological and physical safety?

● Where does your educational institution sit on the spectrum from trauma-awareness to trauma-responsiveness?

● What strategies could your institution implement to increasingly support trauma-affected students, staff and community members? Are any measures required for your institution to more adequately fulfil its duty of care to students and staff? How can you support the identification and implementation of these strategies?

Stay tuned for Article #3 in this series; “Wellbeing Considerations to Support Young Students' Learning”

With best wishes,

Kim

(The information in this article is not intended as medical advice. For persistent stress or specific support, professional healthcare is advised.)

Resources

- Part 1 - Interview with Rachel Tomlinson, Headteacher, Barrowford Primary School, UK - facilitating ‘whole child’ support by embedding whole-school consequence-based restorative practices, conflict resolution and relationship management

- Part 2 - Interview with Rachel Tomlinson, Headteacher, Barrowford Primary School, UK- “front-loading” safety and support for improved learning outcomes, with trauma-responsive teams and ‘nurture’ spaces, while managing top-down pressures (budget, academic assessments)

- Relationship Management Policy - Barrowford Primary School

- Creative Empowerment Model - Barrowford Primary School

- National Guidelines for Trauma-Aware Education (Australia)

- Trauma-informed practice in schools: An explainer - NSW Department of Education

- Trauma-Skilled Schools Model - The National Dropout Prevention Center (New York)

- Legal duty of Care (Educational staff - Victoria, Australia)

Kim Vanderwiel has a background in clinical research, counselling, mindfulness and meditation, and is the founder and CEO of the Practical Wellbeing Institute. Kim has supported the wellbeing of young people and adults with different identities, needs and experiences, including; mental health challenges, trauma, neurodiversity, learning difficulties, LGBTQIA+, and multiculturalism. Kim is particularly passionate about supporting post-traumatic growth, and flourishing.